Article of the Month -

July 2009

|

Facing the Global Agenda – Focus on Land Governance

Prof. Stig ENEMARK,

FIG President,

Aalborg University, Denmark

This article in .pdf-format (13

pages and 351 KB)

This article in .pdf-format (13

pages and 351 KB)

1) This paper is based on the

keynote presentation that Prof. Stig Enemark, FIG President gave at the

FIG Working Week in Eilat, Israel, 3-8 May 2009.

Key words: surveyors, land governance, Millennium Development

Goals, spatially enabled government.

SUMMARY

“Do surveyors have a role to play in the global agenda?” - from a FIG

point of view the answer to this question is clearly a “Yes”! Simply, no

development will take place without having a spatial dimension, and no

development will happen without the footprint of surveyors – the land

professionals.

There is a big swing that could be named “From Measurement to

Management”. This paper presents the changing role of the surveyors and

their commitment to the global agenda in terms of sound Land Governance

in support of the Millennium Development Goals.

1. THE GLOBAL AGENDA

The eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) form a blueprint agreed

to by all the world’s countries and the world’s leading development

institutions. The first seven goals are mutually reinforcing and are

directed at reducing poverty in all its forms. The last goal - global

partnership for development - is about the means to achieve the first

seven. These goals are now placed at the heart of the global agenda. To

track the progress in achieving the MDGs a framework of targets and

indicators is developed. This framework includes 18 targets and 48

indicators enabling the ongoing monitoring of the progress that is

reported on annually (UN, 2000).

“Do surveyors have a role to play in the global agenda?” -

from a FIG point of view the answer to this question is clearly a “Yes”!

The surveyors play a key role in supporting an efficient land market and

also effective land-use management. These functions underpin development

and innovation and form a kind of “backbone” in society that supports

social justice, economic growth, and environmental sustainability.

Simply, no development will take place without having a spatial

dimension, and no development will happen without the footprint of

surveyors – the land professionals.

Figure 1. The Eight Millennium Development Goals

The MDGs represent a wider concept or a vision for the future, where

the contribution of the global surveying community is central and vital.

This relates to the areas of providing the relevant geographic

information in terms of mapping and databases of the built and natural

environment, and also providing secure tenure systems, systems for land

valuation, land use management and land development. These aspects are

all key components within the MDGs.

In a global perspective the areas of surveying and land

administration are basically about people, politics, and

places. It is about people in terms human rights,

engagement and dignity; it is about politics in terms of land

policies and good government; and it is about places in terms of

shelter, land and natural resources.

Contributing to the Global agenda is about “flying high”. But the

idea is also to better understand the very key role that the surveying

profession play in underpinning sustainable development at national and

local level. This is about the daily work of the surveyors in meeting

the needs of the clients – it is about “keeping the feet on the ground”.

In facing the global agenda the role of FIG – the global surveying

community - is threefold: (i) to explain the role of the surveying

profession and the surveying disciplines in terms of their contribution

to the MDGs. Such statements should also make the importance of the

surveying profession disciplines better understood in a wider political

context; (ii) to develop and disseminate knowledge, policies and methods

towards achieving and implementing the MDGs - a number of FIG

publications have already made significant contributions in this regard;

and (iii) to work closely with the UN agencies and the World Bank in

contributing to the implementation of the MDGs.

An outcome of these efforts relates to cooperation with UN-Habitat in

developing a model for providing secure social tenure for the poorest

(Augustinus et.al. 2006). Another outcome is the recent joint FIG/World

Bank conference held in March 2009 focusing on “Land Governance in

Support of the MDGs – Facing the New Challenges”, see

http://www.fig.net/news/news_2009/fig_wb_march_2009.htm.

2. FROM MEASUREMENT TO MANAGEMENT

“Is the role of the surveyors changing?” – in a global perspective

the answer will be “Yes”! There is a big swing that could be entitled

“From Measurement to Management”. This does not imply that measurement

is no longer a relevant discipline to surveying. The change is mainly in

response to technology development. Collection of data is now easier,

while assessment, interpretation and management of data still require

highly skilled professionals. The role is changing into managing the

measurements. There is wisdom in the saying that “All good coordination

begins with good coordinates” and the surveyors are the key providers.

