Enhancing Professional Competence of Surveyors in EuropeStig Enemark and Paddy Prendergast (Ed.) |

||

Professional Competence Models in EuropeDr. Frances PlimmerAbstractThis paper reports on the results of research into the process of identifying professional competence for surveyors within Europe. Against the background of the disciplines identified by the World Trade Organisation and the European Union's Directive on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, the use of mutual recognition as a device for securing the free movement of surveyors throughout Europe is discussed. The role of professional organisations in implementing mutual recognition and the different professional activities of surveyors in different European countries is also presented to improve understanding of both the process of mutual recognition and the way surveyors become qualified in other European countries. Potential barriers to mutual recognition and the advantages of the process, including the culture of surveyors are also discussed. IntroductionThis paper reports on research into how different European countries and their professional organisations assess professional competence for surveyors up to and at the point of qualification. This information is used to develop a methodology to assess professional competence and develop threshold standards of professional competence for the different areas of surveying in order to facilitate the movement of professionals within Europe. Also significant is the existing legislation within the European Union (EU) which ensures the mutual recognition of professional qualifications within this specific region of Europe and the current debate within the World Trade Organisation (WTO) which is developing a similar system of mutual recognition which can be applied world-wide to providers of professional services. Mutual recognition does not affect the ability of an individual to find employment in another country, although there may be some kinds of surveying activities which are restricted to surveyors with certain specific qualifications e.g. licenses. Nor does mutual recognition affect the ability of surveyors to establish their own companies in other countries, although once again, there may be restrictions on the kind of work which is available. Mutual recognition is a device which allows a qualified surveyor who seeks to work in other country to acquire the same title as that held by surveyors who have qualified in that country, without having to re-qualify. Mutual recognition is, therefore, a process which allows the qualifications gained in one country (the home country) to be recognises in another country (the host country). If the content of professional education and training in both countries is similar, mutual recognition should mean that a surveyor's qualifications can be recognised by the relevant professional organisation in another country. Where the content of professional education and training in both countries differ significantly, it should mean that qualified surveyors are required to undertake additional professional education or training (a test or supervised work experience) to gain knowledge which was not part of their original professional education and training in order to have a comparable depth and breadth of professional competence as surveyors who have qualified through the normal process in the host country. The way the EU administers its procedure for mutual recognition is discussed later in this paper. Mutual recognition is perceived by the European Commission as a device for securing the free movement of professionals within the single market place of the EU. For the WTO, the aim is the global marketplace for services, using the process of mutual recognition of qualifications. With these external pressures on surveying professional organisations, it is important that information is available to understand, firstly, how surveyors in different countries acquire their professional qualifications and secondly, the process by which their professional competence is assessed. World Trade OrganisationThe creation of a global marketplace for services is one of stated the aims of the WTO and in recognition of the scale of the task, the WTO has identified mutual recognition agreements (bi-lateral or multi-lateral) as the preferred basis for professions to establish or to extend existing facilities for the free movement of professionals (Honeck 1999). However, bi-lateral or multi-lateral mutual recognition agreements have only limited scope (applying only to those countries who are signatories to the agreement) and may produce a proliferation of different criteria which can confuse and therefore work against the creation of a global market place for services. WTO members have, therefore, agreed to develop specific "disciplines" which can be applied across the entire range of professional services sectors, to ensure that national government regulations dealing with qualification requirements and procedures, technical standards and licensing requirements do not constitute unnecessary barriers to trade in services. Such disciplines aim to ensure that such regulations are:

Part of the outcome of the WTO's Working Party of Professional Services (WPPS) was the Guidelines for Mutual Recognition Agreements or Arrangements in the Accountancy Sector (WTO, 1997) and the Disciplines on Domestic Regulation in the Accountancy Sector (WTO, 1998a). Both the guidelines and the disciplines are general in scope and have the potential to be applied across the entire range of professional services. To date, the WTO has established "disciplines" (WTO, 1998a) which should apply to all services as the basis to secure the free movement of professionals. These are (ibid.):

These disciplines (initially prepared for the accountancy sector) require that any measures ". . . relating to licensing requirements and procedures, technical standards and qualification requirements and procedures are not prepared, adopted or applied with a view to or with the effect of creating unnecessary barriers to trade in . . . services." (WTO, 1998a, at p. 1). The WTO disciplines are deliberately generic because the WTO intends that they should be applied to all services, including surveying. For the purposes of implementing the policy and practice of free movement of professionals, the surveying profession1) has a number of inherent disadvantages.

There is a degree of similarity between the surveying profession, as described above and the accountancy profession, as considered by the WTO (WTO 1998b pp 6-8). For example, the scope and form of accountancy regulation differ widely between countries. There are activities which are regulated in some countries and not in others and activities which may be performed by one profession in one country and by another profession in another country. Regulation of the profession may be at national level or at sub-national level and imposed either by public or private authorities or both (Honeck, 1999 and WTO, 1998b, p 7). The WTO is keen to ensure that these characteristics do not impede any international process which seeks to globalise the provision of professional services. The WTO's proposals have not yet come into force, but provide a background to the research and strong guidance as to how the process of mutual recognition will operate in the future. Of more relevance to this research in Europe, is the existing European Union (EU) legislation on Mutual Recognition of professional qualifications. 1) For the purposed of this research the surveying profession is defined in accordance with the FIG 1991 definition, refer Appendix D. EU Directive on Mutual RecognitionAlthough not applicable to all of the European countries, the requirements of the European Union's Directive on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications (European Council, 1989) cannot be ignored. This Directive applies to all professions for which a specific sectoral directive does not exist. In fact, only a few professions have specific sectoral Directives and these are mainly medical professionals, although architects are also have their own sectoral Directive which means that an architect qualified in any member state is automatically qualified in all EU member states. Thus, the terms of the Directive affect all surveying activities (and therefore surveyors) except where there is conflict with the activities of architects. The Directive is the EU's legal device for securing the free movement of professionals within the Union and applies only to those individuals who hold a three-year post-secondary diploma or equivalent academic qualification. Despite the fact that this research covers the whole of Europe, the relevance of the EU's Directive is significant. It will be difficult (if not impossible) for independent professional organisations to establish a single methodology and procedure to secure professional mobility which does not reflect the legal requirements of at least part of the jurisdiction involved. Thus, the presumption is made that the "surveyor" is not only a professional (i.e. a practitioner of surveying activities) but also a holder of an appropriate academic qualification. The Directive does not, however, require that the diploma held must be within the same academic discipline as the profession undertaken, merely that the diploma must prepare the individual for the profession. Thus, it is possible to hold a diploma in an academic discipline which is unrelated (or of limited synergy) to the profession undertaken, provided such a diploma is recognised to have prepared the individual for the profession. The EU's Directive requires either:

The Directive was adopted in order to ensure the free movement of "professionals". However the terms of the Directive can be interpreted as defining the "professional" as someone holding either a profession-specific diploma (without any additional professional experience) or a diploma (not necessarily profession-specific) plus at least two years of professional experience. For the purposes of the Directive, the French interpretation of "professionelle", meaning "vocational", is adopted. Thus, the Directive does not imply a level of professionalism, it merely permits applicants to sign up to a code of professional conduct if one is required of a member of a professional organisation to which they have applied. Thus, to benefit from the terms of the Directive, a surveyor should be a practitioner, with a three-year diploma awarded by a competent authority in one of the EU's member states. For most surveying activities in most countries, it is evident from this research (refer later) that only a surveying-specific academic diploma gives access to the surveying profession. However, this is not universally true. There are aspects of surveying for which a diploma in, say law or economics, will give access to surveying employment which itself provides appropriate education and training to produce the qualified surveying professional (Gronow & Plimmer, 1992). In member states where it is necessary to hold a licence in order to practice as a surveyor, it is for the licensing body to request academic organisations in each member state to provide details of the content of academic education which is required for access to their surveying professions. However, it is for the licensing body to make the decision as to the appropriateness of the nature and content of the applicant's professional qualifications. There is no requirement under the terms of the Directive that the academic education required prior to qualification should comprise specific subject matter. All that the Directive requires is a comparative assessment of the relative content, depth and length of professional education and training of the "migrant" as compared with that required of a surveyor newly-qualified in the home member state. The EU Directive recognises the equivalence of knowledge acquired through an academic diploma and knowledge acquired though supervised work experience. Thus, no distinction is made if a particular body of knowledge which is absent from the academic diploma held by a "migrant", is acquired through specific work experience and the adaptation mechanisms which allow a "migrant" to make good any apparent deficiencies of academic or pre-qualificational knowledge, can be either an aptitude test (examination) or an adaptation period i.e. a period of supervised work experience. It is not considered appropriate that any recommended methodology should include specific consideration of the academic education of the individual, nor is it considered essential for all surveyors to belong to a professional organisation in their home countries (although the failure to belong to a professional organisation where one or more such appropriate organisations exist in the home country may indicate an absence of a suitable level of professional competence). Thus, although not necessarily a member of a surveying professional organisation within the home country, the surveyor who can benefit under the terms of the Directive from free movement within the EU member states and whose professional competence requires assessment is both:

From the point of view of implementing the terms of the Directive, it is necessary to understand how surveyors acquire their professional qualifications, both the academic and the post-academic processes. The nature of the procedures and processes of national recognition of surveyors is well-established in each country, but not generally well-understood by other countries' surveying professional organisations and one of the main aims of this research is to improve understanding of how surveyors in different European countries acquire their professional status as a basis for establishing the free movement of surveyors. However, before considering the methodology for assessing professional competence as a basis for securing mutual recognition of professional qualifications, there are a number of issues which need to be discussed. Surveying Activities and Surveying ProfessionsSurveying, as a profession, has developed in different ways and encompassing different surveying activities in different countries, in order to reflect the national needs which have developed over time. Thus, while a similar range of surveying activities may be undertaken in different countries, there may be differences between the way these activities are grouped as a recognised "profession". For example, in the UK, the activities of urban property agency, development, management, planning and valuation are grouped as "general practice surveying" for which there is a recognised academic and professional qualification and title (Chartered Valuation Surveyor), and thereby these professional activities comprise one profession. Such activities in France are traditionally shared between four professionals - the agent immobilier, gérant, expert immobilier and the conseil juridique (Plimmer, 1991). Similarly, the content of surveying education and the way it is structured differs throughout Europe and this is graphically demonstrated in Professor Mattsson's paper elsewhere in this report (Mattsson, 2001). It is unreasonable to expect every country to alter the nature of its surveying profession or its surveying education, unless its own national consumer or professional interests are served by such changes. Indeed, there are huge dangers in attempting to harmonise professional education across a large number of countries. Previous experience within the European Community in establishing a single sectoral Directive for Architects, which involved the harmonisation of their academic education across all of the then member states, took 16 years to achieve and every change in academic content requires renewed negotiation (Plimmer, 1991). The implications of the EU directive and the WTO proposals are that it does not matter how individuals achieve professional status, the important point is that they have achieved professional status. The only reason to investigate the nature and content of their pre-qualification process is to identify any discrepancy between the professional education and training of the "migrant" with that required of a newly-qualified surveyor in the host country and therefore to establish an adaptation mechanism to make good the deficiency. However, for free movement to take place between member countries, there must be, what the Directive described as, a corresponding profession i.e. a substantial similarity between the surveying activities involved in the surveying professions in both the home and the host countries This is a matter for the professional organisations in each country to establish and monitor, as is the professional content of any adaptation mechanism required. In the light of the terms of the EU directive and the implications of the WTO proposals, the ability of surveying professionals to work in other countries must depend on:

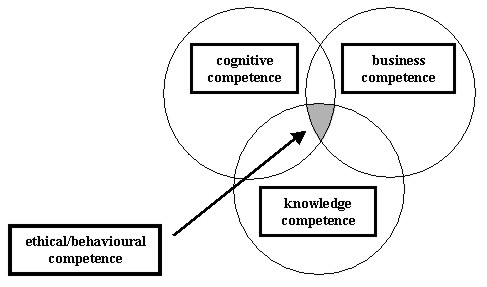

Thus, it is necessary for the surveying professional organisations in each European country to identify which surveying activities are comprised within their surveying professions and which are therefore required of any surveyor who wishes to practice that kind of surveying profession in that country. Comparing such a list of surveying activities with those with which the surveying applicant is qualified and experienced, also provides the host-surveying organisation with details of those areas of professional competence which the applicant is lacking. According to the EU Directive, such deficiencies can be remedied by either by an aptitude test (examination) or a period of supervised work experience. Professional organisations in each country should consider appropriate, practice-based tasks which can demonstrate that an applicant has made good any deficiencies in professional education and training and is competent to practice as a surveyor both in the host country and as a member of the host professional organisation. The role and responsibilities of professional organisations in the process of mutual recognition of professional qualifications is considered in detail later in this report. Professional CompetenceEffectively, what is required by the WTO disciplines and the EU Directive is an assessment of the professional competence of an applicant (called a "migrant" in the EU Directive). According to the current interpretation of the Directive, the standard against which that professional competence should be assessed is that required of a newly qualified surveyor in the host member country. It is therefore a major function of this research to assess what pre-qualificational professional competence is required of a surveyor in each European country and this has been extended to include an investigation of the process through which surveyors gain their qualification - including academic diplomas, professional work experience, licensing procedures and/or membership of a professional organisation. The relative processes are discussed later in this report. Despite the fact that it is the professional competence of the surveyor which is fundamental to the ability to practice freely across national boundaries, it is interesting to consider certain characteristics of the surveyor as an individual. Thus, it is noted that the definition of a surveyor, as agreed at FIG's General Assembly in Helsinki, Finland on 11 June 1990 (FIG, 1991 p 9), is ". . . a professional person". "Professional competence" is extremely hard to define, although it is something with which all surveyors are familiar. It is suggested (Kennie et al., 2000) that for newly-qualified surveyors in the UK, "professional competence" combines knowledge competence, cognitive competence and business competence with a central core of ethical and/or personal behaviour competence. Thus:

Source: Kennie, et al. 2000 p. 2 Kennie et al. (ibid. Appendix B pp. 8-9) have defined these component parts of professional competence, as follows:

It may be that for each surveying profession in each European country, the relative weighting of such components may differ but it is contended that these four competencies comprise the essence of "professional competence" for surveyors everywhere. It is axiomatic that the individual whose competence is being assessed is a fully qualified professional in the European Country where the professional qualification was gained (i.e. the home country). However, it is that individual's competence to work in another European Country (the host country) which needs to be assessed. Thus, for the purposes of facilitating professional mobility, it is necessary to recognise and accept the professional status and the competence of the applicant in the home country. For the professional organisation in the host country it is necessary merely to ensure that the applicant is competent to undertake surveying, as practised in that host country and therefore to ensure that the applicant is fully aware of and has adapted to the nature and practice of the surveying profession in the host country. Therefore the professional organisation in the host country needs to establish the nature and level of professional competencies within a range of surveying activities required of a fully-qualified professional in the host country and to assess the applicant against that content and standard of professional competence. For example, The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) which is one of the UK's professional organisation for surveyors, has a list of competencies at different levels required of newly-qualified surveyors as an objective basis of comparison (RICS 2000) which is compiled for its APC (Assessment of Professional Competence) and this is discussed later. What is ignored within the current interpretation of the Directive is the fact that the individual being assessed for this purpose is both a professional in the country which awarded the original surveying qualification and a practitioner. Thus, there is no recognition of the elements of specialisation or expertise which an applicant may have developed over a number of years practice, and it is both the level and the areas of knowledge and skill required of a newly-qualified surveyor in the host member country which an applicant must demonstrate to the competent authority. It is suggested that it is for the professional organisation in the home country to assure other professional organisations of the professional standing of applicants. This should include such matters as the nature of the surveying profession pursued by the applicant and their component activities, the level of the applicant's professional qualification and statements regarding any action taken by the professional organisation against the applicant for disciplinary offences. Once this has been done, it is not for the professional organisation in the host country to challenge the status and professional integrity of the applicant. Their role is merely to establish that the applicant has achieved the appropriate level and range of skills required in the host state, as set out in an objective list of threshold standards, including (presumably) that the individual has become fully conversant with and is prepared to observe the professional ethics and codes of practice it requires. Role of Professional OrganisationsAs indicated above, there is a major role for the professional organisations which award surveyors their surveying qualifications in the process of mutual recognition. It is recognised that there are different roles undertaken by professional organisations. Indeed, for the purposes of this research, it is appropriate to define the term "professional organisations" by their function or functions rather than by their names. Thus for the purposes of this research, "professional organisation" means those organisations at national or sub-national level which:

In some countries, there is more than one "professional organisation" as defined above. For example, in Denmark, cadastral surveying can only be undertaken by surveyors who have a masters-level diploma (bac + 5), who have undertaken relevant professional work experience and who have been granted a license by the National Survey and Cadastre (under the Ministry of Housing) (Enemark, 2001). In the United Kingdom (UK), The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) assesses the quality of academic education through its system of accrediting diplomas (bac + 3), and implements a system of assessing relevant professional work experience (there is no licensing system for surveyors in the UK). It is also recognised that in some European member states, some of these functions are undertaken by government ministries e.g. the French préfet awards the carte professionelle license. In order to achieve the free movement of professionals, judgements need to be made on the nature of the individual's professional qualification and experience which is gained in the home country in the light of the nature of the profession as practised in the host country. Thus, the organisation to which the individual applies for recognition in the host country needs sufficient information, firstly, to recognise the nature, scope and quality of the professional qualification held by the individual and, secondly, to verify its accuracy. This requires a high level of effective and efficient communication from the professional organisation in the home country to the professional organisation in the host country which includes:

Ideally, this should be based on a simple questionnaire which could be sent (via e-mail) to the relevant organisation which should have a standardised procedure to ensure both accuracy and speed of response. There should be sufficient information, available in the public domain, to ensure appropriate understanding of the responses received, which may not always be in the language of the host country. Thus, a vital role of each professional organisation is the provision of information relating to the nature of professional qualifications, the nature of the various surveying professions for which each is responsible, a database and a procedure which allows a rapid and accurate response to requests for information about particular individuals. Also, each professional organisation should also have a procedure which requests and deals with requests for the above information and processes them, together with the applicant's request for mutual recognition, in an efficient and effective manner. Ultimately, it will be for the professional organisation to establish what, if any, additional professional education and/or training is necessary before a particular applicant is able to practice within the host country in the light of the threshold standards applied to newly-qualified nationals. However, there is a problem of requiring an experienced practitioner to demonstrate the same breadth of professional skill and knowledge over the range of threshold standards required of a newly qualified surveyor in the home country. During the course of a professional career, it is not unreasonable to expect professionals to develop high levels of expertise in some areas at the expense of others. It may be extremely difficult (and certainly daunting) for such practitioners to acquire and demonstrate the full range of skills required of a newly qualified national in the host country. It is, therefore, suggested that, in the light of the implicit professionalism of the applicant and the recognition of the distinction between the nature of the surveyor's competence at the point of qualification and subsequently during (what for some is) a long and varied career, a pragmatic approach should be taken which ensures that the applicant can demonstrate the adaptation of existing surveying skills to a new working environment (including perhaps new ethics and codes of practice), together with a broad understanding of the other surveying activities and issues which affect the profession in the host member country. However, it is likely that, with the aim of being seen to maintain high quality of services and products, the most contentious issues for surveyors and their professional organisations will not be the comparability of professional activities, or the level and scope of professional education and training, but the exact nature of the compensatory measures required which must be left to the professional organisations concerned to consider. Thus, the role of professional organisations is vital if free movement of professionals through the mutual recognition of qualifications is to be achieved. Barriers and HurdlesAlthough not of direct relevance at present, the potential impact of the WTO disciplines as a device for achieving mutual recognition of qualifications and thereby free movement of professionals and the EU's Directive on mutual recognition have informed this discussion. The inevitability of WTO legislation to ensure the free movement of surveyors on a global basis is assumed, as is the presumption that if a methodology can be established within a European context, such a methodology can be applied world-wide. This does not, however, mean that the process will be easy, either in theory or in practice. There are major issues of principle (not the least of which is that of mutual recognition itself) which professional organisations on behalf of their own countries need to embrace and embrace with commitment. However, professional organisations are frequently held back by bureaucracy and by a potential conflict of views between ministry rules with which professional organisations do not always agree. Thus appropriate ministries should be included in any discussions on mutual recognition processes. Certain principles will cause great difficulties. It is suggested, for example, that the apparent equivalence (according to the EU Directive) of academic testing and professional practice and experience to make up any deficiency in professional knowledge will challenge traditional professional education principles. There are, however, a number of principles which should be observed, and these include the absence of any form of discrimination against any individual surveyor simply because qualification has been earned in another country. Indeed, this is a requirement within the WTO disciplines proposed (WTO, 1997 and 1998a). Assuming that the professional organisations which represent surveyors and which monitor their qualifications fulfil their responsibilities fairly and professionally, there should be little problem in administering the process of mutual recognition of qualifications. Similarly, it will be necessary to ensure that practising licenses, which are normally awarded to those professionals who have achieved an appropriate level of academic (or academic and professional) qualification and who are required to demonstrate often to a government-appointed authority, the quality of their professional practice skills, are awarded solely on the basis of professional competence to practice in that country and not on any basis which discriminates against those who are professionally training and experienced in another country. It seems that in some countries where the award of a practising license is required, only those holding certain qualifications are permitted to apply. Again, provided that no distinction is made by the licensing authority between those applicants whose qualifications were gained in the host country and those who have acquired their qualifications by a process of mutual recognition, that all are required to undergo a similar process and demonstrate similar levels of professional competence in order to acquire practising licenses, there should be no unreasonable barriers to the free movement of professionals. However, it is recognised that we are all products (to a greater or lesser extent) of our national and professional backgrounds and the various cultural influences which affect how we work and why we undertake our professional activities in the way we do. In order to achieve any kind of dialogue, these differences, particularly those in professional practice, and those which affect inter-personal relationships, need to be investigated, understood and respected. The most obvious barrier to the free movement of surveyors is language, but access to learning different languages is normally dependent on individual opportunity and effort, and, initially, on national primary and secondary education systems which can provide either a very positive or rather negative lead. Language skills are, however, vitally important to permit international communication and genuine understanding of the rich variety of professional and personal life-styles. As such, it is a barrier which can be overcome, although it is suggested that the real "language" barrier will be in establishing the technical meaning of the educational and professional jargon e.g. the meaning of "diploma" in continental Europe is not the same as that used in the UK and in Ireland. However, there is also the matter of culture which permeates our national or regional societies and which comprises a series of unwritten and often unconscious rules of conduct, professional practice and of perceived relationships. Failure to understand and observe the cultural norms of other people can result in confusion, hurt and, at worse, perceived insult, and there is evidence that culture divides us, both as individuals (as the products of our nation's upbringing) and also as surveyors (as the products of our professional background). Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997), in a work which illustrates that many management processes lose effectiveness when cultural borders are crossed, describe the nature of specific organisational culture or functional culture (ibid. pp 23-4) as ". . . the way in which groups have organised themselves over the years to solve the problems and challenges presented to them." Based on the historical and original need to ensure survival within the natural environment, and later within our social communities, culture provides an implicit and unconscious set of assumptions which control the way we behave and expect others to behave. Thus, "The essence of culture is not what is visible on the surface. It is the shared ways groups of people understand and interpret the world." (ibid. p 3), and as surveyors, although we all perform similar functions and provide similar services to our clients, we achieve these by different means. This paper contends (as do Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997)) that the fact that we use different means is irrelevant. What is important is that we perform similar functions and provide the services professionally (efficiently, effectively and within an ethical context) and to the satisfaction of our clients. However, to ensure the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, cultural differences need to be recognised in order to understand and accept that surveyors in different countries have different perceptions as to the nature of professional practice and the routes to professional qualifications. The research has identified discrepancies between the professional activities undertaken by different kinds of surveyors in different European countries, with some kinds of surveying activities demonstrating a greater or lesser degree of international commonality (refer later). It is contended that there is nothing wrong with difference, it merely has to be recognised and accommodated within whatever system is devised for the creation of the free movement of professionals. Threshold Standards of Professional Competence for the Different Areas of SurveyingThreshold standards are those academic and/or professional qualifications required of a newly qualified surveyor. They can be identified by reference to such achievements as a particular academic award, a period of professional work experience, the holding of a licence or membership of a professional organisation and, for the purpose of comparison between different countries, should be defined by reference to the professional competencies which the "qualified" surveyor has achieved. It must be recognised that, in some countries, there are different kinds of surveyors whose professional education and training follows different routes and therefore for the purposes of this research, it is necessary to investigate the professional competencies for each kind of surveyor in each European country. However, threshold standards of professional competence for the different areas of surveying cannot be investigated until certain other issues have been identified. Thus, it is necessary to identify for each European country:

It is likely to be a requirement that all applicants hold either a diploma in a relevant surveying profession or a diploma which gives access to the surveying profession in their home country (see above). Most of the issues cited above require the provision of factual information from professional organisations in European countries. There are two main issues which need to be discussed. Professional Competence of a PractitionerWhile it may be relatively straightforward to identify the professional activities and level of knowledge and skill required of a newly-qualified surveyor, it is very different to assess the appropriate breadth and depth required in the knowledge and skill of an experienced practitioner. It is suggested that very few professionals (if any) retain and maintain the original level of skill and knowledge across the full breadth of professional activities which is normally required at the time of qualification. It is not unusual for surveyors to begin their professional careers by experiencing different kinds of professional activities before specialising in a limited range of professional activities and it is hypothesised that the majority of surveyors specialise in one or several areas of professional practice which then become the focus of their careers. While some organisations may require practitioners to keep up-to-date on changes affecting areas of professional practice, it is not reasonable to expect surveyors to maintain the same breadth and depth of knowledge as that achieved on qualification. Levels of expertise in some areas are matched by levels of relative ignorance in others, particularly in new developments in those areas. Surveyors remain "competent" because they work within their areas of expertise and do not undertake work for which they do not have sufficient up-to-date knowledge and skill. Indeed, they would be negligent and unprofessional were they to do otherwise. Thus, the practitioner whose competence is being assessed in another member country, is likely to be an experienced practitioner in a range, but not in all, of the areas of professional practice which comprise the surveying profession in the home country, and it is as an experienced professional that the applicant should be assessed. However, the current interpretation of the Directive expects the applicant to demonstrate a full range of knowledge and skill across all aspects of the surveying profession as practised in the host country which can, therefore, be measured against the list of competencies required of a newly qualified surveyor. It is contended, however, that this approach discriminates against the more mature and experienced migrants for whom it should merely be necessary to establish that, within the areas of expertise in which they are experienced and in which they practice, they are competent to undertake those professional activities in the host country and that they are aware of the broader issues which affect the profession of surveying in the host country. In other words, it should be necessary merely to ensure that, as a surveying professional with a range of expertise, the applicant has adapted that range of expertise to a foreign working environment and is therefore "competent" to practice in the host country and to acquire the relevant surveying title and/or qualification. Current interpretation of the Directive, however, requires that all migrants are assessed against the standard applied to a newly qualified surveyor in that member country, and therefore it is vital to investigate the threshold standards applied to newly qualified surveyors in Europe. Professional Nature of PractitionerThe concern for competence is generally considered to be that of the professional organisation and the other surveyors in the host country. It is certainly likely to be the responsibility of the host country to assess the professional competence of the applicants. However, it is suggested that the applicant too is concerned to demonstrate competence, not merely to secure the title or qualification of the host country, but also because of the high moral code of conduct required of a professional within Europe. Historically, the nature of a "professional" implied high moral conduct and provided a standard of service on which the public and governments relied to ensure socially correct and ethical behaviour. Recently, professional organisations impose codes of conduct on their members, and it is the resulting level of conduct and moral behaviour which provides the very core of the status accorded to professionals (refer Kennie, at al. 2000). However, it seems that it is not always possible to rely on professionals to behave in an ethical manner and therefore, professional organisations have a responsibility to ensure that professionals are competent and remain so. The external imposition of ethical behaviour is particularly important for employees who may be forced to undertake a particular professional activity as part of their employment for which they have not received adequate education or training. UK Experience of Mutual Recognition procedureIt must be recognised that the applicant seeking to move from one European country to another is a fully qualified professional and cannot be expected to re-qualify in another country. Indeed, the principles of mutual recognition of qualifications specifically seek to avoid this. Thus, for the purposes of mutual recognition, it may be that requirement (d) above is superfluous. Experience in the UK since the introduction of the terms of the Directive and the various reciprocity agreements entered into by The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors show that, without exception, all applicants have obtained employment within the surveying profession in the UK and have sought to adapt their existing professional expertise to the conditions and practice within the UK. Difficulties have arisen where the nature of the profession as practised in the UK differs from that practised in the home country and adaptation mechanisms have been imposed. However, it has been necessary to require the applicants to demonstrate the breadth and depth of knowledge within their chosen areas of expertise as well as in other professional activities which comprise the particular kind of surveying profession in question. However, what is suggested is that the professional profile of each applicant should be considered in the light of the totality of the academic and professional education, training and experience gained in the home or any other EU country as at the date of application. A comparison can then be made between this level and degree of professional competence and:

Where an applicant does not have the necessary knowledge and skill to undertake a relevant professional activity, an appropriate adaptation mechanism, either supervised work experience or an examination, can be required. It should be noted that the EU directive does not permit competent authorities to require an examination as the adaptation mechanism for surveyors. Having been required to remedy a deficiency in certain areas of professional activities, the applicant surveyor is free to choose whether to do this by supervised work experience or by undertaking an examination. In order to achieve consistency and to avoid any legal conflict, and in the light of WTO's recognition of the equivalence of education, experience and examination requirements, it is suggested that a similar approach is adopted i.e. that the applicant can choose between either an examination or a period of supervised work experience. In either case, it must be possible for an applicant who does not achieve the appropriate level of competence to fail. Threshold Standards in EuropeIn order to identify threshold standards applied to surveyors in Europe, a questionnaire was devised and distributed to attendees at the joint CLGE/FIG seminar in Delft 2) . The questionnaire which was piloted at the Delft seminar and amended subsequently, sought to identify issues of comparability in the nature of the work of geodetic surveyors in Europe, the nature of their academic and professional pre-qualification process and to identify any threshold standards applied to newly-qualified surveyors. 2) Enhancing Professional Competence of Geodetic Surveyors in Europe a joint CLGE/FIG seminar held in association with the Department of Geodesy, Delft University of Technologu, 3rd November 2000. Analysis of QuestionnairesThe questionnaire distributed to the delegates at the Delft seminar is included with this paper. The response rate was 51%, covering 16 of the 20 countries (only Italy, Latvia, Norway and Slovenia are omitted). 1. Professional ActivitiesIn investigating the activities which surveyors in Europe undertake, the FIG definition (FIG, 1991) was used because it is a widely used international definition in languages other than English. The analysis revealed that, with the exception of Belgium and Luxembourg, all surveying respondents considered the following to be the activities of surveyors in their countries: (1) the science of measurement; Practice of the surveyor's profession may involve one or more of the following activities which may occur either on, above or below the surface of the land or the sea and may be carried out in association with other professionals: (5) the determination of the size and shape of the earth and the

measurement of all data needed to define the size position, shape and

contour of any part of the earth's surface; Belgium excluded (5) (the determination of the size and shape of the earth and the measurement of all data needed to define the size position, shape and contour of any part of the earth's surface); (6) (the positioning of objects in space and the positioning and monitoring of physical features, structures and engineering works on, above or below the surface of the earth); and (8) (the design, establishment and administration of land and geographic information systems and the collection, storage, analysis and management of data within those systems). Luxembourg also excluded (4) the instigation of the advancement and development of measurement etc. practices With regard to the other activities ((9) the study of the natural and social environment, the measurement of land and marine resources and the use of the data in the planning of development in urban, rural and regional areas; (10) the planning development and redevelopment of, whether urban or rural and whether land or buildings (11) the assessment of value and the management of property, whether urban or rural and whether land or buildings; (12) the planning, measurement and management of construction works, including the estimation of costs), Belgium, and Luxembourg together with Ireland excluded (9) the study of the natural and social environment, the measurement of land and marine resources and the use of the data in the planning of development in urban, rural and regional areas; although responses from the Netherlands were contradictory. The Czech Republic, Spain, Ireland, and Luxembourg, excluded (10) the planning development and redevelopment of, whether urban or rural and whether land or buildings and, once again, responses from the Netherlands were contradictory. However, only France, Greece, Luxembourg, Sweden and the UK included (11) the assessment of value and the management of property, whether urban or rural and whether land or buildings; and only Austria, France, the Slovak Republic, Switzerland and the UK included (12) the planning, measurement and management of construction works, including the estimation of costs. Once again, the responses from the Netherlands were contradictory. Additional activities mentioned by respondents included photogrammetry and remote sensing (Spain, Greece, Slovak Republic) with the Czech surveyors responsible for the standardisation of names of settlements; the Spanish surveyors responsible for geophysical prospection and industrial applications of surveying; the Greek surveyors including road planning and hydraulic work and the Slovak Republic including geodynamic monitoring. The UK also include property investment analysis and portfolio management as an activity related to (11) the assessment of value and the management of property, whether urban or rural and whether land or buildings; and the planning and implementation of the repair, maintenance and refurbishment of existing buildings, which is an activity undertaken by building surveyors. It should be pointed out that in the UK although all of the surveying activities listed are practised by surveyors, those surveyors qualified to do activities (1) - (8) (land or geomatic surveyors) are not also qualified to undertake work in the other areas. Similarly, the qualification of the quantity surveyor or construction economist (12) does not include any of the other activities (except for the production of plans, reports etc. (13)); and the qualification of general practice surveyor or valuation surveyor (11) does not include other activities (except for (13)). Thus, while all of the activities are practised in the UK by surveyors, the professional activities and therefore the academic and professional education and training, differs between some seven different kinds of surveyors and it is not usual for a surveyor to be qualified in more than one specialisation. In summary, it seems that the activities of (11) the assessment of value and the management of property, whether urban or rural and whether land or buildings; and (12) the planning, measurement and management of construction works, including the estimation of costs are those which are least common throughout the respondent countries, with widespread commonality regarding the various surveying activities of land measurement and management. 2. Regulation and LicensingThere is evidently a variety of regulatory and licensing arrangements in the countries surveyed. Some countries e.g. Luxembourg, Netherlands and Sweden reported no regulatory organisations and France, Ireland, Luxembourg, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the UK reported no licensing organisation. In Germany, both regulation and licensing are a function of the government at state-level. It should be noted that although the UK recognised The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) as a regulatory organisation, there is no control over surveyors and surveying activities in the UK. The RICS merely controls the title of "Chartered Surveyor" but there is no legislative requirement in the UK for any kind of surveying activity to be undertaken by a Chartered Surveyor. 3. Academic EducationThere is a predominance of bac+5 as a prerequisite for entry into the "Ing" level of the surveying profession after tertiary education. Only the UK reported an entry level as low as bac+3. Ireland requires bac+4 as do two Hogeschools in the Netherlands. Sweden requires bac+4.5. In the light of the breadth of professional activities for which these students are educated and trained, it is not surprising that the academic education lasts for five years. The comparatively narrow and specialist nature of UK academic surveying education perhaps explains the bac+3 process. 4. Additional RequirementsOnly Belgium, Spain, Greece, the Netherlands and Sweden reported no requirement for post-university work experience prior to qualifications. The duration of such work experience for those countries which required it ranged from one year (Switzerland) and five years (Slovak Republic), with two or three years being common. Only Austria, Greece and the Slovak Republic required membership of a professional organisation, while the Czech Republic, Luxembourg and Switzerland required the taking of a state examination. Six countries reported a limit on the nature of work undertaken by pre-qualified surveyors and this relates almost entirely to their inability to undertake cadastral work. 5. Threshold StandardsAlthough it was recognised that the requirement to hold a certain academic qualification and/or pass a state examination were "threshold standards", only the UK, through The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors imposes specific threshold standards after the award of a bac+3 accredited University degree and two years of supervised work experience. These threshold standards, which the RICS calls "competencies" are explicitly documented and specifically tested during the surveying applicant's supervised work experience by the employer and at the point of qualification by the RICS in its Assessment of Professional Competence. These competencies vary for the different divisions or specialisms of the RICS and are divided (RICS, 2000) into:

Each of these competencies (and those specified for the other specialisms) are defined (ibid.) in relation to three levels. Thus, Cadastre is defined (ibid. p. 17), thus: "Level One- define field and office procedures for boundary surveys, identify legal and physical boundaries and provide evidence of boundaries. "Level Two- demonstrate an understanding and related use of the principles of land registration and legislation related to the rights in real property. Understand the surveyor, client and legal profession relationship and the preparation of evidence for the legal process. "Level Three- demonstrate a full appreciation of the activities and responsibilities' / of the expert witness. Understand the resolution of disputes by litigation and alternative procedures." Thus, a Geomatics candidate for the Assessment of Professional Competence, could choose to demonstrate competence in level one or level two Cadastre as one of the optional competencies; or level three Cadastre as a Compulsory Core Competency. Alternatively, a Geomatics candidate can choose to demonstrate other competencies and avoid Cadastre altogether. This process relies heavily on the employer, firstly to ensure that the candidate is experienced in the appropriate range and level of competencies and, secondly, to certify that the candidate has gained the appropriate standard in each competency. The additional requirements of the Assessment of Professional Competence, including a written submission and presentation, diary and log book and interview, give the RICS's Assessors the opportunity to verify the candidate's achievements. The process is monitored by the RICS, employers are supported by specialist advisors and APC Assessors (qualified and experienced surveyors) are trained to ensure uniformity and quality of testing. The very uniqueness of this system in the UK justifies the detail with which it is presented here. As a statement (or series of statements) describing the professional activities of surveyors, it is extremely useful, and demonstrates a device for ensuring and testing professional practice as an alternative to academic-style examination at the point of professional qualification. However, it can be argued that, as a process, it is flawed. It is highly mechanistic and it places huge responsibilities on employer practitioners who are encouraged, (but not required), to provide structured professional training, supervision and counselling for their graduate employees. Employers are not trained in this educational role (although there is access to a Regional Training Advisor for assistance), nor is any sanction imposed on the employer if the quality of training and/or assessment is inadequate. In principle, the combination of academic education and professional training should be appropriate for qualified surveyors and many countries in Europe require such a process. However, the research has demonstrated a range of processes for acquiring professional status, from the holding of an academic qualification only (e.g. Spain and the Netherlands) to a mixture of academic education and professional experience (e.g. Czech Republic and Denmark). Some countries include a requirement to belong to a professional organisation (e.g. Ireland and Switzerland) and some add a licensing system (e.g. Austria and Slovak Republic). Such information is vital if we are to understand how surveyors acquire their qualifications and therefore understand how mutual recognition can work in Europe. Mutual recognition of professional qualifications is not a reason for any country to change the way its surveyors acquire their professional qualifications, although we can benefit from understanding the systems and processes adopted by each other. Methodology for Professional OrganisationsIt should be evident from the earlier discussions in this paper, that there is a role for professional organisations and specific actions which such organisations should take in order to ensure effective and efficient free movement of professional surveyors world-wide. The underlying issue of mutual recognition is not the awarding of qualifications from other countries, but the rights to practice one's professional skills in those other countries. The awarding of qualifications (and the right thereby to apply for appropriate licenses) is merely a device for ensuring that only appropriately qualified individuals have access to regulated professional activities. Professional OrganisationsIt is recognised that, throughout the world, there are different roles undertaken by professional organisations. Indeed, for the purposes of this paper, it is perhaps appropriate to define the term "professional organisations" by their function or functions rather than by their names (refer above). In some countries, there is more than one "professional organisation" as defined above. For example, in Denmark, surveyors gain professional qualifications from the Den danske Landinspektørforening but a license to practice is awarded by the National Survey and Cadastre (under the Ministry of Housing). In the Ireland, The Society of Chartered Surveyors fulfils all of these roles (there is no licensing system for surveyors in the Ireland). The following considers each of these roles which professional organisations currently undertake and discusses their relevance to mutual recognition.

