Article of the Month -

July 2012

|

3D Cadastre in the Federal Countries of Latin America

Diego Alfonso ERBA and Mario Andrés PIUMETTO, Argentina

1) This paper was presented

at the FIG Working Week 2012 in Rome Italy, and the main question asked

is: Is it realistic to develop spatial concepts for parcels and legal

land objects and to propose a 3D cadastral model in the federal

countries of Latin America at this time? The conclusion indicates that

this is the right time to start thinking about it, compiling the

legislation and systematizing the 2D definitions as a first step. Latin

America occupies approximately 15% of the Earth's land surface and

therefore a focus on this continent is appropriate. The next FIG

Regional Conference will therefore take place in Uruguay, 26-29 November

2012, with emphasis on the challenges of the region.

Key words: 3D Cadastre, Federal Countries Cadastre, Latin

America

SUMMARY

Latin America is a vast region of the world, occupying approximately

15% of the Earth's land surface. The 20 countries that compose it have

around 400 regional governments (states or provinces) and 16,000 local

governments. The region is characterized by a variety of races,

landscapes, languages and dialects, climates, history and political

systems, in which only 4 countries are governed under federalist

regimes. In this system the power is divided among the national,

regional and/or local governments, with Constitutions that define each

level´s attributions. Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Venezuela, together,

have 65% of the region’s population and a similar percentage of surface

area of Latin America.

The concepts of parcels, their identification and description, the

extension of the properties, the restrictions of property rights, and

many other aspects related to the cadastre are different. This paper

compares the cadastral structure and the registration of land right in

the federal countries of Latin America, describes the main existing

legal land objects in the legislation, and provides a perspective for

implementation of a 3D Cadastral system for each of them, under the

legal vision.

1. INTRODUCTION

In most Latin American countries, the cadastral systems were created

under the orthodox physical-economic-legal models imported from Spain

and Portugal. In recent years, the multipurpose cadastral model has been

gaining acceptance in the region as a new alternative, better suited to

the needs of administrators and the public. The spread and gradual

implementation of Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDI) in the region is a

sign of the willingness to share data and investments among different

institutions.

The question that inspired this paper was: Is it realistic to develop

spatial concepts for parcels and legal land objects and to propose a 3D

cadastral model in the federal countries of Latin America at this time?

The conclusion indicates that this is the right time to start thinking

about it, compiling the legislation and systematizing the 2D definitions

as a first step.

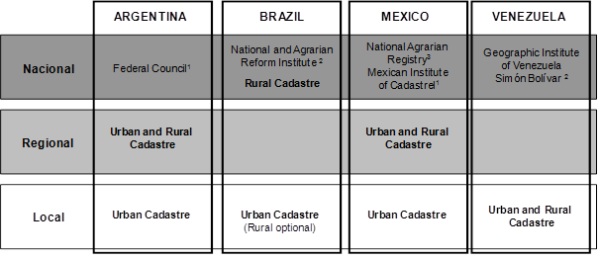

2. CADASTRAL ORGANIZATION IN THE LATIN AMERICAN FEDERAL COUNTRIES

In

Argentina there is no single system, as the provinces never

delegated the cadastral function to the federal government. In fact, one

interesting feature of the Argentine system is that, although the

country has a National Cadastral Law and a Federal Cadastral Council

that establishes general guidelines, each federative body has its own

provincial cadastral law and specific regime. Therefore, the provinces

organize their territorial cadastres to identify the physical, economic

and legal aspects of the parcels, and use that data to define their land

tax policies. In parallel, some municipalities organize their urban

cadastres with the main goal of enforcing planning standards, mainly as

it pertains to the subdivision of land, and use that data to define the

service fees collection policies. The connection between the municipal

and provincial cadastres is made at different levels around the country.

In

Brazil, federalism has a particular connotation when it comes to

managing territorial information. While the rural cadastre is organized

by the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform, which is

part of the central government, and is therefore centralized (although

distributed around the country), local governments organize their

municipal cadastres with ample authority and independence, focusing

mainly on the cities. Given the enormous diversity of criteria, and as

an alternative for the municipalities that lack the needed human,

technical and financial resources, the Ministry of Cities has published

National Guidelines for the Creation of a Multipurpose Cadastre which –

although lacking the force of law – guide technical and administrative

personnel through cadastral restructuring.