In the more technical and natural science area of surveying this move

can be illustrated by the evolution from the concept of Geodetic Datums

to Positioning Infrastructures. A geodetic datum is a (multi level)

geodetic reference framework describing positions in three dimensions.

It supports the traditional functions of surveying and mapping and

underpins all of what we now call geo-spatial information. The concept

of a Positioning Infrastructure is based on Global Navigation Satellite

Systems (GNSS) such as GPS and extends to the ground infrastructure used

to improve the accuracy and reliability of GNSS positioning for users.

It widens the functions to enable the monitoring of global processes

such as those associated with climate change and disaster risk

management and also real time positioning for e.g. agricultural farming

purposes (Higgins, 2009).

The concept of a modern Positioning Infrastructure (combining

satellites and reference stations on the ground) still supports the

activities traditionally associated with a geodetic datum but extends

toward much broader roles on the global scale. It can be argued that

GNSS could be considered one of the only true global infrastructures in

that the base level of quality and accessibility is constant across the

globe. Such a Positioning Infrastructure moves the focus from

measurement of framework points to management of the data received from

the positioning system.

The change from measurement to management also means that surveyors

increasingly contribute to building sustainable societies as experts in

managing land and properties. As mentioned above, the surveyors play a

key role in supporting an efficient land market and also effective

land-use management that underpin development and innovation for social

justice, economic growth, and environmental sustainability.

3. LAND GOVERNANCE

Arguably sound land governance is the key to achieve sustainable

development and to support the global agenda set by adoption of the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

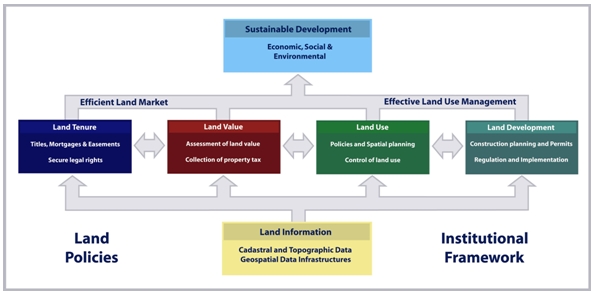

Land governance is about the policies, processes and institutions by

which land, property and natural resources are managed. This includes

decisions on access to land, land rights, land use, and land

development. Land governance is basically about determining and

implementing sustainable land policies. Such a global perspective for

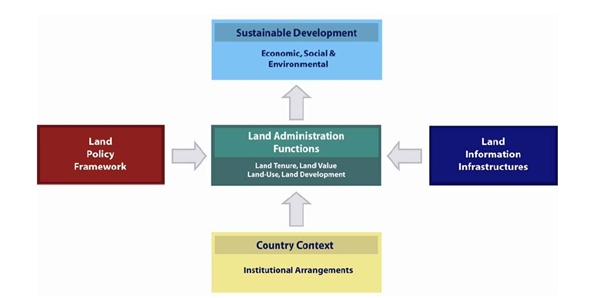

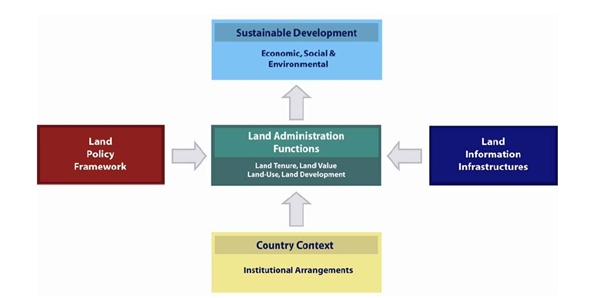

Land Governance or Land Management is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. A Global Land Management Perspective (Enemark, 2004).

Land governance and management covers all activities associated with

the management of land and natural resources that are required to fulfil

political and social objectives and achieve sustainable development.

