Key words: Cadastre, Standards, 3D, 3D Cadastre,

Inventory

SUMMARY

In this paper, the background, set-up, and a preliminary

analysis of the survey conducted by the FIG joint commission 3 and 7

working group on 3D-Cadastre, 2010-2014 is presented. The purpose of the

survey is to make a world-wide inventory of the status of 3D-Cadastres

at this moment (November 2010) and the plans/expectations for the near

future (2014). Sharing this information improves cooperation and

exchange of experiences and supports future developments in different

countries and cadastral jurisdictions. The FIG working group will repeat

the survey in four years time to evaluate the actual progress. In the

questionnaire the concept of 3D-Cadastres with 3D parcels is intended in

the broadest possible sense. At the moment of writing, 36 completed

questionnaires have been received. Another detailed questionnaire survey

is being conducted among the eight cadastral jurisdictions of Australia,

and the results from these are also presented and compared to the

international situation. At the moment of writing, all completed

Australian questionnaires have been received.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the past decade various activities have been

conducted related to 3D-Cadastres. The start of the international

awareness of this topic was marked by the workshop on 3D-Cadastres

(sponsored by FIG commissions 3 and 7), organized by Delft University of

Technology in November 2001. This was followed by virtually a session at

every FIG working week and congress afterwards (stimulated by the

2002-2006 FIG working group on 3D-Cadastres). Within cadastral

organizations this was paralleled by on-going developments at Cadastral

organizations in many countries to provide better 3D-support. The

increasing complexity of infrastructures and densely built-up areas

requires a proper registration of the legal status (private and public),

which only can be provided to a limited extent by the existing 2D

cadastral registrations. Despite all research and progress in practice,

no country in the world has a true 3D-Cadastre, the functionality is

always limited in some manner; e.g. only registering of volumetric

parcels in the public registers, but not included in a 3D cadastral map,

or limited to a specific type of object with ad hoc semi-3D solutions;

e.g. for buildings or infrastructure.

At the FIG Congress in April 2010 in Sydney it was

decided to form again a working group on 3D-Cadastres in order to make

further progress with the subject; see Section 2 for more details of

this working group. The registration of the legal status in complex 3D

situations will be investigated under the header of 3D-Cadastres.

Starting point of the working group is the observation that increasingly

information is required on rights, use and value in complex spatial

and/or legal situations.

There are several 3D-Cadastre scoping options, which

need to be investigated in more detail by the working group, and the

result will define the scope of the future 3D-Cadastre in a specific

country:

-

What are the types of 3D cadastral objects that need

to be registered? Are these always related to (future) constructions

(buildings, pipelines, tunnels, etc.) as in Norway and Sweden or

could it be any part of the 3D space, both airspace or in the

subsurface as in Queensland, Australia?

-

In case of (subsurface) infrastructure objects, such

as long tunnels (for roads, metro, train), pipelines, cables: should

these be divided based on the surface parcels (as in Queensland,

Australia) or treated as one cadastral object (as in Sweden). In

case of subdivision, note that to all parts rights (and parties)

should be associated.

-

For the representation (and initial registration) of

a 3D cadastral object, is the legal space specified by its own

coordinates in a shared reference system (as is the practice for 2D

in most countries) or is it specified by referencing existing

topographic objects/boundaries (as in the 'British' style of a

cadastre).

Note that there can be a difference between the 3D

ownership space and the 3D restriction space; e.g. one can be owner up

to ±100 m around the earth surface, but only allowed to build from -10

to +40 m. Both result in 3D parcels, that is, 3D spatial units with RRRs

attached. The ownership spaces (parcels) should not overlap other

ownership parcels, but they are allowed to overlap other space; e.g.

restriction parcels.

Part of the activities of the working group is to make a

world-wide inventory of the status of 3D-Cadastres at this moment

(November 2010) and the plans/expectations for the near future (2014);

see Section 3. This will be done via a repeated questionnaire: one in

2010 (status 2010 and plans 2014) and one in 2014 (status 2014 and plans

2018). The repeated survey in four years time will be helpful to

evaluate the actual progress. Sharing this information improves

cooperation and exchange of experiences and supports future developments

in different countries and cadastral jurisdictions. A related survey has

been conducted among the eight cadastral jurisdictions of Australia (see

Section 4). The results and preliminary analysis of the international

FIG 3D-cadastres survey is presented in Section 5. Finally, Section 6

contains the conclusions and description of future work in the area of

3D-Cadastres.

2. FIG WORKING GROUP ON 3D-CADASTES

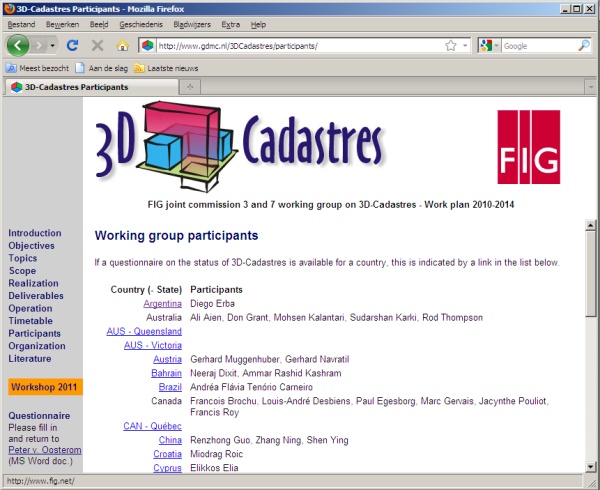

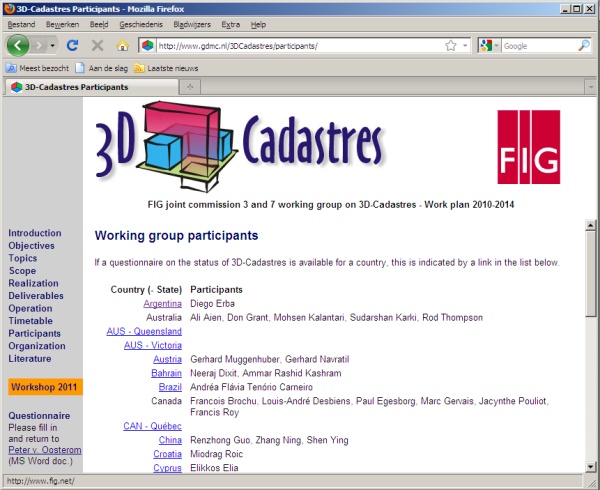

This section presents the FIG joint commission 3 and 7

working group on 3D-Cadastres (2010-2014). In subsection 2.1 the

objectives of the working group are formulated. The main research topics

of the working group are presented in subsection 2.2, while deliverables

and mode of operation are introduced in subsection 2.3. For more

information on the FIG working group on 3D-Cadastres, including the

overview of relevant 3D cadastre literature and the 35 completed

questionnaires, see the website of this working group

www.gdmc.nl/3DCadastres.