In

Mexico, public information on real estate is obtained from

cadastres and registries. As there were inconsistencies in many cases,

some states decided to place both institutions under the same roof (in

some cases only “legally”, in others “physically”). Neither the Federal

Constitution nor any statute mandates a cadastral function. The

attributions given to municipalities by Art. 115 of the Carta Magna,

induced some local governments to set up cadastres, and so did at least

half the states in the country. Therefore, we can identify 3 basic

systems: The cadastres that are completely centralized at the state

level; the state cadastres that have been decentralized to the

municipalities; and the state cadastres that work in parallel with the

municipal cadastres. The social property created by the Mexican

revolution is managed by the National Agrarian Registry, which can be

considered a form of rural cadastral registry. The recent creation of

the Mexican Cadastral Institute (Instituto Mexicano de Catastro) and the

Mexican Society of Assessors and Cadastral Management Specialists

(Sociedad Mexicana de Especialistas en Valuación y Gestión Catastral)

opens up the possibility of establishing clear criteria and goals,

matched to the facts on the ground.

In

Venezuela, the Geography, Cartography and National Cadastral Law

establishes guidelines to restructure the country’s cadastres. According

to this law, Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar Geographic Institute directs,

coordinates and executes policies and plans for the creation and

maintenance of cadastres throughout the country, and Municipal Cadastral

Offices are obligated to organize their cadastre following these

national directives. Many times, the various limitations of local

governments to create and maintain a cadastre make this task impossible,

so the Institute provides support, mainly by developing joint projects

and collaborating to obtain resources from the pertinent public

agencies, without precluding the participation of the private sector.

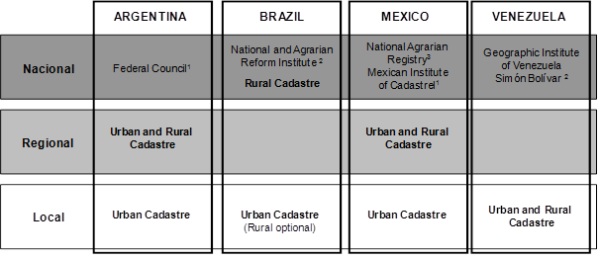

Figure 1 shows a

comparison of the cadastral organization of the four federal countries.

Figure 1

1consulting institutions, 2institutions with cadastral

functions 3 for social land property

3. PERSPECTIVES OF A 3D CADASTRE IN LATIN AMERICA

The conceptualization of a 3D cadastral model requires a clear

understanding of the physical occupancy of the territory and the current

legal framework. Regarding the urban aspect, the virtualization of the

different existing cities in the region is essential because it allows

us to analyze how 3D parcels can be defined, represented and described;

and how the 3D legal land objects restrict them.

This understanding is crucial to the development of a 3D structure for

the cadastres of the Latin American federal countries, and their

relationships with 3D land registries as well as the 3D land use

restrictions laws.

3.1 Virtual 3D Cities in Latin America

Among the different realities and technological levels of Latin American

countries, there are interesting experiences indicating that development

of 3D urban cadastral models in the region is possible in the median

term.

