Bridging the Gap between Surveyors and the Geo-Spatial Society

by Hartmut Müller, Germany

Hartmut Müller

1)

The paper was presented in a joint FIG/ISPRS session at the ISPRS

Congress July 2016 in Prague. The author discusses the role of surveyors

today in a complex and technologic advanced world and the requirements

of the surveyor of tomorrow.

KEY WORDS: Geospatial Information, Information Technology,

Management, Surveyor, Geo-data Manager

ABSTRACT

For many years FIG, the International Association of Surveyors, has

been trying to bridge the gap between surveyors and the geospatial

society as a whole, with the geospatial industries in particular.

Traditionally the surveying profession contributed to the good of

society by creating and maintaining highly precise and accurate

geospatial data bases, based on an in-depth knowledge of spatial

reference frameworks. Furthermore in many countries surveyors may be

entitled to make decisions about land divisions and boundaries. By

managing information spatially surveyors today develop into the role of

geo-data managers, the longer the more. Job assignments in this context

include data entry management, data and process quality management,

design of formal and informal systems, information management,

consultancy, land management, all that in close cooperation with many

different stakeholders. Future tasks will include the integration of

geospatial information into e-government and e-commerce systems. The

list of professional tasks underpins the capabilities of surveyors to

contribute to a high quality geospatial data and information management.

In that way modern surveyors support the needs of a geo-spatial society.

The paper discusses several approaches to define the role of the

surveyor within the modern geospatial society.

1. INTRODUCTION

Surveying is a profession with a long history. Since ancient times

surveyors were involved in measuring and depicting the earth’s surface

with the natural, built and planned environments. Driven by the advances

of technologies including computing, communications and geospatial data

processing, the recent decades have shown increased demand and

importance on accurate, timely and user-friendly geospatial information

(Fosburgh, 2011, see also Seedat, 2014). As a result, the surveyor’s

role today includes communication with various stakeholders including

engineers, architects, planners, local government, landowners, utility

service providers and others. The surveyor’s new function has

transformed to that of geo-data manager, creating, verifying or

modifying digital data sources and design models of various kind.

Surveyors have to play an active part in GIS activities, such as

creating, filling and maintaining a GIS, and using it as a tool to

manage the natural and built environment as well as the cadastre. The

surveyor’s activities in GIS data collection are measurements, but also

collection and management of attributes about the elements they

geo-locate.

Most likely technology will play an even greater role in the future.

Field systems can be coupled with mobile phone and Internet access,

cloud computing and web-based geodatabases. In that way information and

techniques can be combined to an extent never before thought.

Traditionally, surveyors are well educated in terms of theory,

mathematics, principles of redundancy and quality assurance. The

opportunity for the surveyor to provide services that enable best

practices in data collection and quality assurance is still present

today. More than that, the deeper understanding of processes is even

more important in times where the surveying equipment has become so

user-friendly that the technology in most cases can be used by

non-surveyors. The ability to plan with a GIS and to use it to

understand ongoing processes is a huge opportunity for a geo-data

manager.

The surveyor of the future is able to extract new information and

knowledge from existing datasets and to provide it to land managers. The

society insists on speedier data collection and generation of useful

information. Therefore, it becomes imperative to use analysis tools for

managing, verifying and interpreting vast data volumes, data collection

for populating and updating the GIS, quality assurance and data

management and analysis. Communicating the information to the users will

be another key challenge. Surveyors should be prepared to present

information using a variety of media including static and dynamic

visualizations.

The surveyor of the future must demonstrate a broad set of

multidisciplinary skills. He or she must have the skills to navigate

various cultural and technical barriers as well as to communicate across

different knowledge areas, disciplines and customary local processes.

The world today has evolved from data collection into geo-data

management and information and knowledge extraction. Individual

surveyors, and the societies they belong to, must collaborate with

academia, government and industry to achieve common goals and benefits.

Fosburgh, 2011 states that surveyors are the geo-data managers of the

future--and that tomorrow’s professionals are prepared for the challenge

through education, training and professional development. In the

following sections the positions of FIG, the International Federation of

Surveyors and of DVW, German Society of Geodesy, Geoinformation and Land

Management in this debate will be reported.

2. FIG DEFINITION OF THE FUNCTIONS OF THE SURVEYOR

FIG is a federation of national associations and represents the

surveying disciplines. Its aim is to ensure that the disciplines of

surveying and all who practise them meet the needs of the markets and

communities that they serve. It realises its aim to ensure that the

disciplines of surveying meet the needs of markets and communities by

promoting the practice of the profession and encouraging the development

of professional standards. In 2004, the FIG General Assembly adopted its

own definition of the functions of the surveyor (FIG, 2004).