2.1 Objectives

The main objective of the working group is to establish

an operational framework for 3D-Cadastres. The operational aspect

addresses the following issues:

-

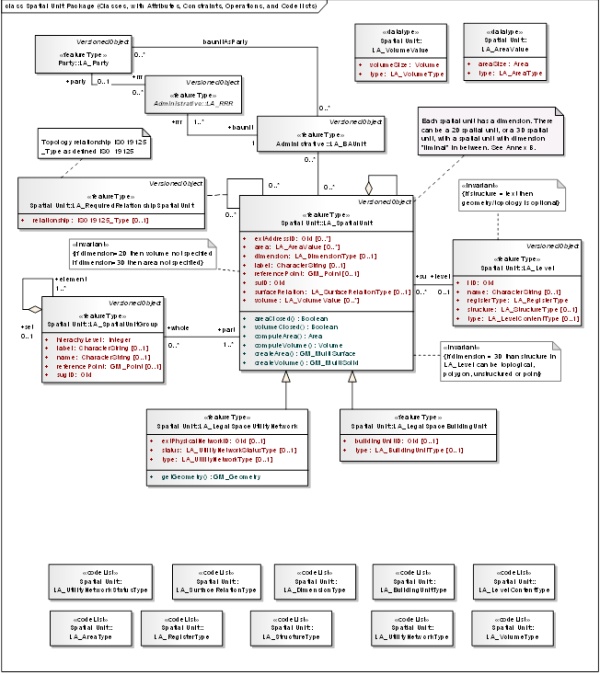

A common understanding of the terms and issues

involved. After the initial misunderstandings (due to lacking shared

concepts and terminology) in the early days, the concepts should now

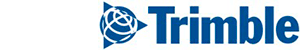

be further refined and agreed on, based on the ISO 19152 Land

Administration Domain Model (LADM, which provides support for 3D

representations); see Figure 1.

-

A description of issues that have to be considered

(and to what level) before whatever form of 3D-Cadastres can be

implemented. One could think of a checklist for the implementation

of 3D-Cadastres. These will provide 'best practices' for the legal,

institutional and technical aspects. These findings will be

translated in basic guidelines for the implementation of

3D-Cadastres.

Figure 1. ISO 19152 with 3D spatial units and specializations

such as LA_LegalSpaceUtilityNetwork and LA_LegalSpaceBuildingUnit

By means of pursuing these issues we hope to have a

fruitful exchange of ideas. There exists not a unique 3D-Cadastre. In

all cases for the establishment of such a cadastre legal, institutional

and technical issues have to be addressed. The level of sophistication

of each 3D-Cadastre will in the end be based on the user needs, land

market requirements, legal framework, and technical possibilities.

Therefore, in line with ISO's LADM it is our objective to explore the

optimal trade-offs between 2D and 3D cadastral solutions (the full

replacement of a 2D-Cadastre by a 3D-Cadastre is not an issue, but we

need to address the issues that arise in the transition zones).

The working group will focus primarily on professionals

involved in geo-information and cadastral issues in 3D. This community

will also provide the contributors to the working group. Access to this

interest group is open to all. Once the results become more tangible the

FIG-community at large will be our public.

Within the working group the concept of 3D-Cadastres

with 3D parcels is intended in the broadest possible sense. 3D parcels

include land and water spaces, both above and below surface. However,

what exactly is (or could be) a 3D parcel is dependent on the legal and

organizational context in the specific country (state, province). For

example, in one country a 3D parcel related to an apartment unit is

associated with an ownership right, while in another country the

government may be owner of the whole apartment complex and the same

apartment unit is related to a use right. In both cases there are

explicit 3D parcels, but with different rights attached. A third country

may decide not to represent the apartment units with explicit 3D

geometries at all (and the 3D aspect is then 'just' conceptual). A more

formal definition: A 3D parcel is defined as the spatial unit against

which (one or more) unique and homogeneous rights (e.g. ownership right

or land use right), responsibilities or restrictions (RRRs) are

associated to the whole entity, as included in a Land Administration

system. Homogeneous means that the same combination of rights equally

apply within the whole 3D spatial unit. Unique means that this is the

largest spatial unit for which this is true. Making the unit any larger

would result in the combination of rights not being homogenous. Making

the unit smaller would result in at least 2 neighbour 3D parcels with

the same combinations of rights.

2.2 Research topics

The working group identified four main research topics:

models, Spatial Information Infrastructure (SII, sometimes also called

SDI), temporal aspects and usability. These four topics are elaborated

on below:

-

3D-Cadastres and models: It is important to realize

that for registration, for storage/validation and for dissemination

different models (all based on the shared ISO LADM semantics) may be

needed and different types of users are involved. The modelling

aspect includes the question of which spatial (esp. height) and

temporal information should be used and how different types of users

may interact (i.e. produce, archive, edit, analyze, and visualize,

edit) with 3D-Cadastre? The 'users' belong to various categories;

they range from professionals (which can be further subdivided in

notary, real estate brokers, banks, water boards, utility companies,

municipalities, cadastral employees, surveyors, etc.) to citizens

(with various capabilities of owners/users: from computer

illiterates to experienced web surfers/gamers).