Entering the 3D world could start with the creation of different virtual

3D cities. In the context of this paper, a “virtual 3D” city is the real

(built) city which, represented geometrically, is useful in several

types of analyses, such as vehicular traffic studies, tracking of cell

phone waves, or any type of infrastructure network analysis. For other

kinds of analysis the virtual 3D city it is not sufficient, as when a

lawyer may need to visualize the legal 3D city as defined by urban and

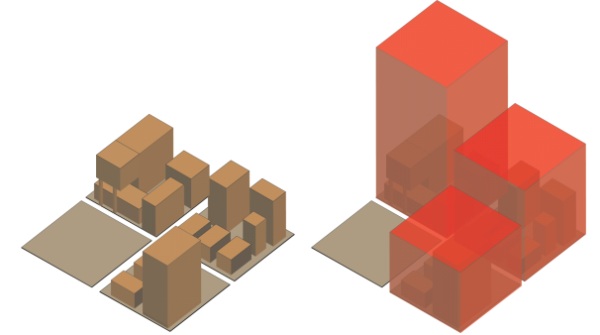

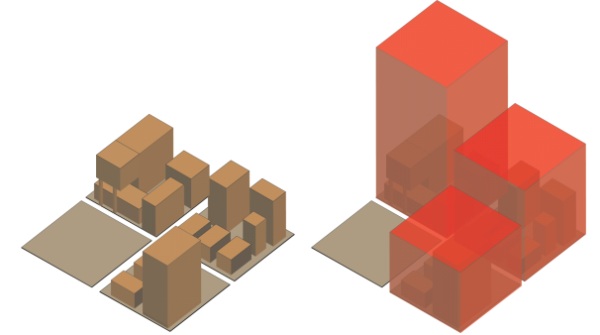

environmental regulations. Figure 2 shows two virtual 3D cities, one

representing existing formal buildings and the other indicating the

legal city according to its development potential based on the

applicable urban regulations.

Figure 2 – Representations of the Virtual 3D

formal city and the Virtual 3d legal city

Note: The existing buildings on the left are incorporated into an

expanded legal city on the right. Source: prepared by Diego Erba and

Anamaria Gliesch-Leebmann.

In

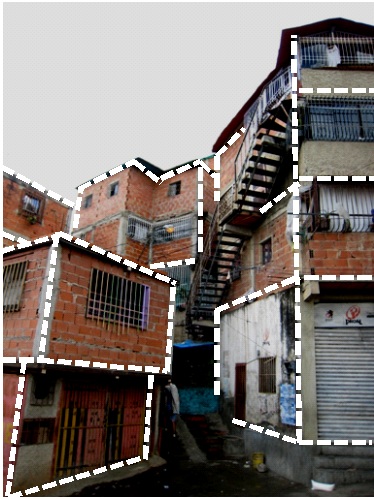

Latin America, where the incidence of urban informality is practically a

constant in the urban landscape, it is important to visualize and define

the informal as well as the legal 3D virtual city. Every “occupied

space” is a part of the city and should be considered in the urban data

bases of the cadastre.

Informal settlements develop when people are unable to save money or

obtain access to credit to purchase a home or are ineligible to receive

government assistance through housing programs. They must find a place

to settle, which is often on hazardous or protected land that is

inappropriate for housing, or on vacant public or private land. The

magnitude of the need for housing often surpasses the amount of land

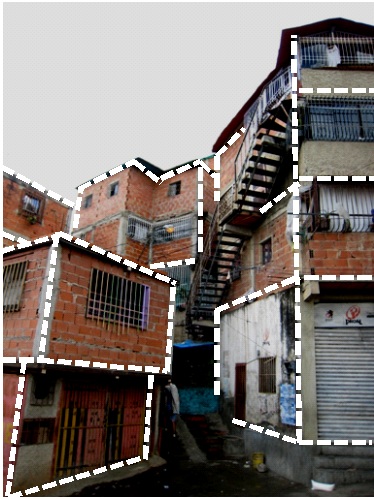

available, thus pushing informal settlers to build taller structures at

higher densities that in many ways are similar to those in the formal

housing market (figure 3).

Figure 3 -

Improvised housing units in an informal settlement in Caracas, Venezuela

Source: © Martim Smolka; rendering by Diego Erba.

Urban properties and their surroundings are conditioned by different

kinds of restrictions described by legal land objects.

3.2 Legal Land Objects in the federal countries of

Latin America

The

concept of a land object arose with the “cadastre 2014” model as a piece

of land in which homogeneous conditions (normally defined by law) exist

within its boundaries. The definition affirms that if a law defines

phenomena, rights, or restrictions related to a fixed area or point of

the surface of the Earth, it defines a land object - LO.

Incorporating legal aspects, the concept was extended, to affirm that a

piece of land could be called a legal land object - LLO, when either a

private or a public law imposes identical juridical parameters. The laws

define the limits of a right or a restriction. The LLO normally is

defined by boundaries which demarcate where a right or a restriction

ends and where the next begins, and everything that right encompasses.

The

definitions are clear only for a 2D dimension connotation. Some examples

of the LLO mentioned in the document confirm this vision: private

property parcels; areas where traditional rights exist; administrative

units such as countries, states, districts, and municipalities; zones

for the protection of water and nature and for protection against

noise and pollution; land use zones; areas where the exploitation

of natural resources is allowed, etc.