2.1 The official FIG definition

2.1.1 Executive summary: A surveyor is a

professional person with the academic qualifications and technical

expertise to conduct one, or more, of the following activities;

- to determine, measure and represent land, three-dimensional objects,

point-fields and trajectories;

- to assemble and interpret land and geographically related information,

- to use that information for the planning and efficient administration

of the land, the sea and any structures thereon; and,

- to conduct research into the above practices and to develop them.

2.1.2 Detailed

functions: The surveyor’s professional tasks may involve one or more of

the following activities which may occur either on, above or below the

surface of the land or the sea and may be carried out in association

with other professionals.

- The determination of the size and shape of the earth and the

measurement of all data needed to define the size, position, shape and

contour of any part of the earth and monitoring any change therein.

- The positioning of objects in space and time as well as the

positioning and monitoring of physical features, structures and

engineering works on, above or below the surface of the earth.

- The development, testing and calibration of sensors, instruments and

systems for the above-mentioned purposes and for other surveying

purposes.

- The acquisition and use of spatial information from close range,

aerial and satellite imagery and the automation of these processes.

- The determination of the position of the boundaries of public or

private land, including national and international boundaries, and the

registration of those lands with the appropriate authorities.

- The design, establishment and administration of geographic

information systems (GIS) and the collection, storage, analysis,

management, display and dissemination of data.

- The analysis, interpretation and integration of spatial objects and

phenomena in GIS, including the visualisation and communication of such

data in maps, models and mobile digital devices.

- The study of the natural and social environment, the measurement of

land and marine resources and the use of such data in the planning of

development in urban, rural and regional areas.

- The planning, development and redevelopment of property, whether

urban or rural and whether land or buildings.

- The assessment of value and the management of property, whether

urban or rural and whether land or buildings.

- The planning, measurement and management of construction works,

including the estimation of costs.

In the application of the foregoing activities surveyors take into

account the relevant legal, economic, environmental and social aspects

affecting each project.

2.2 Recent developments in FIG

The definition reported in Section 2.1 reflects to a great extent the

traditional professional field of surveyors. At the FIG Working Week in

Rome, Italy, (May 6-10, 2012) FIG started to broaden its view towards a

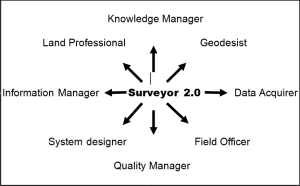

wider definition, described by the term ‘Surveyor 2.0’ (Schennach et

al., 2012). Teo CheeHai, past president of FIG, has noticed that ‘the

role of the surveyor is evolving from a professional who used to be

viewed as a “measurer” to a professional who measures, models, and

manages’.

ACSM, 2012 notes rapid technological changes are taking place in a

challenging economic and political landscape. Online and mobile

services, such as online maps and smartphone apps, are stimulating an

increasing interest and use of geospatial information. Citizen-centric

service delivery is crucial. In this interview the president argues,

that surveyors ‘will be required to embrace open standards; be

inclusive, learn to incorporate volunteered information; ensure

interoperability of systems, institutions and legislation; have a

culture of collaboration and sharing to avoid duplication; develop

enabling platforms in order to deliver knowledge derived from data of

different scales and origins in the form of “actionable” information’.

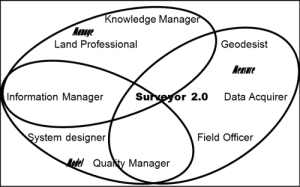

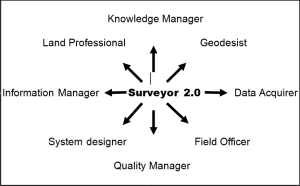

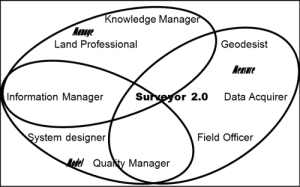

In an ongoing discussion FIG now promotes the ‘Surveyor 2.0 model’ (Fig.

1).

|

|

Figure 1. The Surveyor 2.0 Model,

adapted from G. Schennach et al. (2012)

Here, the surveyor is described in the triad Manage-Model-Measure. Such

a definition seems to largely overlap with the definition of a geo-data

manager (see the following section).

3. THE PROFILE OF A GEO-DATA MANAGER

Recently, in an ongoing process the Working Group ‘Geoinformation and

Geo-data Management’ of the German DVW, Society for Geodesy,

Geoinformation and Land Management worked on the definition of a

geo-data manager’s functions. In the following sections some

intermediate results of the work will be reported.