-

3D-Cadastres and SII: The registration of legal

objects (cadastral parcels and associated rights) and their physical

counterparts (e.g. buildings or tunnels) result into two different,

but related data sets, which can be very well accessed together via

the Spatial Information Infrastructure (SII, sometimes also called

SDI). This is already true in 2D, but even more so in 3D. By also

showing some physical objects for reference purpose, the location

and size of the legal objects will be clearer.

-

3D-Cadastres and time: A 4D parcel is defined as the

spatio-temporal unit against which (one or more) unique and

homogeneous rights (e.g. ownership right or land use right),

responsibilities or restrictions are associated to the whole entity,

as included in a Land Administration system. Homogenous means that

the same combination of rights equally apply within the whole 4D

spatial temporal unit. Unique means that this is the largest

spatio-temporal unit for which this is true. Making the unit any

larger (in 3D space or time) would result in the combination of

rights not being homogenous. Making the unit smaller (in 3D space or

time) would result in at least 2 neighbour 4D parcels with the same

combinations of rights.

-

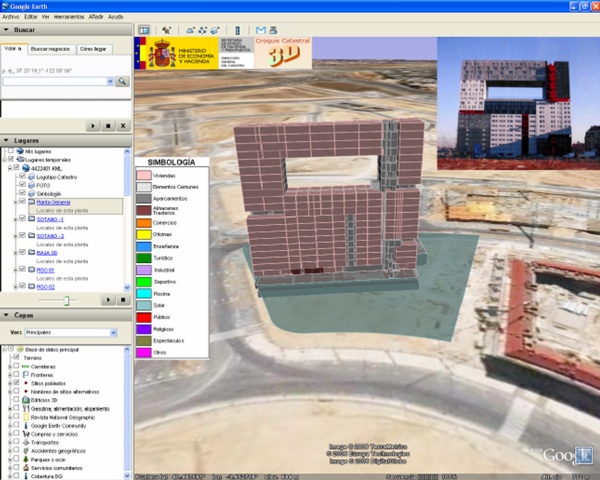

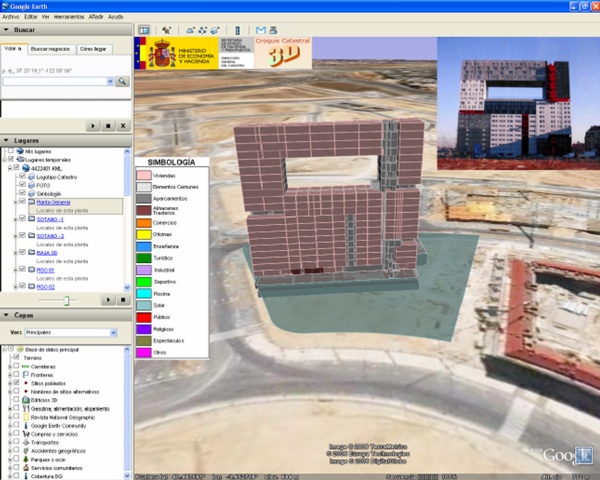

3D-Cadastres and usability: The graphic user

interface (GUI) is an essential aspect when realizing 3D-Cadastres

in practice. This includes investigation of interacting with true 3D

cadastral data (specific user interfaces: 3D spatial and perhaps

temporal aspects via animations or snapshot sliders). The existing

quality of successful and popular user interfaces (such as Google

Earth; see Figure 2) will be the starting point with specific

attention for working with the main 3D legal object types (related

to underground infrastructure and building/apartment complexes). A

true 3D cadastral system with functions should be implemented and

applied to demonstrate the possibilities in practice based on 3D

visualization. How to distribute the 3D cadastral information (3D

parcels and associated rights) to the citizens? How to represent and

demonstrate the 3D geographic aspect, on paper (with different

viewpoints) or on electronic media (interactive tools based on Adobe

Flex or Flash)?

Figure 2. 3D visualisation in

Google Earth (example Spanish cadastre)

2.3 Deliverables and operation

The working group strives to obtain tangible results

that have relevance to the cadastral practice. At the next FIG congress

(2014) we want to publish a FIG publication on guidelines to establish

3D-Cadastres (a 'Primer on 3D-Cadastres'), addressing legal,

institutional and technical issues. In 2011 a second workshop on

3D-Cadastres is planned (again in Delft, 10 years after the first

workshop). In addition, at the FIG working weeks joint commission 3 and

7 sessions on 3D-Cadastes will be organized. Depending on the need and

results, additionally a third workshop on 3D-Cadastres could be

organized in 2013 or 2014 preferably in conjunction with another FIG

meeting (working week, or commission 3/7 annual or congress). Each

workshop will be accompanied by a brief progress report. The exchange of

ideas and discussions will be facilitated by means of a website on

3D-Cadastres. Depending on the issues encountered in our first or second

year of operation a survey of user needs (e.g. by means of a

questionnaire) might be useful.

At the FIG events in the past decade many people have

expressed their interested in 3D-Cadastres. In order to push ahead it

seems best if the specific themes of 3D-Cadastres (legal, institutional

and technical) are lead by a limited number of experts (2-4) who

elaborate on their subject. People can then join these groups for

discussion and preferably contributions. Task of the chair is to start

and encourage these theme-groups, lead the overall issues of working

group, and trigger the necessary events. It seems wise to evaluate this

way of working after one year. Communication during the projects will be

done as much as possible by e-mail and via our dedicated website:

www.gdmc.nl/3DCadastres;

see Figure 3. At the end of each year a progress report will be

available to all members of the interest group and our sponsors in

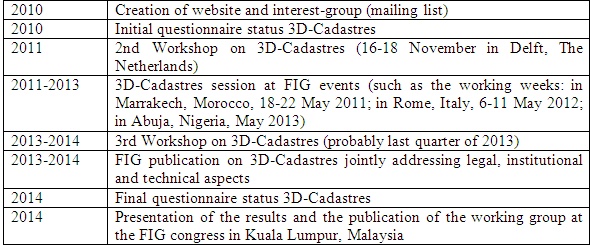

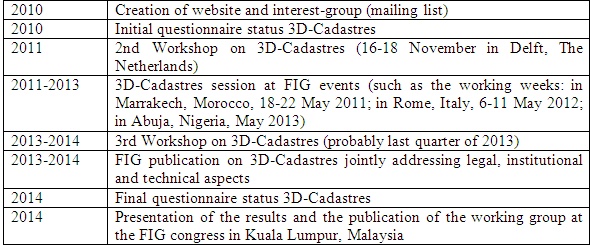

commissions 3 and 7. The Table 1 shows the main events of the working

group in time.