The

construction of the 3D LLO concept can be based on the 2D definition,

and that is the reason why this study started identifying the legal

framework which describes the LLO in the federal countries.

It

is not common to find the terms LO or LLO in Latin American legislation.

In Argentina, the National Cadastral Law No. 26.209 defines “legal

object” as any portion of the territory that by nature and means of

access is finite and homogeneous. A “legal land object” (objeto

territorial legal) is one that is generated by a legal cause. This legal

cause may be a property title (as is the case in real estate

transactions), an ordinance or law (as is the case in ownership

restrictions, the creation of reservation areas, or the demarcation of

an urban area), or even an international treaty (such as those that

establish borders between countries). The law stipulates that all LLOs,

and their public records, must be managed by the provincial cadastres.

In

the rest of the Latin American countries, the definition of LLOs is not

as explicit as in Argentina, but proof of their existence can be seen in

substantive and ancillary legislation.

We

describe below 5 subject areas that meet the LLO definition in 4 Latin

American countries.

3.2.1

Environmental spaces and surroundings

In

Argentina, the National Law No. 25.509/2001 established a real

estate right to a forested area. It is conveyed separately from land

ownership, and allows somebody to plant in another parcel, but keep

ownership of what was planted. In addition, it allows for the purchase

of existing plantations in parcels that belong to others. This is a

temporary right, with a maximum duration of 50 years, and can be

canceled if it is not used for 3 or more years. This right is granted by

contract and must be recorded in the Registry of Deeds.

Argentina is the only country where glaciers can be found. The National

Law No. 26.639 of 2008 places restrictions for the conservation of

glaciers and the peri-glacial environment. Art. 3 creates a National

Glacier Inventory, with useful information to protect, control and

monitor glaciers. Art. 4 stipulates that the National Glacier Inventory

shall contain information about each glacier and its peri-glacial

environment classified by hydrologic watershed, location, area and

morphology. The inventory must be updated at least every 5 years, and

capture the changes in the glacier surface and its peri-glacial

environment. This last article stipulates, among others, the obligation

to measure the surface of the glacier and monitor it periodically to

determine any changes in its size. This law does not make any volumetric

references, even though it would be particularly interesting to study

changes in glaciers over time.

In

Brazil, the environmental legislation has a large scope. Two

areas are highlighted within the context of this work, which are still

defined under the 2D vision: legal reserve, and permanent protection

areas.

According to the Forestry Code (Act No. 4771/1965), a legal reserve is

an area located within a rural property or land, except for a permanent

protection area, which is necessary for the sustainable use of natural

resources, the conservation and restoration of ecological processes, the

conservation of biodiversity, and the preservation and protection of

native fauna and flora (section 1, §2º, III). Therefore, a legal reserve

is a portion of a rural property whose owner or possessor commits

him/herself to preserve the native vegetation. The vegetation of a legal

reserve cannot be eliminated, although the owner may use it under the

sustainable forestry management regime, as per the applicable legal

principles and technical-scientific criteria (section 16, §2º).

Permanent protection areas are protected by the Forestry Code. They may

or may not be covered by native vegetation, and have the environmental

function of preserving water resources, landscapes, geological

stability, biodiversity, and fauna and flora gene flows, as well as

protecting the soil, and securing the well-being of human populations

(section 1, §2º, II). These areas are characterized as such

regardless of their location, the use of the property or their

ownership, since they can be public or private properties. Some examples

of permanent protection areas are: the margins of any water courses (a

land portion varying from 30 meters to 500 meters); natural springs

(within a 50-meter radius); the top of hills, mountains and ranges; and

hillsides with over 45% slope.

In

Mexico, protection of environmental areas is governed by the laws

of “Environmental Equilibrium and Environmental Protection” and

“Sustainable Forest Development”. In both cases, the legislation imposes

no restrictions on property, nor does it establish special regimes for

forests or open spaces that limit property rights and are subject to

real registration. Nonetheless, both laws establish a broad set of

regulations and mechanisms related to zoning that contribute to regulate

use of these resources. For correct administration of this information,

it must be included in a spatial database as well as in the country’s

cadastral databases. An exception to this rule in the Federal District

(Mexico City) is the District Environmental Law, which establishes that

such restrictions must be registered in the Public Property Registry

(art. 98).