3.1 The framework of geo-data management

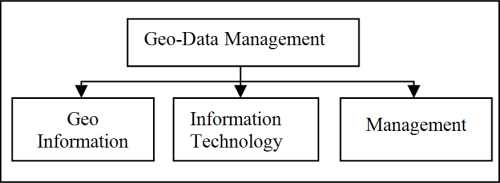

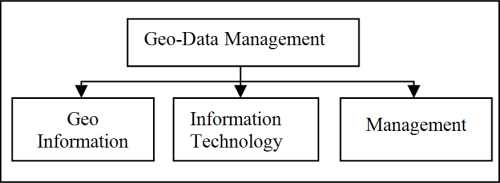

Geo-data management is a cross-cutting task of Geodesy and

Geoinformatics comprising three core areas of expertise (Fig. 2):

Figure 2. The triad of Geo-data Management,

(German DVW Working Group, 2016, unpublished)

1. Geoinformation; in particular application-specific recording, quality

assurance, analysis and presentation of spatial objects based on the

geodetic spatial reference of position, height and gravity (Geo skills),

2. Information technology; in particular technology of data and systems,

design and implementation of technical solutions, development of

service-oriented architectures and systems, modeling, coding and

automation of data exploration, by methods of information and

communication technology (IT skills)

3. Management; in particular strategic development, structuring,

coordination and control of processes, by communication with all

involved parties (management skills)

3.2 The individual profile of a geo-data manager

Depending on the individual field of work a geo-data manager may face a

considerable range of required skills in the three core areas of

expertise Geoinformation, Information technology, Management. The full

requirements profile of a geo-data manager comprises the following

components

3.2.1 Professional

skills: the following section describes the full list of currently

identified professional skills of a geo-data Manager.

- Establishment of a framework for the comprehensive use of geospatial

data. The geo-data manager coordinates development and operation of

spatial data infrastructures to provide spatial data from different

sources by interoperable spatial data services. He or she moderates the

interests of providers and users and develops the legal, professional,

technical and organizational framework for the comprehensive use of

spatial data. He or she develops application-driven specifications for

data provision via standard based services. He or she monitors

compliance with the specifications to ensure the multidisciplinary

usability of spatial data (interoperability).

- Identification of spatial data needs, as-is analysis and data

collection. The geo-data Manager identifies and analyzes the user

requirements (internal vs. external users) in the context of specific

applications. He or she gets an overview of available data (inventory

analysis of in-house offers against third party offers) and evaluates

the potential benefit of spatial data sets for specific application

areas, in cooperation with experts from other disciplines. He or she

procures appropriate spatial data obtained by third parties and

clarifies access, usage and pricing conditions.

- Data processing, administration, management and updating. The geo-data

Manager collects existing data, transforms them into consistent data

formats, integrates them geometrically and semantically into a

Geographic Information System (GIS), prepares them to meet individual

professional requirements, updates and maintains them. He or she

accomplishes these tasks within an established framework and provides

the necessary transformation rules, exchange formats and meta data.

- Application-specific exploration of spatial data, process integration

and information management. By analyzing and redesigning processes and

by developing an adapted role model the geo-data manager supports the

integration of data products into an existing environment of

administrative and business processes. To generate new information he or

she designs and implements automated analysis of combinations of spatial

data from different sources (exploration of Big Geo-Data). He or she

prepares the results clearly. He or she is involved in collaboration

processes with other disciplines to interpret spatial data

appropriately. He or she ensures that the necessary information is

generated in a user-centric form.

- Design of new data products. On the basis of needs assessment and

inventory analysis the geo-data manager designs new data products for

specific applications while also taking into account future demands of

stakeholders. To achieve that, he or she creates conceptual application

schemes in communication with other specialists and IT experts data.

Following his or her professional expertise the coding for the data

transfer in appropriate data formats will be performed (external

schema). He or she provides support for the implementation of the data

management policy

- Development of production methods. The geo-data manager identifies

appropriate methods for the geodetic collection of the product data

(initial recording vs. updating, such as terrestrial surveying, remote

sensing, crowdsourcing, mobile mapping) and adapts them to the technical

requirements. He or she coordinates the interaction of different

partners to create novel data products. He or she develops quality

assurance procedures to guarantee for the long-term professional and

technical product quality which meets the user requirements.

- Definition of the general data production environment, particularly

for marketing and sales activities. The geo-data manager determines the

framework for spatial data marketing and sales. He or she determines

product names and product specifications, takes into consideration any

access restrictions (copyright, security, privacy) and other obligations

determined by legal regulations. He or she defines the usage and payment

terms, targeted markets, distribution channels, product availability,

performance and provided capacity of the data production process. He or

she creates the documentation of product specification, for in house use

and for publication in metadata catalogs provided within spatial data

infrastructures.