Figure 3. Website FIG 3D Cadastres (with participants and their

completed questionnaires)

Table 1. Timetable with events of

the FIG working group on 3D-Cadastres

3. DESIGN OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE

In this section the design (set-up) of the questionnaire

is presented. No matter how much effort one puts in setting-up a

questionnaire, the experience shows that the questions are always less

clear to the persons/organizations that have to fill in the

questionnaires compared to how clear the questions are to the persons

that created the questions (even if this was a larger team of persons as

in case of the 3D-Cadastres questionnaire). This is caused by the fact

that different terms may have slightly different meaning to persons in

different countries in the world. This is especially true for more

abstract concepts such as 3D Cadastre and 3D parcel. Therefore the first

page of the questionnaire contained a few notes (including an informal

and a formal definition of a 3D parcel) and suggestions, which should be

helpful during the completing the questionnaire. To lower the threshold

to complete (and return) the questionnaire it was also explicitly

expressed that ‘If a certain question is not relevant or if you have no

clue what to respond, do not spend any time on this (and leave the field

blank).’

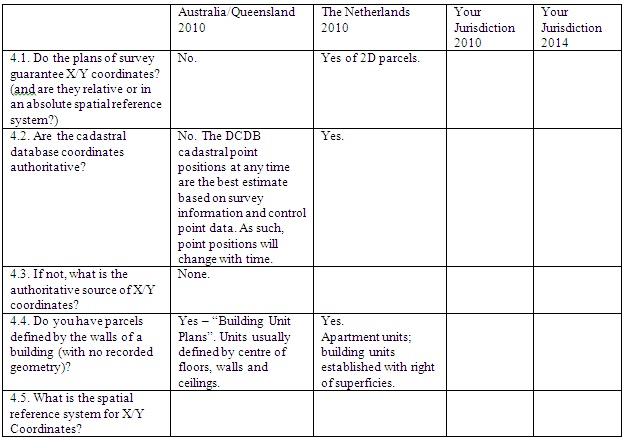

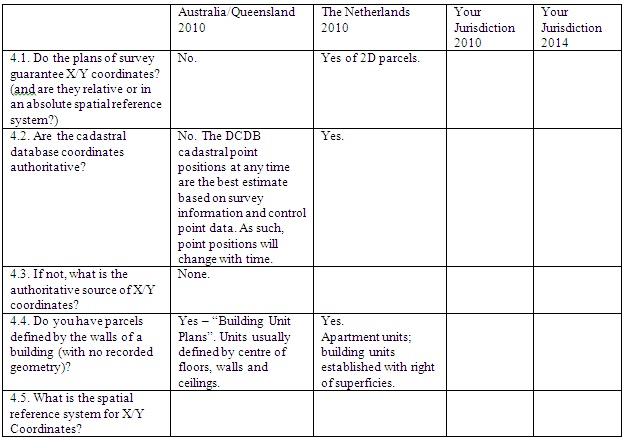

The formal definition a 3D parcel is defined as the

spatial unit against which (one or more) unique and homogeneous rights

(e.g. ownership right or land use right), responsibilities or

restrictions are associated, as included in a Land Administration

system. As this definition is quite abstract, the questions were phrased

with more descriptive and real world situations included to explain

further. Also two example sets of partial/preliminary answers were

included from Queensland, Australia and The Netherlands, to support the

questions and to be of help when formulating the answers for other

jurisdictions (see Table 2). Despite or due to these preparations during

the period of completing of the questionnaire the organizers received

two requests for clarification.

The questionnaire specifically aims at clarifying the

difference between 3D legal space (referred to as 3D parcel) and 3D

physical objects. A 3D parcel is a ‘legal object’ describing a part of

the space. Often there is a relationship with a real world/physical

object, which can also be described in 3D, but this is not invariably

the case. The questionnaire was framed to recognise the difference

between these two types of objects and that the focus in the context of

3D-Cadastres is on 3D parcels (spaces of legal objects). The

questionnaire has been prepared by the authors of this paper. The

questionnaire was grouped in different thematic blocks. This had no

meaning in the sense of priority and it was often possible that a

question could belong to multiple blocks. The following nine groups of

questions were indentified:

-

General/applicable 3D real-world situations

-

Infrastructure/utility networks

-

Construction/building units

-

X/Y Coordinates

-

Z Coordinates/height representation

-

Temporal Issues

-

Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities

-

DCDB (The Cadastral Database)

-

Plans of Survey (including field sketches)

The first group of questions refers to the applicable 3D

real-world situations to be registered by 3D parcels. It also addressed

the types of 3D geometries, which are considered to be valid 3D

representations for these parcels. The second group of questions refers

to the situation where an infrastructure network is considered to be

defined within the cadastre. For example in some jurisdictions, an

underground network might be privately constructed for the purpose of

leasing space in it for other organisations to run cabling. In this

case, a network, or part of that network may be considered to be a real

estate object. The third group of questions refers to 3D properties that

are related to constructions and apartment (condominium) buildings. The

individual units are often defined by the actual walls and structure of

a building, rather than by metes and bounds. E.g. “unit 5 on level 6 of

… building”. The other 6 groups of questions are more or less

self-evident. Finally, group 10 the contact details could be provided

together with any other issue that was relevant, but not yet addressed

by one of the earlier questions.

Table 2. Sample form the

3D-Cadastres questionnaire (section 4. X/Y Coordinates) with example

answer from Australia/Queensland and The Netherlands (for the 2010).