In

Venezuela, the Forest and Forestry Management Law (Decree

6070/2008) restricts the use of properties that have certain native

forests or are registered for forest use by the applicable authorities.

In no case are these considered unused or unproductive land, so no

compensation can be claimed, and they can only be expropriated in

exceptional cases. In addition, the law establishes “ecological

easements” in perpetuity over the parcels located in “protection zones”

and “forestry reserve areas,” as defined by the applicable authorities,

and the landowners are responsible for identifying these easements on

their land and recording them in their property titles. A special case

of ecological easement is the “protection zones of mountain and mesa

ranges”, which are strips of at least 300 meters on each side of

mountain ranges and inclined mesa slopes. (ref. art. 21, 22, 32, 33, 35,

39 a 42)

3.2.2 Water resources and

their surroundings

In

Argentina the restriction to private ownership around rivers is

established in Article 2639 of the Civil Code. This towpath is defined

as a 35 meter strip measured from the shore of navigable waterways

toward the interior of adjoining properties. No compensation can be

claimed for this area, and it implies a hands-off or non-interference

obligation.

In

Brazil, there are differences in the restrictions related to the

sea and the navigable lakes and rivers. The “terrenos de marinha” (Union

sea-land properties) are those areas which, washed by sea or navigable

river waters, reach up to 33 meters into the land, counted as from the

mean high water point. This point refers to the condition of the place

at the time of execution of section 51, §14 of the Act enacted on

11/15/1831 (section 13 of the Water Code, Executive Order No.

24.643/1934). These are public properties, i.e., such land portion is

not part of the private property. The “terrenos reservados” (reserved

lands) are those which possess navigable currents out of the reach of

tides, which reach a 15-meter distance, measured horizontally towards

the land from the median line of ordinary floods (section 14 of the

Water Code). Generally, the reserved lands on the shores of lakes and

navigable rivers belong to the states (Water Code – Executive Order

24,643/34, section 31), except when the river is owned by the Federal

Government, in which case the reserved land's title is owned by the

Union (section 31 of the Water Code, together with section 20, clause

III of the Federal Constitution). As in the case of Union sea-land

properties, reserved lands are not part of private properties.

In

Mexico, the “National Law on Water” complements Article 27 of the

Mexican Constitution on matters related to superficial or subsoil

national waters. The law foresees a towpath specifically called “Federal

Bank or Zone”, which must be 10 meters wide contiguous to the waterway,

measured horizontally from the maximum regular level of water. The

length of the federal bank or zone must be five meters in the river bed,

with a width no greater than five meters.

In

Venezuela, the Waterways Law, in its Article 6, stipulates that

all waterways, inland, marine or insular, superficial or underground,

are in the country’s public domain. Strips of land 80 meters on each

side of non-navigable or intermittent rivers, and 100 meters on each

side of navigable rivers, are also in the public domain.

The

same law stipulates that, because these waterways are in the public

domain, they cannot be part of the private domain of any physical or

legal person. Underground waters are in adjacent domains: the state owns

the resources, while a private party may own the land, its airspace and

subsoil, except for situations that can only be managed in 3D space.

Article 54 of this law attempts to protect the sensitive areas on which

the water, plants and wildlife depend for their existence and quality,

by declaring certain lands part of “protected zones of water bodies.”

These zones restrict the domain - with no right to compensation – in: a)

a surface defined by a circumference with a 300 m radius projected

horizontally and centered in the source of any waterway; and b) a 300 m

strip on either side of rivers, measured from the edge of the high water

mark; and from the borders of lakes and natural lagoons.