Land management requires inter-disciplinary skills that include

technical, natural, and social sciences. The operational component of

the land management concept is the range of land administration

functions that include the areas of land tenure (securing and

transferring rights in land and natural resources); land value

(valuation and taxation of land and properties); land use (planning and

control of the use of land and natural resources); and land development

(implementing utilities, infrastructure, construction planning, and

schemes for renewal and change of existing land use).

Land administration systems (LAS) are the basis for conceptualizing

rights, restrictions and responsibilities. Property rights are normally

concerned with ownership and tenure whereas restrictions usually control

use and activities on land. Responsibilities relate more to a social,

ethical commitment or attitude to environmental sustainability and good

husbandry. In more generic terms, land administration is about managing

the relations between people, policies and places in support of

sustainability and the global agenda set by the MDGs.

3.1 Property Rights

In the Western cultures it would be hard to imagine a society without

having property rights as a basic driver for development and economic

growth. Property is not only an economic asset. Secure property rights

provide a sense of identity and belonging that goes far beyond and

underpins the values of democracy and human freedom. Historically,

however, land rights evolved to give incentives for maintaining soil

fertility, making land-related investments, and managing natural

resources sustainably. Therefore, property rights are normally managed

well in modern economies. The main rights are ownership and long term

leasehold. These rights are typically managed through the cadastral/land

registration systems developed over centuries. Other rights such as

easements and mortgage are often included in the registration systems.

The formalized western land registration systems are basically

concerned with identification of legal rights in support of an efficient

land market, while the systems do not adequately address the more

informal and indigenous rights to land that is found especially in

developing countries where tenures are predominantly social rather than

legal. Therefore, traditional cadastral systems can not adequately

supply security of tenure to the vast majority of the low income groups

and/or deal quickly enough with the scale of urban problems. A new and

innovative approach is found in the continuum of land rights (including

perceived tenure, customary, occupancy, adverse possession, group

tenure, leases, freehold) where the range of possible forms of tenure is

considered as a continuum from informal towards more formal land rights

and where each step in the process of securing the tenure can be

formalised (UN-Habitat, 2008).

3.2 Property Restrictions

Land-use planning and restrictions are becoming increasingly

important as a means to ensure effective management of land-use, provide

infrastructure and services, protect and improve the urban and rural

environment, prevent pollution, and pursue sustainable development.

Planning and regulation of land activities cross-cut tenures and the

land rights they support. How these intersect is best explained by

describing two conflicting points of view – the free market approach and

the central planning approach.

The free market approach argues that land owners should be obligated

to no one and should have complete domain over their land. In this

extreme position, the government opportunity to take land (eminent

domain), or restrict its use (by planning systems), or even regulate how

it is used (building controls) should be non-existent or highly limited.

The central planning approach argues that the role of a democratic

government includes planning and regulating land systematically for

public good purposes. Regulated planning is theoretically separated from

taking private land with compensation and using it for public purposes.

In these jurisdictions the historical assumption that a land owner could

do anything than was not expressly forbidden by planning regulations

changed into the different principle that land owners could do only what

was expressly allowed, everything else being forbidden.

The tension between these two points of view is especially felt by

nations seeking economic security. The question however is how to

balance owners’ rights with the necessity and capacity of the government

to regulate land use and development for the best of the society. The

answer to this is found in a country’s land policy which should set a

reasonable balance between the ability of land owners to manage their

land and the ability of the government to provide services and regulate

growth for sustainable development. This balance is a basis for

achieving sustainability and attaining the MDGs.

Informal development may occur in various forms such as squatting

where vacant state-owned or private land is occupied and used illegally

for housing or any construction works without having formal permission

from the planning or building authorities. Such illegal development

could be significantly reduced through government interventions

supported by the citizens. Underpinning this intervention is the concept

of integrated land-use management as a fundamental means to support

sustainable development, and at the same time, prevent and legalise

informal development (Enemark and McLaren, 2008).