The questionnaire was distributed among the member of

FIG 3D-Cadastres WG and the members of FIG joint commission 3 and 7. The

respondents were asked to complete the two empty columns for their

jurisdiction: 2010 (the current status) and 2014 (expectations in 4

years time).

4. AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE

The idea for a 3D-Cadastres questionnaire was first

‘born’ in Australia. Therefore we start by presenting these results.

This questionnaire has been conducted among the eight cadastral

jurisdictions of Australia: Queensland, Australian Capital Territory,

New South Wales, Northern Territory, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria

and Western Australia (Karki, Thompson, McDougall 2011).. The results

from these are summarised and compared to the international situation.

Generally speaking, the states of Australia have

different procedures, but attempt to have consistent regulations as far

as the public is concerned. This is to ensure that “loop-holes” are not

generated by state differences. Differences, when they occur, tend to be

in the situations that have come into existence more recently. Thus the

first question “Are all 3D parcels constrained to be within one surface

(2D) parcel?” has elicited quite different responses, probably because

situations such as the subdivision of a surface parcel which has a 3D

parcel below it is still a rare occurrence.

4.1 Results of the Australian questionnaire

The range of responses to the Australian questionnaire

was well within the international results (see below), but in summary:

-

All jurisdictions allow 3D parcels to be defined by

metes and bounds (without reference to a physical structure),

-

Alternately all allow parcels to be defined by a

physical structure.

-

All allow a wide range of parcel definitions

(possibly including curved surfaces) providing a precise definition

is made.

-

Dealings involving 3D parcels are effectively the

same as for 2D, but there are some additional restrictions on rights

to units in strata.

-

Moving parcels and temporal boundaries are not

implemented (although there was confusion in some of the replies)

4.2 Differences Between Australian and FIG Responses

In the Australian context, all states support a “heaven

to centre of earth” approach for rights on most parcels. There are

parcels with restricted rights in the form of ownership rights or

encumbrance in the strata. Sometimes even the rights or encumbrances in

strata are sub-divided, amalgamated or nullified. However, distinction

is made between a 2D parcel plan and 3D plan (Volumetric or Building

Format). For a Building Format plan which is used to represent strata,

the database records a 2D surface parcel outline and the various level

details as attributes. For a Volumetric Parcel, easements or leases can

be created for the whole parcel or part of the parcel above or below the

ground.

Below are some of the differences between the Australian

and the International context:

-

Constraints to be within the surface 2D parcel:

In Australia, 2D parcels are subdivided to reflect 3D ownership,

however if the 2D parcels are subsequently subdivided or amalgamated

it does not affect the status of the 3D parcel with then may span

several 2D parcels. 3D easements or leases may exist on part or the

whole of a 2D parcel, may extend to other parcels, may be

subdivided, amalgamated or wholly or partly extinguished and may

have full or partial overlap with another interest.

-

Empty Spaces or Existing Constructions: 3D

rights are permitted as in the case of 3D easements, limited height

parcels or Building Format parcels. For example, an apartment block

which is demolished with the owners rights being reserved for a

replacement on the same level and aspect but not the exact airspace

as before. By contrast a parcel (e.g. a marina parcel) may be

defined by its location in space without reference to any

construction.

-

Boundaries of the 3D parcel: The cadastral

survey requirement is quite explicit in that the 3D parcel

boundaries to be formed must be measurable or definable

mathematically. Volumetric plans and Building format plans deal with

strata quite differently. A Volumetric plan uses an absolute height

(Reduced Level based on the Australian Height Datum) on the surface

while using bearing and distance for the edges, with an isometric

drawing provided. A Building Format plan provides an outline of the

surface parcel, the building footprint and details of each level

while distinguishing between common property and areas of each items

such as the main building, patio, balcony, private yards etc.

-

Registration of 3D parcels in the cadastral

database: 3D registration is supported by the titling system and

3D parcels are registered as either a Volumetric parcel or as a

Building Format parcel. In the digital cadastral database, the

strata are shown as an attribute and all 3D related information

exists in the plan. Building Format plans are not created for every

house, but only those requiring strata title. The title database is

held separately to the cadastral database and updates are part of a

sequential workflow. 3D data is not represented in the viewing tools

of the database.

-

Registration of cable and pipeline networks:

There seems to be quite a number of ways network parcels are

registered in Australia. While some create 3D easements, others

subdivide the surface parcels and some do not capture them on plans.

2D parcels generally have a minimum size restriction determined by

zoning rules but there is no such restriction on the minimum

cross-section size of a 3D parcel.

5. PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF THE RESPONSES

In this section, the preliminary analysis of the survey

conducted by the FIG joint commission 3 and 7 working group on

3D-Cadastre, 2010-2014 is presented. In total 36 completed

questionnaires have been received and they are all available at the

working group website (http://www.gdmc.nl/3DCadastres/participants/).

All members of the working group responded with exception of the USA

(until) today: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Brazil, Canada,

China, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece,

Hungary, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Macedonia,

Malaysia, The Netherlands, Nepal, Nigeria, Norway, Poland, Russia, South

Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, and

United Kingdom. Despite all the efforts to make the concepts used in the

questionnaire and the questions asked as clear as possible, we received

a few requests for clarification by the respondents. This shows the

difficulty (and also the importance) to formulate a clear, standardized

definition for 3D cadastre and 3D parcels that will fit all

jurisdictions.

From the completed questionnaires we received, a number

of conclusions can be made. The first is that despite all the research

in the past year the concepts "3D cadastre” and “3D parcels" are still

ambiguous. The completed questionnaires offer therefore in the first

place an overview of the very different ways in which systems of land

administration deal with the third dimension of rights (or

restrictions). Worldwide there are major differences in those systems,

mostly the result of cultural and historical differences in background,

and these differences influence the organizational, technical and legal

aspects of land registration. Because of these differences, a comparison

of the responses is not always easy.

A general conclusion is that in all jurisdictions, with

the exception of Poland and Nepal, 3D parcels can be registered. But in

most cases these 3D parcels are (or even limited to) apartment units.

