FIG PUBLICATION NO. 43Costa Rica Declaration

|

|

|

|

|

This publication as a .pdf-file (38 pages - 583 KB) |

Costa Rica Declaration on Pro-Poor Coastal Zone Management

2. Key Conflicts in the Coastal Zones

3. Understanding the Concept of Resilience

4. Managing Land Tenure and Property Rights in Coastal Areas

5. Managing Access to Land in Coastal Areas

6. Managing Use and Allocation of Land in Coastal Areas

7. Building the Institutional Capacity

8. Building the Professional Capacity

Photographs in this publication © Stig Enemark, FIG, 2008.

The land-sea interface is one of the most complex areas of management being the home to an increasing number of activities, rights and interests. The coastal zone is a gateway to the oceans resources, a livelihood for local communities, a reserve for special flora and fauna, and an attractive area for leisure and tourism. Many nations – and especially in the Central American region – are politically, economically, socially, and environmentally dependent on the costal zone and proper management of this fragile environment to meet requirements for sustainability and social justice.

The coastal areas were therefore chosen as the key theme of the 6th FIG Regional Conference held in San José, Costa Rica, 12–15 November 2007. Special attention was given to a pro-poor approach to integrated coastal zone management, measures for proper land administration, and capacity building in terms of professional and institutional development.

The theme of Integrated Coastal Zone Management has been widely researched and documented in publications throughout the world. This publication looks more specifically at providing a pro-poor approach to managing the interests and rights in the coastal areas, and the role of the land professionals in this regard.

This publication stresses a topic of special importance in Central America but the issue has much wider regional and global implications. FIG as a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) wants to contribute to the global agenda as represented by the United Nations Millennium Development Goals aiming to eradicate poverty in all its forms. A pro-poor approach to managing the many, often conflicting, interests in the coastal zone is therefore of vital importance. The publication should be seen as a tool to support politicians, executive managers, professional organisations and decision makers in their efforts to manage the fragile coastal environment with a special emphasis on social justice and the livelihood of the local communities.

An expert group appointed at the 2007 FIG Regional Conference in Costa Rica has prepared the Costa Rica Declaration. Rob Mahoney of FIG Commission 3 chaired this group. The members of the group were:

The document is based on the papers presented at the 6th FIG Regional Conference, 12–15 November 2007, San José, Costa Rica, especially the keynote presentations given by Ing. Juan Manuel Castro Alfaro, President of CFIA/CIT, Prof Stig Enemark, FIG President and Mr Fernando Zumbado, the Costa Rican Minister of Housing. Other keynote presentations at the conference have also been of great benefit to this publication. These include papers from Dr. Diane Dumashie, Mr. Alexander González Salas, Dr. Michael Sutherland, Ass. Prof. Grenville Barnes, Mr. Stephen T. Mague and Mr. Robert W. Foster.

Conference proceedings are available on-line at: http://www.fig.net/pub/costarica/

This event chose to focus on key topics for the region – capacity building, land administration and environmental issues – especially the use and future of coastal regions. Based on the out-come of the conference the FIG Costa Rica Declaration outlines where Land Professionals can and should play a key role in managing and influencing the complex issues of Pro-Poor Coastal Zone Management. The Costa Rica Declaration was launched at the FIG Working Week in Stockholm, Sweden, 14–19 June, 2008.

On behalf of the FIG, I would like to thank the members of the expert group and all the specialists who contributed to this publication for their constructive and helpful work.

| Stig Enemark FIG President June 2008 |

The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) acknowledges the pressure being placed upon Coastal Zones and the urgent need for resilience and the support of pro-poor policy and programmes in addressing the issues associated in the development of these vulnerable and fragile areas of the world.

The Declaration recommends development in a number of areas including:

FIG supports the right of poor coastal communities to thrive, and retain ongoing access to coastal resources. Multiple use management tools should be developed to achieve social justice in a resilient balance between economic development, environmental protection, and the livelihood of the local communities.

FIG believes that the Land Professional has a key and essential role to play in supporting the setting of strategies and policies; and facilitating the interactions of all professionals, politicians and local communities, thus creating a balance to improve coastal zone management.

The 6th FIG Regional Conference 12–15 November 2007, held in San José, Costa Rica focused on “Coastal Areas and Land Administration – Building the Capacity”. This theme was chosen to address some of the key professional issues in Latin America and especially in Central America and the host country of Costa Rica. The conference recognized that the vulnerability of these regions required urgent action especially in terms of reinforcing a pro-poor approach to coastal zone management.

This document sets out a number of issues: Understanding the Concept of Resilience; Managing Land Tenure Rights; Managing Access to Coastal Areas; Managing Use and Allocation of Land; Building Institutional Capacity; and Professional Capacity as they impact Coastal Zones, and identifies ways forward that, given appropriate support and resources, will improve the cur-rent situation.

A high percentage of the human population lives in coastal zones. Many of these people utilizing the coastal areas are economically poor and need to have access to the costal and marine resources to sustain their livelihood. As a result these areas are extremely important for the management of rights and access to resources, as well as spatial planning and decision-making, particularly for the poor. Land Professionals1) (this includes hydrographers) have a role to play in all these areas of coastal zone management, contributing to equity in resource allocation and social management. In today’s rapidly changing globalised world ethical considerations and governance issues are also relevant to the long term protection of coastal areas and communities.