3.3 Property Responsibilities

Property responsibilities are culturally based and relate to a more

social, ethical commitment or attitude to environmental sustainability

and good husbandry. Individuals and other actors are supposed to treat

land and property in a way that conform to cultural traditions and ways

of good ethical behaviour. This relates to what is accepted both legally

and socially. Therefore, the systems for managing the use of land vary

throughout the world according to historical development and cultural

traditions. More generally, the human kind to land relationship is to

some extent determined by the cultural and administrative development of

the country or jurisdiction.

Social responsibilities of land owners have a long heritage in

Europe. In Germany, for example, the Constitution is insisting on the

land owner’s social role. In general, Europe is taking a comprehensive

and holistic approach to land management by building integrated

information and administration systems. Other regions in the world such

as Australia creates separate commodities out of land, using the concept

of “unbundling land rights”, and is then adapting the land

administration systems to accommodate this trading of rights without any

national approach.

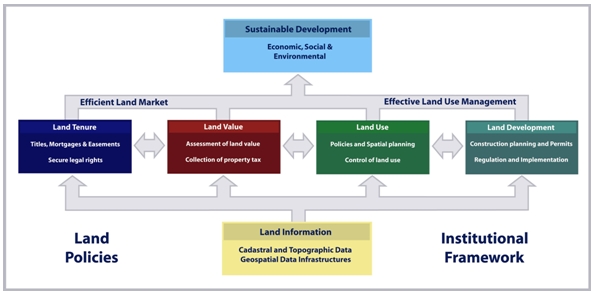

4. THE LAND MANAGEMENT PARADIGM

Land management underpins distribution and management of a key asset

of any society namely its land. For western democracies, with their

highly geared economies, land management is a key activity of both

government and the private sector. Land management, and especially the

central land administration component, aim to deliver efficient land

markets and effective management of the use of land in support of

economic, social, and environmental sustainability.

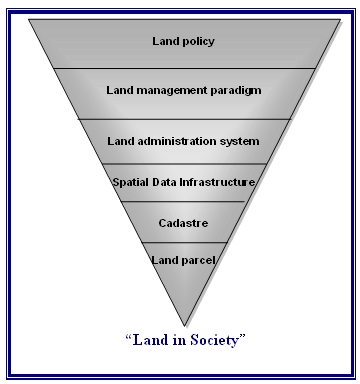

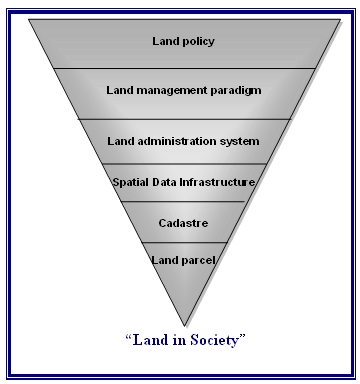

The land management paradigm as illustration in figure 3 below allows

everyone to understand the role of the land administration functions

(land tenure, land value, land use, and land development) and how land

administration institutions relate to the historical circumstances of a

country and its policy decisions. Importantly, the paradigm provides a

framework to facilitate the processes of integrating new needs into

traditionally organised systems without disturbing the fundamental

security these systems provide.

Figure 3. The land management paradigm (Enemark, 2004)

Sound land management requires operational processes to implement

land policies in comprehensive and sustainable ways. Many countries,

however, tend to separate land tenure rights from land use

opportunities, undermining their capacity to link planning and land use

controls with land values and the operation of the land market. These

problems are often compounded by poor administrative and management

procedures that fail to deliver required services. Investment in new

technology will only go a small way towards solving a much deeper

problem: the failure to treat land and its resources as a coherent

whole.

4.1 Hierarchy of land issues

The response to change pressures in any particular jurisdiction will

depend on how local leaders understand the vision. While the larger

theoretical framework described above is futuristic for many countries,

they must still design their land administration systems around the land

management paradigm. A simple entry point showing how to do this uses a

hierarchy of land issues in figure 4 showing how the concepts involved

in the paradigm fit together in a hierarchical manner ranging from land

policies to the land parcel.