That it is not possible to register 3D parcels other than apartment

units in a specific land administration does not mean automatically that

it is not possible to create rights that are limited in the third

dimension. E.g. in the case of South Korea the respondent explicitly

indicated that 3D boundaries of rights are possible by civil law, while

cadastral regulation does not touch this subject. In the following

paragraphs we give an overview of the preliminary analysis of survey

results for several aspects.

5.1 Are all 3D parcels constrained to be within one

surface (2D) parcel?

Most respondents replied on question 1.1 of the

questionnaire that a 3D parcel must be located within the boundaries of

a (2D) parcel. This does not exclude that the building to which the

right refers may be situated on several land parcels. Possibly - as in

the case of the Netherlands - a legal 3D description of right refers to

various 2D land parcels. The responses are not always clear on the

question what will happen if the land parcel is subdivided later. In

Queensland it is the starting point that the 3D parcel must be within

the boundaries of a 2D parcel, but this does not exclude that the 2D

parcel may be subdivided later on. After subdivision the original 3D

parcel continues to exist and therefore stretches out over two or more

land parcels. In Norway and Sweden, 3D properties may be created that

extend over or under different 2D parcels. In Finland this possibility

is foreseen for the future.

5.2 Empty spaces or existing constructions?

An interesting question is whether registration of

rights to empty spaces - such as air spaces or subsurface volumes - is

allowed (e.g. to protect an existing panorama) or that the registered

right compulsory refers to an existing or future construction. This

topic had been addressed by question 1.3. The responses shows that in

most countries explicit rules for this do not exist, but also indicated

that in general the rights will refer to a construction. Explicitly the

possibility of registration of rights for empty spaces are mentioned in

Australia and Canada (Quebec), In Finland this is limited to subsurface

volumes. By contrast, Norway and Sweden the law expressly exclude this

possibility. In these countries there must be a construction, or a

building permit issued for future constructions before a 3D property can

be registered. In Norway 3D parcels can be nullified in the case

construction has not started building the construction that is going to

be the 3D property three years after the building permit has been

issued.

5.3 Boundaries of the 3D parcel

Generally the boundaries of 3D parcels refer to walls,

ceilings and floors. The respondent for France expressly states that -

in the absence of guidelines in this area - virtual boundaries would be

possible. With respect to the z-axis (height) it appears that in the

vast majority of systems directives on this issue does not exist or the

height is not registered. Among the countries that do register the

height (in survey plans or in a legal deed) it may be observed that

Australia and France make use of an absolute level while in Canada

(Quebec) and Sweden reference is made to a height relative to ground

level.

5.4 Registration of 3D parcels in the cadastral

database

3D parcels as such do not exist in any cadastral

registration. The description of the 3D space will be found in the

survey plans or in the legal documents. The standard seems to be that

"floorplans" that the boundaries per floor are listed in the title deed

or the appropriate public records (Land Book, Land Registry, public

records) or survey plans but not in the cadastral database (map). It may

be possibly a make a reference to the 3D parcel in the cadastral map in

the form of a 2D polygon in a single layer as in the case of Australia,

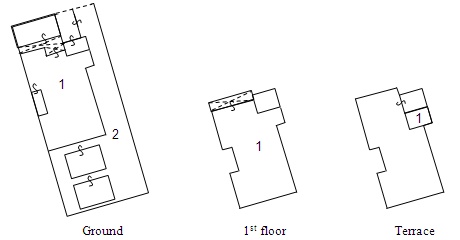

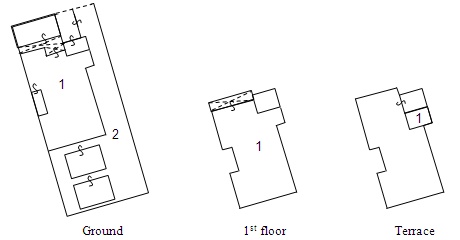

Cyprus (see Figure 4), Croatia (where is spoken of a “2.5D

representation”) , Norway and Sweden.

Figure 4. Example from Cyprus:

floor plan with 2 cadastral objects at ground, 1st, and 2nd floor

(terrace)

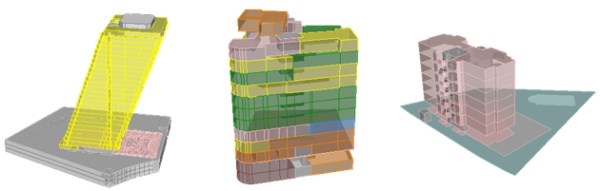

In Italy 3D Cadastre in Italy is represented by the

Cadastre of Buildings, that exists next to the “Land Cadastre”. This

holds an inventory of every building. A very interesting system of 3D

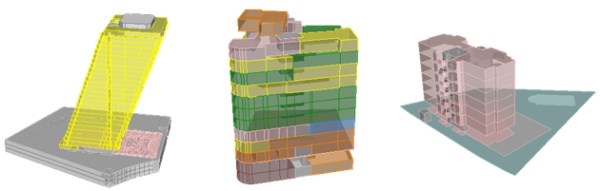

registration exists in Spain. Here on the cadastral map a 3D model of

the buildings can be shown, including the boundaries of rights inside

the buildings. But this is not a 3D representation of the actual height

of the units. In fact the representation is based on a standard height

of 3 meters from floor-to-floor. Although this is a limitation, this

solution does offer a more or less a realistic view of the buildings and

property rights within buildings in urban areas, see Figure 5.

Figure 5. 3D visualisation of

buildings in the Spanish cadastre (based on a standard floor-to-floor

height of 3 meter.

5.5 Registration of cable and pipeline networks

Cable and pipeline networks occupy a special place

within the registered 3D objects and rights. These networks often extend

over several land parcels and thus have - apart from the height or depth

of the structure - a 3D character of their own. In recent years the

Netherlands introduced the possibility to register rights to all types

of cable and pipeline networks. The networks have a cadastral number of

their own. In Switzerland, especially in Geneva networks are included in

the cadastral database in a similar way. In the Russian Federation, a

network can be registered by the Land Registry, but in practice this is

not done. In Kazakhstan, all networks are registered "as legal objects".