- Implementation and operation of an IT infrastructure to manage spatial

data (GeoIT infrastructure). The geo-data manager identifies data

volumes, access rights, facades and role models for the use of spatial

data in an organization. Following the trends of the mainstream IT he or

she designs a standards based architecture of an appropriate GeoIT

infrastructure. The design of such architecture includes the system

design of network, servers, database management system, application

technology, referring to modern IT concepts (SOA, ROA, etc.) including

operation and safety concepts (ITSM). He or she makes decisions on the

necessary components of the GeoIT infrastructure, such as GIS, software

/ hardware and other technical core components (geo portals, geo

catalogues, etc.).

- Design and development of services and applications. Following the

identified and adopted user requirements the geo-data manager develops

spatial data processing services to facilitate the implementation of

user-specific applications (desktop, web, mobile) such as specialized

geographic information systems vs. mainstream e-government applications

and other procedures.

- Quality management and quality control. The geo-data manager designs

and implements the user oriented framework for quality assurance of the

spatial data and of the derived products. He installs mechanisms to

monitor the entire process chain in order to ensure the spatial data

product quality.

- Basic, advanced and further training.

The geo-data manager provides basic, advanced and further user training.

3.2.2 Methodological and social skills: the

following section describes the most important identified methodological

and social skills of a geo-data Manager

1 Project management. The geo-data manager is involved in award

procedures, support, monitoring, controlling, resource management

(human, technical, financial), process documentation, reporting,

profitability analysis, decision management, and operational management

of spatial data projects and products.

2 Coordination. The geo-data manager coordinates and controls all

spatial data related processes in cooperation with all stakeholders. He

or she is the link between the technical and administrative management

levels. He or she moderates and supports the cooperation of different

stakeholders and ensures transparency in the project consortium

(information sharing).

3 Moderation. The geo-data manager moderates complex processes in a

highly interdisciplinary context. Fast-moving developments in the

digital world continuously generate processes of change. Different

understanding of the same topics across different professional

disciplines has to be considered. Reservations with regard to Geo-IT

infrastructures are still present. In this environment the geo-data

manager has to be a conflict manager who has pronounced negotiation

skills.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In the previous sections it was shown in which ways today’s surveyors

can take action for the benefit of a modern geospatial society. Job

assignments in this context include technical tasks such as data entry

management of highly heterogeneous spatial data created by classical

surveying activities, mobile mapping, aerial and satellite imagery,

crowdsourcing activities, and others; information management, consisting

of data integration and transformation, of data integration from

different sources, general IT, web technologies; quality management,

including responsibility for the accuracy of attributes and

relationships of data, for accuracy assessment, for completeness and

reliability of data, for certification; system design of formal and

informal systems for security of land tenure, for creation and

maintenance of code lists, for spatial data infrastructures, for 2D and

3D data management, workflows, business processes. In such a highly

interdisciplinary working environment non-technical skills are required

for interpersonal communication, including responsibility for

participation management, handling of appeal procedures, and conflict

resolution. Consultancy for urban and rural development, reorganization,

real estate issues, spatial planning may be further components of the

professional work. Future tasks include the integration of geospatial

information into e-government and e-commerce systems. Surveyors have the

potential to perform high quality geospatial data and information

management. If the surveying profession takes the plunge into the new

fields the gap between surveyors and the geospatial society can be

closed.

Acknowledgements

Decisive contributions of the members of the German Working Group André

Caffier, Dieter Heß, Martin Scheu, Markus Seifert, Robert Seuß to this

work are well acknowledged.

References

- Schennach, G., Lemmen, C., Villikka, M., 2012.

Be part of the solution,

not the problem! FIG Working Week, Rome, Italy. GIM International, July

2012, pp 33-35.

(10 May 2016).

- FIG, 2004.

FIG Definition of the functions of the surveyor

(10 May

2016).

- ACSM, 2012. FIG looks to surveyor 2.0, ACSM Bulletin June 2012, pp

31-32. 10 May

2016).

- Sass, J., 2012.

The surveyor’s role as geo-data manager, Machine Control

Magazine, Vol. 2 No. 3, 2012, Spatial Media, pp 45-47, (10 May 2016).

- Seedat, M., 2014.

The surveyor’s role as geo-data manager,

(10 May 2016)

- Fosburgh, B., 2011.

The evolution of the geo-data Manager,

(10 May 2016).

Contact

Hartmut Müller

Mainz University of Applied Sciences,

Institute for Spatial Information and Surveying Technology (i3mainz),

Lucy-Hillebrand-Str. 2,

D-55128 Mainz, Germany

[email protected]

|