Figure 4. Hierarchy of land issues

Land policy determines values, objectives and the legal

regulatory framework for management of a society’s major asset, its

land.

The land management paradigm applies to LAS design to drive an

holistic approach to the LAS, and forces its processes to contribute to

sustainable development. The paradigm allows LAS to assist land

management generally. Land management activities include the core land

administration functions: land tenure, value, use and development, and

encompass all activities associated with the management of land and

natural resources that are required to achieve sustainable development.

The land administration system provides the infrastructure for

implementation of land policies and land management strategies, and

underpins the operation of efficient land markets and effective land use

management. The cadastre is at the core of any LAS.

The spatial data infrastructure provides access to and

interoperability of the cadastral information and other land

information.

The cadastre provides the spatial integrity and unique

identification of every land parcel usually through a cadastral map

updated by cadastral surveys. The parcel identification provides the

link for securing rights in land, controlling the use of land and

connecting the ways people use their land with their understanding of

land.

The land parcel is the foundation of the hierarchy because it

reflects the way people use land in their daily lives. It is the key

object for identification of land rights and administration of

restrictions and responsibilities in the use of land. The land parcel

links the system with the people.

The hierarchy illustrates the complexity of organizing policies,

institutions, processes, and information for dealing with land in

society. But it also illustrates an orderly approach represented by the

six levels. This conceptual understanding provides the overall guidance

for building LAS in any society, no matter the level of development. The

hierarchy also provides guidance for adjustment or reengineering of

existing LAS. This process of adjustment should be based on constant

monitoring of the results of the land administration and land management

activities. The land policies may then be revised and adapted to meet

the changing needs in society. The change of land policies will require

adjustment of the LAS processes and practices that, in turn, will affect

the way land parcels are held, assessed, used, or developed.

5. SPATIALLY ENABLED GOVERNMENT

Place matters! Everything happens somewhere. If we can understand

more about the nature of “place” where things happen, and the impact on

the people and assets on that location, we can plan better, manage risk

better, and use our resources better (Communities and Local Government,

2008). Spatially enabled government is achieved when governments use

place as the key means of organising their activities in addition to

information, and when location and spatial information are available to

citizens and businesses to encourage creativity.

New distribution concepts such as Google Earth provide user friendly

information in a very accessible way. We should consider the option

where spatial data from such concepts are merged with built and natural

environment data. This unleashes the power of both technologies in

relation to emergency response, taxation assessment, environmental

monitoring and conservation, economic planning and assessment, social

services planning, infrastructure planning, etc. This also include

designing and implementing a suitable service oriented IT-architecture

for organising spatial information that can improve the communication

between administrative systems and also establish more reliable data

based on the use of the original data instead of copies.

Spatial enablement offers opportunities for visualisation,

scalability, and user functionalities. This is related to institutional

challenges with a range of stakeholder interests. This includes

Ministries/Departments such as: Justice; Taxation; Planning;

Environment; Transport; Agriculture; Housing; Regional and Local

Authorities; Utilities; and civil society interests such as businesses

and citizens. Creating awareness of the benefits of developing a shared

platform for Integrated Land Information Management takes time. The

Mapping/Cadastral Agencies have a key role to play in this regard. The

technical core of Spatially Enabling Government is the spatially enabled

cadastre.