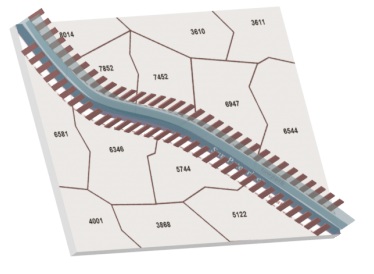

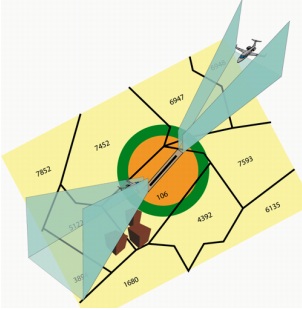

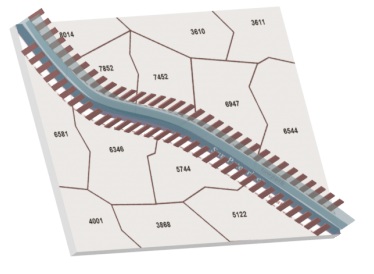

Figure 4 - Towpath

3.2.3 Underground spaces and concessions

In Argentina the

Mining Code was established by Decree No. 456 of 1997. It regulates the

property of mines, and the rights of exploration and operation. In Art.

7, it stipulates that the mines are private assets of the Federal

Government or the Provinces, depending on their location. Art. 10 of the

Mining Code stipulates that “independently of the original ownership by

the State… the private property of the mines can be established by legal

grant”. This granting of mining rights can be interpreted as a mining

easement to the mining company. On the other hand, Art. 12 defines the

mines as real estate properties. Art. 20 establishes a mining

cadastre to describe the physical, legal, and other useful information

about mining rights. Those rights are identified with points that

represent the vertices of the “area” defined in the requests for

exploration permits, discovery manifests, etc. However, the Mining Code

does not mandate in any of its articles the volumetric representation of

the mineral to be explored.

In

Brazil, according to the Federal Constitution, Article 176,

mining reserves, whether active or not, and other mineral resources and

the potential for hydroelectric power, are a type of property that is

different from the property of soil, for the purposes of exploitation or

use, and as such they belong to Brazil. However, the grantee has a right

to own the product that is mined from such area. Similar to the

Argentine Code, the Brazilian legislation does not provide any

information regarding volume.

In

Peru, mineral rights are established by Supreme Decree #014-92-EM

(Unified Text of the General Mining Act) and regulated by Supreme Decree

#03-94-EM. Section II of the Preliminary Title of this legislation

establishes that all mineral resources belong to the State, and that

this ownership is inviolable and inalienable. Act #26615 creates the

Mining Cadastre, whose unit of measure is the mineral right, a property

unlike land or the right of property under or over land, and therefore

is not the same as a parcel, as established in paragraphs 1 and 8 of

Article 885 of the Civil Code. The General Mining Act expressly states

in Article 9: “The concession of mining rights is a real estate property

distinct and separate from the parcel where said rights are located."

In

Mexico, Article 12 of the Mining Law refers to the “mining lot”

and describes is using elements that reveal it as more of a “mining

space”. According to the law, it is a solid body of undefined depth,

delimited by vertical planes and whose upper limit is the surface of the

Earth, based on which the corresponding perimeter is determined. The

sides that make up the perimeter of the lot must be oriented

astronomically both North-South and East-West, and the longitude of each

side must be in multiples of one hundred meters, except when these

conditions cannot be met because the lot meets other mining lots. The

location of the mining lot is determined based on a fixed point in the

lot, called the starting point and connected with the perimeter of or

located on the lot. The description affirms that the link of the

starting point will preferably be perpendicular to any of the sides

(North-South or East-West) of the lot’s perimeter. Despite the fact that

their descriptions are not georeferenced, mining spaces clearly have a

vertical development.

In

Venezuela, the Mining Law (Decree 295/1999) stipulates in Article

2 that mineral deposits of any kind belong to the country’s public

domain, and must be recorded in the Public Registry. The law describes

in detail how to distinguish the land from the subsoil where the mineral

deposits are stored; in its Article 10, it states: “for the purpose of

this Law, the earth’s crust is divided into two parts: the land, which

is the surface layer and the area below it affected by the work of the

landowner in activities other than mining; and the subsoil, which

extends indefinitely in depth from the point the land ends. The mining

activities in the subsoil do not generate compensation for the

landowner, except if they affect the land or other assets.” Article 26

defines an area of mining rights as “a pyramidal volume, whose base is a

rectangular horizontal plane measured in hectares, and whose vertices

and sides are oriented pursuant to a projection system adopted by a

competent authority”, and in Article 28: “the horizontal extension of

the mining rights shall be a rectangle defined by fixed points and

straight lines over the earth’s surface, whose surface unit is the

hectare (Ha.) Its vertical extension shall be defined by the projection

of this horizontal extension to the center of the Earth, with no depth

limit.