However the respondent also mentions that underground networks are not

registered but only shown on maps. Furthermore, in Canada (Quebec) cable

and pipeline networks, rail networks are recorded in public registers

(Register or real right of State resource development). It can be

requested by the owner that the network is displayed on the cadastral

plan, but this rarely happens. The network as such can not be found in

the cadastral database, but indirectly through the land parcels in which

the network is constructed.

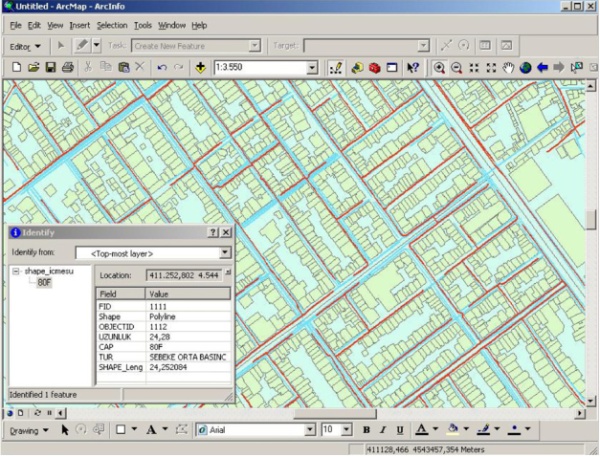

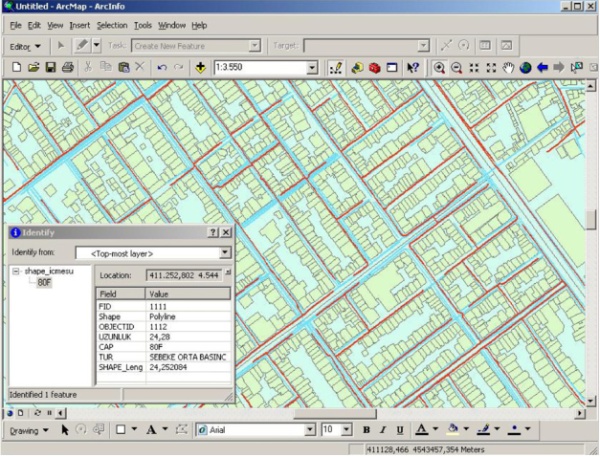

Figure 6. Turkish example ‘3D utility network’: gas (red) and

water (blue) map fragment Istanbul reregistered utility data in

combination with cadastral map; translation: ‘uzunluk’ = ‘length’, ‘cap’

= ‘diameter’,‘tur’ = ‘pressure’; source (Döner e.a. 2010).

In other countries registration of networks does not

happen, or is just possible in limited cases, as in Turkey where only

high voltage power lines are registered in the cadastral database.

Registration of other networks find place at municipal level, and

combined with cadastral data, see Figure 6 example from Istanbul,

Turkey. A general registration of (underground) networks does not exist

in Norway, where telecommunications, water and electricity networks are

not registered, but roads and railways are. Some jurisdictions have

"utility maps” (Australia, Victoria) or a" utility register " as

Croatia. In the latter country is expected that this register will be

integrated in the cadastral database in 2014. Also in other countries we

see developments towards the cadastral registration of networks,

especially in Denmark, Hungary, Israel and Italy. In the latter country

this would take place in the context of pilots projects leading to the

development of a subsurface cadastre.

5.6 Developments in the short term

The purpose of the survey by the FIG Working group was

not only to make a world-wide inventory of the status of 3D-Cadastres at

this moment (2010/2011), but also to get an insight in the expectations

for the near future (2014). However, the planned developments in the

field of 3D cadastre for 2014 seem to be very limited. Whether this

means that one is satisfied with the existing system of 2D registration,

like the respondent for England and Wales expressly stated, remains

unclear. The vast majority of respondents did not answer the questions

one the expected situation for 2014. The most concrete developments

seems to happen in Switzerland, where in 2014 the concept of 3D plots

might be introduced, and Denmark, where the respondent mentions an

ongoing discussion of 3D parcels should be recorded in the cadastre and

a footprint on the cadastral map. Bahrain mentions the future

representation of the apartments in the cadastral database. In recent

years in Israel there has been much research into the development of a

3D cadastre and preparations aimed at legislation and it is hoped that

this will result in practical changes.

6. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

As indicated, the solutions for registration of rights

with 3D characteristics are very different. Broadly, one can observe

that apartments are registered with drawings in the deed registration.

But a true 3D registration in the cadastre does not exist anywhere. Most

often it was approached by Spain, although the representation uses a

standard height per floor layer.

Techniques for 3D data acquisition, management and

distribution will be within reach. The next step is to optimally exploit

this in order to meet the growing information needs in 3D cadastres,

matching specific organizational and legal contexts. The international

approach of the FIG working group hopes to make an important

contribution to reach this, by the publication of “Primer on

3D-Cadastres” providing guidelines for specific contexts and

implementations, addressing legal, institutional and technical issues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors of this paper would like to express their

sincere gratitude to the members of the FIG joint commission 3 and 7

working group on 3D-Cadastres for their joint efforts to complete the

questionnaires: Diego Erba, Ali Aien, Don Grant, Mohsen Kalantari,

Gerhard Muggenhuber, Gerhard Navratil, Neeraj Dixit, Ammar Rashid

Kashram, Andréa Flávia Tenório Carneiro, Francois Brochu, Louis-André

Desbiens, Paul Egesborg, Marc Gervais, Jacynthe Pouliot, Francis Roy,

Renzhong Guo, Zhang Ning, Shen Ying, Miodrag Roic, Elikkos Elia, Lars

Bodum, Esben Munk Sørensen, Christian Thellufsen, Jani Hokkanen, Arvo

Kokkonen, Tarja Myllymäki, Claire Galpin, Hervé Halbout, Markus Seifert,

Efi Dimopoulou, Gyula Iván, Andras Osskó, Trias Aditya, S. Subaryono,

Yerach Doytsher, Joseph Forrai, Gili Kirschner, Yoav Tal, Bruno Razza,

Enrico Rispoli, Fausto Savoldi, Natalya Khairudinova, David Siriba,

Gjorgji Gjorgjiev, Vanco Gjorgjiev, Alias Abdul Rahman, Babu Ram

Acharya, Benedict van Dam, Chrit Lemmen, Thomas Dabiri, Lars Elsrud,

Olav Jenssen, Lars Lobben, Tor Valstad, Jaroslaw Bydlosz, Vladimir

Tikhonov, Natalia Vandysheva, Youngho Lee, Amalia Velasco, Jesper

Paasch, Jenny Paulsson, Helena Aström Boss, Robert Balanche, Laurent

Niggeler, Charisse Griffith-Charles, Cemal Biyik, Osman Demir, Fatih

Döner, Gareth Robson, and Carsten Roensdorf. Of course, the authors

remain responsible for the correct interpretation and the resulting

article.