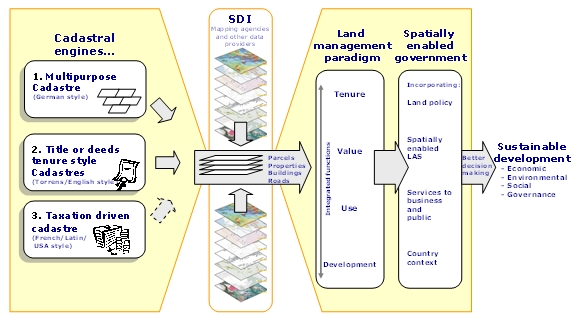

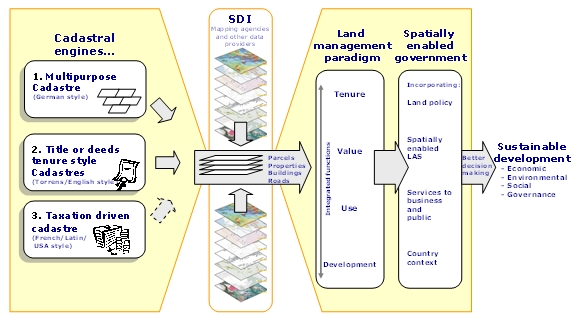

5.1 Significance of the Cadastre

The land management paradigm makes a national cadastre the engine of

the entire LAS, underpinning the country’s capacity to deliver

sustainable development. The role of the cadastre as the engine of LAS

is neutral in terms of the historical development of any national

system, though systems based on the German and Torrens approaches, are

much more easily focused on land management than systems based on the

French/Latin approach. The cadastre as an engine of LAS is shown

diagrammatically in figure 5.

Figure 5. Significance of the Cadastre (Williamson, Enemark,

Wallace, Rajabifard, 2009)

The diagram highlights the usefulness of the large scale cadastral

map as a tool by exposing its power as the representation of the human

scale of land use and how people are connected to their land. The

digital cadastral representation of the human scale of the built

environment, and the cognitive understanding of land use patterns in

peoples’ farms, businesses, homes, and other developments, then form the

core information sets that enable a country to build an overall

administrative framework to deliver sustainable development.

The diagram demonstrates that the cadastral information layer cannot

be replaced by a different spatial information layer derived from

geographic information systems (GIS). The unique cadastral capacity is

to identify a parcel of land both on the ground and in the system in

terms that all stakeholders can relate to, typically an address plus a

systematically generated identifier (given addresses are often

duplicated or are otherwise imprecise). The core cadastral information

of parcels, properties and buildings, and in many cases legal roads,

thus becomes the core of SDI information, feeding into utility

infrastructure, hydrological, vegetation, topographical, images, and

dozens of other datasets.

5.2 Good governance

Governance refers to the manner in which power is exercised by

governments in managing a country’s social, economic, and spatial

recourses. It simply means: the process of decision-making and the

process by which decisions are implemented. This indicates that

government is just one of the actors in governance. The concept of

governance includes formal as well as informal actors involved in

decision-making and implementation of decisions made, and the formal and

informal structures that have been set in place to arrive at and

implement the decision. Good governance is a qualitative term or an

ideal which may be difficult to achieve. The term includes a number of

characteristics: (adapted from FAO, 2007):

- Sustainable and locally responsive: It balances the

economic, social, and environmental needs of present and future

generations, and locates its service provision at the closest level

to citizens.

- Legitimate and equitable: It has been endorsed by society

through democratic processes and deals fairly and impartially with

individuals and groups providing non-discriminatory access to

services.

- Efficient, effective and competent: It formulates policy

and implements it efficiently by delivering services of high quality

- Transparent, accountable and predictable: It is open and

demonstrates stewardship by responding to questioning and providing

decisions in accordance with rules and regulations.

- Participatory and providing security and stability: It

enables citizens to participate in government and provides security

of livelihoods, freedom from crime and intolerance.

- Dedicated to integrity: Officials perform their duties

without bribe and give independent advice and judgements, and

respects confidentiality. There is a clear separation between

private interests of officials and politicians and the affairs of

government.

Once the adjective “good” is added, a normative debate begins. In

short: sustainable development is not attainable without sound land

administration or, more broadly, sound land management.

6. FACING THE NEW CHALLENGES

The key challenges of the new millennium are clearly listed already.

They relate to climate change; food shortage; energy scarcity; urban

growth; environmental degradation; and natural disasters. These issues

all relate to governance and management of land. Land governance is a

cross cutting activity that will confront all traditional

“silo-organised” land administration systems.