3. Regulate the conduct and competence of surveyors:

Professional associations range from strictly government bodies to completely private organisations. Their activities may encompass any or all of a wide range of functions, including examinations and authorisations, education and training, professionals standards, disciplinary measures, quality control, providing various membership services and representing the profession. They can represent their members at local, national, regional and international levels. Similarly, the legal forms for the practice of activities, licensing and professional qualification requirements vary, although the underlying reasons for such controls, e.g. to ensure liability and prevent conflicts of interest, consumer protection, respect of relevant laws and regulations, remain the same. Other common requirements relate to professional education and training, indemnity insurance, absence of a criminal record, proof of membership of a professional organisation, residency and citizenship requirements. Under the EU Directive (and potentially under the WTO disciplines) the most contentious issues for professionals and their professional organisations (such as comparability of professional activities, level and scope of professional education and training, the exact nature of the "compensatory measures" required) are left to the professional organisations concerned to consider and yet for most professions and their members, these are likely to be the most important issues of all. Thus, the role of professional organisations is vital if free movement of professionals through the mutual recognition of qualifications is to be achieved. ConclusionsMutual recognition does not require any country to change the way its surveyors become qualified - either in terms of the process or the standards which should be achieved. It does, however, require that we recognise qualifications gained from other countries using other processes. Yet, it is not the process of achieving qualification which is tested, nor should it be. It is the quality of the outcome, measured against objective national criteria (threshold standards) which determines whether a surveyor from one country has the appropriate professional education and training to practice in another country. There are a number of barriers which hinder mutual recognition in Europe. Language, national customs and cultures are, however, not true barriers to mutual recognition and the free movement of professionals which mutual recognition is designed to achieve. Ignorance and fear are the main barriers and yet with improved communication and understanding, these will disappear. Indeed, as surveyors, we do have a number of very real advantages to achieving free movement. Firstly, it is something which has been recognised as important to our profession. As an international group, both the CLGE and FIG have recognised its importance by the commissioning of this research and by the establishment of the FIG Task Force, the aim of which is to consider ". . . a framework for the introduction of standards of global professional competence . . " looking specifically at mutual recognition and reciprocity, in order to ". . . develop a concept and a framework for implementation of threshold standards of global competence in surveying." (FIG, 1999). Secondly, we have a proven record of being able to negotiate international standards of professional practice. For example, the creation and adoption of the so-called Blue Book of European standards of valuation (refer, for example, Armstrong, 1999) has created a uniform standard for valuation practice within the region of Europe. The creation of the so-called Blue Book is the result of decades of international negotiation by valuers and has, inevitably, been the subject of up-dating and amendment. Such co-operation on an international scale is demonstrated by the International equivalent (the so-called White Book) which is the result of the efforts of the International Valuation Standards Committee (IVSC 2000). Thirdly, we have a universal definition of "surveyor" (FIG 1991) which is capable of being up-dated to reflect changes in the evolving nature of our professional practices and skills. We may group these professional skills in different ways in different countries, we may use different terms to describe our skills, we may have greater need for particular kinds of surveying skills in some countries compared to others, but, broadly, as surveyors, we have a very clear idea about what services we offer to the public and our employers. What we do not have is:

Nevertheless, if we concentrate, not on the process of becoming a qualified surveyor, but on the outcomes of that process, then much of the above cease to be any real barrier to the free movement of professionals. Mutual recognition, either as a profession world-wide or on a more selective reciprocity basis, becomes simply an issue of investigating the competence of qualified individuals to perform the surveying tasks undertaken in other countries. It is contended that no attempt should be made to impose a uniform system of professional education and training on surveyors. It has been demonstrated that such harmonisation is a lengthy and detailed process which continues long after initial agreement has been reached, as the profession develops. Free movement should be achieve by respecting the outcome of the professional education and training processes throughout the world and by considering the nature and level of competence of surveyors rather than the process through which they achieved their skills. It is axiomatic that different does not mean inferior. We have all developed our professions along historical and cultural lines which have worked for us in the past and which continue to work for us today. It must be recognised that we can achieve the same ends (free movement of professionals) by respecting and understanding and not disrupting or replacing existing professional educational processes which are based largely on our own historical cultural values and national requirements. Understanding of and a respect for the cultural norms and values of both the individual professional and the countries in which the professional activities are to be performed will ensure that any barriers to free movement are minimised and that we are all free to develop our profession in ways which best reflects the needs of our members and our clients within a global marketplace. Inevitably, one of the essentials to achieving the free movement of professionals is the recognition and acceptance by our clients of our particular skills, but that is more of a promotional exercise, not one of "internal" restructuring. Surveyors have professional skills which are vital for the success of the global marketplace. We now need to communicate effectively in order to develop our understanding of post-qualificational professional practice and standards on which mutual recognition can be based. This research has contributed to and furthered the debate. ReferencesEuropean Council, 1989. European Council's Directive on a general system

for the recognition of higher-education diplomas awarded on completion of

professional education and training of at least three years' duration.

European Council 89/48/EEC. AcknowledgementsThe author is grateful for the advice of Mrs Carol Clark, the UK Co-ordinator for Directive 89/48/EEC Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications, on this research and to the respondents who provided completed questionnaires on which the results of this research are based. The author is also grateful for the support of research colleagues, Professor Stig Enemark, Professor Hans Mattsson and Dr. Tom Kennie and to Mr. Paddy Prendergast and the CLGE and FIG for financial support in the production of this research. Biographical NotesDr. Frances Plimmer is Reader in Applied Valuation at the University of Glamorgan, Wales, UK and head of the University's Real Estate Appraisal Research Unit. She is a Fellow of The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyor and an inaugural member of the Delphi advisory group to the RICS's Research Foundation. She is the RICS's delegate to FIG's Commission 2 (Professional Education) and the official secretary to FIG's Task Force on Mutual Recognition. She has been researching into the EU's Directive on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications since 1988 and has had several paper published on this subject. She is the editor of Property Management and a Faculty Associate of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Massachusetts, USA, and is part of an international research team investigating issues of equity and fairness in land taxation. She can be contacted at The Centre for Research in the Built Environment, University of Glamorgan, Pontypridd, Rhondda Cynon Taff, Wales, CF37 1DL, UK. Tel: + 44 (0)14 43 48 2125 Fax: + 44 (0) 14 43 48 21 69, email: [email protected] and web site www.glam.ac.uk |

||