REFERENCES

-

Fatih Döner, Rod Thompson, Jantien Stoter,

Christiaan Lemmen, Hendrik Ploeger, Peter van Oosterom and Sisi

Zlatanova (2010). 4D cadastres: First analysis of Legal,

organizational, and technical impact - With a case study on utility

networks. In: Land Use Policy, Volume 27, pp. 1068-1081, 2010.

-

ISO (2011), ISO 19152. Draft International Standard

(DIS), Geographic information — Land administration domain model

(LADM), Geneva, Switzerland, 20 January 2011.

-

P.J.M. van Oosterom, J.E. Stoter, E.M. Fendel (Eds.)

(2001); Proceedings International Workshop on 3D Cadastres,

Registration of properties in strata, Delft, November 2001,

published by FIG (online www.gdmc.nl/3DCadastres/literature)

-

S. Karki, R.J. Thompson, K McDougall (2011):

Analysis of 3D Cadastral situation in Australia, Unpublished Paper,

2011

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Peter van Oosterom obtained an MSc in Technical

Computer Science in 1985 from Delft University of Technology, The

Netherlands. In 1990 he received a PhD from Leiden University for this

thesis ‘Reactive Data Structures for GIS’. From 1985 until 1995 he

worked at the TNO-FEL laboratory in The Hague, The Netherlands as a

computer scientist. From 1995 until 2000 he was senior information

manager at the Dutch Cadastre, were he was involved in the renewal of

the Cadastral (Geographic) database. Since 2000, he is professor at the

Delft University of Technology (OTB institute) and head of the section

‘GIS Technology’. He is the current chair of the FIG joint commission 3

and 7 working group on ‘3D-Cadastres’ (2010-2014).

Jantien Stoter defended her PhD thesis on 3D

Cadastre in 2004, for which she received the prof. J.M. Tienstra

research-award. From 2004 till 2009 she worked at the International

Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, ITC,

Enschede, the Netherlands (www.itc.nl). As associate professor at ITC

she led the research group in the field of automatic generalization. She

was project leader of an EuroSDR project on generalisation from 2005

till 2009. Since October 2009, she fulfils a dual position: one as

Associate Professor at Section GIS technology at OTB and one as

Consultant Product and Process Innovation at the Kadaster. From both

employers she is posted to Geonovum. The topics that she works on are

3D, information modelling and multi-scale data integration. Since

January 2010 she leads the 3D pilot that aims at establishing a 3D

reference model in The Netherlands in a collaboration of 55 partners. In

November 2010 she received a VIDI grant, which is a prestigious award

given by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) for

excellent senior researchers

Hendrik Ploeger studied law at Leiden University

and the Free University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. In 1997 he

finished his PhD-thesis on the subject of the right of superficies and

the horizontal division of property rights in land. He is associate

professor at Delft University of Technology (OTB Research Institute) and

holds the endowed chair in land law and land registration at VU

University of Amsterdam. His research expertise focuses on land law and

land registration, especially from a comparative legal perspective.

Rod Thompson has been working in the spatial

information field since 1985. He designed and led the implementation of

the Queensland Digital Cadastral Data Base, and is now principal advisor

in spatial databases. He obtained a PhD at the Delft University of

Technology in December 2007.

Sudarshan Karki is senior Spatial Information

Officer, Cadastral & Geodetic Data (Survey Information Processing Unit),

in the Data Management & Acquisition, Spatial Information Group of

Department of Environment and Resource Management, Queensland

Government, Australia. He completed his professional Masters Degree in

Geo-informatics from ITC, The Netherlands in 2003 and is currently doing

Master of Spatial Science by Research at the University of Southern

Queensland.

CONTACTS

Peter van Oosterom

Delft University of Technology

OTB, Section GIS-technology

P.O. Box 5030

2600 GA Delft

THE NETHERLANDS

Tel. +31 15 2786950

Fax +31 15 2784422

E-mail:

[email protected]

website http://www.gdmc.nl

Jantien Stoter

Delft University of Technology + Kadaster

OTB, Section GIS-technology

P.O. Box 5030

2600 GA Delft

THE NETHERLANDS

Tel. +31 15 2781664

Fax +31 15 2784422

E-mail: [email protected]

website http://www.gdmc.nl

Hendrik Ploeger

VU University Amsterdam, Faculty of Law &

Delft University of Technology

OTB, Section Geo-Information and Land management

P.O. Box 5030

2600 GA Delft

THE NETHERLANDS

Tel.: + 31 15 2782557

Fax: + 31 15 2782745

Email:

[email protected]

Website: www.juritecture.net

Rod Thompson

Queensland Government, Department of Environment and Resource Management

Landcentre,

Main and Vulture Streets,

Woolloongabba

Queensland 4102

AUSTRALIA

Tel. +61 7 38963286

E-mail: [email protected]

Web site:

http://www.derm.qld.gov.au/

Sudarshan Karki

Queensland Government, Department of Environment and Resource Management

Landcentre,

Cnr Main and Vulture Streets,

Woolloongabba

Queensland 4102

AUSTRALIA

Tel.: +61 7 389 63190

Fax: +61 7 389 15168

E-mail:

[email protected]

Web site:

http://www.derm.qld.gov.au/