Land governance and management is going to be a core area for the

surveyors – the land professionals. This area requires high level

geodesy to create the models that can predict future changes; modern

surveying and mapping tools that can control implementation of new

physical infrastructure and also provide the basis for the building of

National spatial data infrastructures; and finally sustainable land

administration systems that can manage the core functions of land

tenure, land value, land use, and land development.

FIG (the International Federation of Surveyors) intend to play a

strong role in building the capacity to design, build and manage

national surveying and land administration systems that facilitates

sustainable Land Governance in support of the MDGs. In short, FIG is

aiming at “Building the capacity for taking the land policy agenda

forward”.

7. FINAL REMARKS

The MDGs represent a wider concept or a vision for the future, where

the contribution of the land professionals is central and vital. FIG,

being a global NGO representing the surveying community/land

professionals in more than 100 countries throughout the world, is

strongly committed to the global agenda as presented in the MDGs.

The surveyors – nationally and globally – will have a key role as

providers of the relevant spatial information and also as builders of

efficient land tenure systems and effective measures for urban and rural

land use management. The role of FIG is about “Building the Capacity” in

this area.

Issues such as tenure security, pro-poor land management, and good

governance in land administration are all key issues to be advocated in

the process of contributing to the global agenda. Measures such as

capacity assessment, institutional development and human resource

development are all key tools in this regard. More generally, the work

of the land professionals within land management forms a kind of

“backbone” in society that supports social justice, economic growth, and

environmental sustainability. These aspects are all key components in

facing the global agenda.

REFERENCES

- Augustinus, C., Lemmen, C.H.J. and van Oosterom, P.J.M. (2006)

Social tenure domain model requirements from the perspective of pro

- poor land management. Proceeding of the 5th FIG regional

conference, 8-11 March 2006, Accra, Ghana.

http://www.fig.net/pub/accra/papers/ps03/ps03_01_augustinus.pdf

- Communities and Local Government (2008): Place matters: the

Location Strategy for the United Kingdom.

http://www.communities.gov.uk/publications/communities/locationstrategy

- Enemark, S. (2004): Building Land Information Policies.

Proceedings of Special Forum on Building Land Information Policies

in the Americas. Aguascalientes, Mexico, 26-27 October 2004.

http://www.fig.net/pub/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf

- Enemark, S. and McLaren, R. (2008): Preventing Informal

Development – through Means of Sustainable Land Use Control.

Proceedings of FIG Working Week, Stockholm, 14-19 June 2008.

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig2008/papers/ts08a/ts08a_01_enemark_mclaren_2734.pdf

- Higgins, M. (2009): Positioning Infrastructures for sustainable

Land Governance. Proceedings of FIG/WB Conference on Land Governance

in Support of the MDGs, Washington, 9-10 March 2009.

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig_wb_2009/papers/sys/sys_1_higgins.pdf

- UN-Habitat (2008): Secure Land Rights for all. UN Habitat,

Global Land Tools Network.

http://www.gltn.net/en/e-library/land-rights-and-records/secure-land-rights-for-all/details.html

- Williamson, Enemark, Wallace, Rajabifard (2009): Land

Administration Systems for Sustainable Development. ESRI Press. In

press.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Stig Enemark is President of the International Federation of

Surveyors, FIG 2007-2010. He is Professor in Land Management and Problem

Based Learning at Aalborg University, Denmark, where he was Head of

School of Surveying and Planning 1991-2005. He was President of the

Danish Association of Chartered Surveyors (DdL) 2002- 2006 and he is an

Honorary Member of DdL. He is a well known international expert in the

areas of land administration systems, land management and spatial

planning, and related educational and capacity building issues. He has

published widely in these areas and undertaken consultancies for the

World Bank and the European Union especially in Eastern Europe, Sub

Saharan Africa.

CONTACTS

Prof. Stig Enemark

FIG President

Department of Development and Planning,

Aalborg University, 11 Fibigerstrede

9220 Aalborg, DENMARK

Email: [email protected]

Website:

www.land.aau.dk/~enemark

|