The right to explore and exploit mineral substances within the space

volume assigned constitutes a real estate right (Article 29) and must be

recorded in the Public Registry (Article 45).

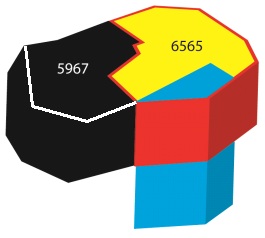

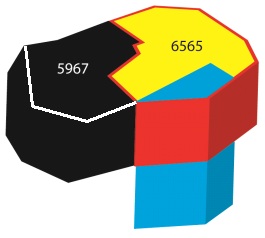

Figure 5 - Underground spaces

3.2.4

Aerial space and use restrictions

In

Argentina the Aeronautic Code was established by National Law No.

17.285 of 1967, and it describes the limitations to ownership of

property located close to airports. This Code defines the limits to

obstacles in the airspace in airports and their surrounding environment,

to ensure the secure landing and takeoff of aircraft. Although these

obstacles are by nature volumetric bodies, they are represented by their

surface projections on land. However, cross-sections are also enclosed

to describe the height over land over which the restriction extends.

In

Brazil the Law 7,565 of 1986 regulates the Air Code. The

restrictions to which neighboring properties of airports are

subject have to do with the use of such properties and the buildings,

premises, types of crops that can be farmed, and anything that may

hinder the operation of airplanes or cause interference to the radio

signals used to assist air traffic or block the visibility of visual

signs.

In

Mexico, the Civil Aviation Law, in Chapter 1 – General

Provisions, Article 1 – defines the use or exploitation of the airspace

over the national territory for the purpose of providing and developing

civil and government air transportation. The law states that the

airspace over the national territory is a general communication pathway

subject to the domain of the Federal Government. The Civil Aviation Law

regulations define the events that may occur in the airspace,

emphasizing the importance of a 3D definition.

In

Venezuela, the Civil Aeronautics Law of 2005 defines in its

Article 50 an “obstacle free surface” as the “slanted and horizontal

imaginary planes that extend over each airstrip or airport and its

surroundings, which can limit the height of the obstacles to airplane

circulation. The Aeronautic Authority shall establish in each case

obstacle free surfaces and the maximum height of construction and of any

other type of edification on the properties that, by their nature, may

present a potential risk to airline operations. These provisions

constitute another type of restriction to the property domain, a

geometric form that can be conveniently defined only in

three-dimensional space, and managed with a model with 3D

characteristics.

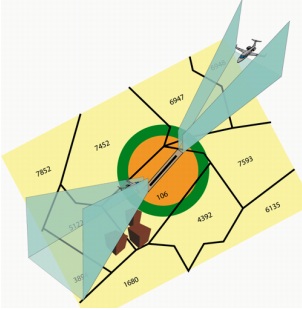

Figure 6 – Aerial space around airports

3.2.5 Urban restrictions

In Argentina these types of restrictions are established by municipal

ordinance and have the goal of fostering coexistence among neighbors,

improving the general welfare and ensuring public health. Some of the

salient features of urban restrictions are the obligation of

noninterference and the lack of compensation for the affected property

owner. Some examples are: chamfered corners (for visibility), building

setbacks, recess of common walls between buildings, land use

regulations, street extensions, etc.

In Brazil, the municipalities regulate the use of urban soil. Given that

the potential for development is defined by the municipality, the air

space in which buildings stand belong to the State, which then

represents a clear and distinct difference between a Right to Build and

a Right to Own Property. This is being discussed by scholars and by the

industries that develop land policy in Latin American cities, and it is

a clear example of the importance of our starting to see the city as an

accumulation of 3D plots on which there is the intersection of private

and public interests.

In Venezuela, the Land Master Plan Law (Ley de Ordenamiento Territorial)

and the Urban Master Plan Law (Ley de Ordenamiento Urbano) (1983 and

1987, respectively, in their Title V), establish that the regulations

derived from the land and urban master plans, drawn pursuant to those

laws by the respective applicable authorities (in particular,

municipalities) impose legal limitations (restrictions) to the property

rights, as they regulate their use and exploitation. In particular,

Article 6 of the Land Master Plan Law stipulates that the plans shall

define for each zone “… corresponding use and regimen, as well as the

definition of volumes and densities” of construction.

4. CONCLUSIONS

While the technologies used to measure, represent, and store information

are now evolving towards 3D platforms, urban legislation and land

policies continue to approach the city as a fat land surface.

To visualize the buildings and the restrictions imposed on properties in

3D is a considerable advancement for those responsible for urban

decision making. Nevertheless, there is a long way to go before 3D

information is integrated as part of urban legislation and property

titles. The consolidation of the 3D cadastre, which registers how 3D

parcels intersect with the corresponding legal norms and regulations,

would contribute to more effective urban and environmental planning,

infrastructure network design; and the prevention of informality by

permitting the construction of future scenarios showing the impact of

land policies in space. Changing the term “area” to “space” would be a

first step in giving urban and environmental legislation a 3D

connotation, and would be a simple and relevant way to start the process

of introducing the new paradigm. The structuring of a 3D property

registry is still under development, but when it is established

landowners will understand that they own cubic feet instead of square

feet.

Hand outs of presentation at FIG Working Week 2012 in Rome, Italy

REFERENCES

Erba, Diego A. (2008) El catastro territorial en América Latina y el

Caribe. 2008. Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. ISBN 978-85-906701-3-1. pg. 415

Available at:

http://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs.

Carneiro, A; Erba, D. & Augusto, E. (2011). Preliminary Analysis of the

Possibilities for the Implementation of 3D Cadastre in Brazil.

Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on 3D Cadastre. Delft,

Netherlands. Available at:

http://3dcadastres2011.nl/.

Lagarda Lagarda Ignacio. (2009). El catastro. Ayuntamiento de

Hermosillo, Sonora, México.

AKNOWLEDGEMTNS

The authors thank these partners and colleagues in the development of

research and publications in this fled of knowledge: Anamaria

Gliesch-Leebmann, Design Concepts 4 You, Seeheim-Jugenheim, Germany;

Andrea F. T. Carneiro, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil;

Eduardo A. A. Augusto, Brazilian Land Registry Institute (IRIB), São

Paulo, Brazil; Ignacio Lagarda, independent consultant on Cadastres in

Mexico; Leonardo Ruiz consultant on Cadastres and GIS in Venezuela; and

Martim Smolka, director of the Program on Latin America and the

Caribbean at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Diego A. Erba

Land Surveyor Engineering (Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina).

Master of Science in Remote Sensing (Universidade Federal de Santa

Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) and Master of Science in Multipurpose

Cadastres (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis,

Brazil). Doctor in Surveying Sciences (Universidad Nacional de

Catamarca, Argentina). He did Post Doctoral research in GIS on Water

Bodies at the Natural Resource Center of Shiga University, Otsu, Japan

and on GIS for Urban Applications at Clark Labs- IDRISI, Clark

University, Massachusetts, USA. Currently, he is a Fellow at the Lincoln

Institute of Land Policy, where he coordinates Distance Education

Programs and manages research projects on cadastres and GIS topics.

Mario A. Piumetto

Land Surveyor (National University of Cordoba, Argentina). Postgraduate

studies in GIS, Remote Sensing and Cartography (University of Alcala de

Henares, Spain). Professor in the Masters in Environmental Engineering

at the National Technological University (2001-present) and in the

department of Labor Final race in Surveying Engineering, National

University of Cordoba (2008-present). Teaching Faculty in the Program

for Latin America and the Caribbean of the Lincoln Institute of Land

Policy (2005-present). He served as Director of the Municipal Cadastre

of Cordoba, Argentina, leading modernization projects in the areas of

Cartography and Land Valuations. Currently, he is a GIS specialist and

independent consultant.

CONTACTS

Diego A. Erba

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

113 Brattle Street,

Cambridge, MA 02138-3400

USA

Tel +1 617-661-3016

FAX +1 617-661-7235

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.lincolninst.edu

Mario A. Piumetto

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba

Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales

Av. Vélez Sarsfield 1.610 – Ciudad Universitaria

FCEFN – UNC – CP 5.000 - Córdoba - Argentina.

Argentina

Tel +54 351 485-5505

E-mail: [email protected]

Website:

http://www.agrimensura.efn.uncor.edu/

|