1) See Glossary of Terms for definition of the Land Professional.

Approximately 70% of the Earth is covered by water of which 97% is saltwater, predominantly seas and oceans. The Earth’s total coastline measures approximately 860,000 Km. However, agreement about what constitutes the extent of a coastal zone either landward or seaward varies among jurisdictions.

The coastal zone itself is an area considered in some European countries to extend seawards to territorial limits, while others regard the edge of the continental shelf at around the 200 m depth contour as the limit.

Broadly speaking a coastal zone is understood to be a defined spatial extent encompassing land (including submerged land), sea, and the land-sea interface, where each entity within the defined spatial extent exerts strong influence upon the others in terms of ecology and uses.

Over 50% of the earth’s population live within 100km of coasts, and this population is expected to increase by 35% by the year 2025. Approximately 634 million people live in coastal zones (defined as areas that are less than 10 metres above sea level). These huge numbers of people are at risk from rising sea levels and extreme weather attributed to climate change. The population density in coastal zones will continue to increase at a greater rate than that of inland areas. The extent of the need for holistic management of the diverse issues associated with coastal zone management is further illustrated by the following facts:

16 nations with the greatest proportion of their populations in threatened coastal zones are small island nations.

Urban development in coastal zones is increasing the number of people at great risk, both by exposing them to seaward hazards and by degrading ecosystems that protect coast-lines, such as flood plains and mangrove swamps.

There are great risks to countries where a large, mostly poor population, inhabits extensive low-lying coastal areas.

Some archipelagic nations that are most vulnerable to climate change effects are also least able to afford the steps necessary to mitigate those effects.

The ability of communities to resist the effects of climate change or to adapt to its’ effects, depends on those communities’ vulnerability to change, their resilience, and capacity to adapt. Threats can be both environmental and socio-economic.

Coastal Zone Management is a complex process and the Land Professional is well placed to assist many of the critical decision support activities, and to facilitate interaction between a diversity of professional, political, environmental and community organisations.

FIG believes that the Land Professional has a key role to play in supporting the setting of strategies and policies; and facilitating the interactions of professionals, politicians and local communities to improve management of vulnerable Coastal zones.

The coastal zones are uniquely sensitive and vulnerable areas. There are a number of key conflict areas some of which are shown below. Ensuring a balance between the natural environment and the human interventions is a great challenge because of the inherent ‘vulnerabilities’ associated with coastal areas.

Coasts are often areas of outstanding natural beauty where development would bring the area into conflict. Conservation orders can protect the pristine coastal areas and preserve vulnerable flora and fauna. More generally, coastal protection lines can be applied to enable targeted control of the potential conflict between economic development and the protection of natural environment.

Increasing human intervention in these areas is challenging natural and diverse habitats, but also the communities that have been residing there for some time. Coastal zones are dynamic environments which are naturally susceptible to changes such as:

tidal erosion and the deposit of material

changes in water quality the results of which can be positive or negative

increase in commercial activity

increase in recreational activity

global warming – resulting in algal blooms; rise in sea level; increased storm frequency and severity; erosion and increased sedimentation.

Figure 2.1: Coastal area of outstanding natural beauty. Otago Peninsula,

New Zealand.

The negative consequences of some of these changes to ocean and coastal characteristics, as well as to coastal communities, include:

coastal erosion and flooding and damage to coastal habitats

increased water pollution, that adversely affect freshwater resources

devastation to marine life

loss of unprotected dry land and wetlands

loss of exclusive economic rights over extensive areas

destruction of existing economic infrastructures and commercial activities.

Stakeholders from diverse economic and social groups share and compete for space in coastal zones worldwide. Affluent commercial and economically wealthy stakeholders have the potential to severely limit access to resources for poor communities.

Coastal zones have many uses and serve many functions. These areas provide natural, social and economic facilities that contribute to increased quality of life, and the oceans are instrumental in determining climate. A great variety of social and economic activity takes place in coastal zones including:

tourism

commercial and recreational fishing

oil and gas development

habitats for endangered species, species breeding and resting areas

groundwater recharge

water treatment; and

flood attenuation.

Coastal zones are also sources of community wealth, providing:

sources of food from animals, plants and fish

means of transportation

means of communication (e.g. cables)

areas for implanting fixed navigational installations (e.g. lighthouses and piers)

areas for the dumping of waste materials; and

areas for scientific research on Earth’s basic physical and biological processes.

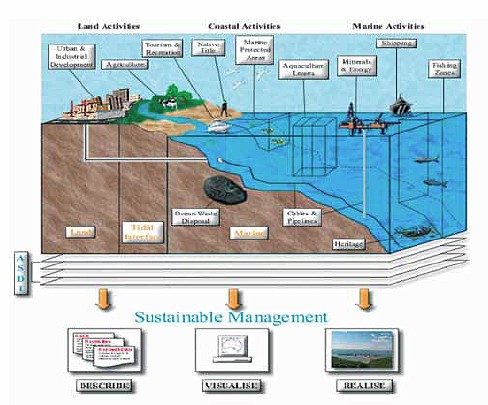

The interaction of multiple uses in the coastal zone is illustrated in Figure 2.2 showing the range of rights and restrictions in a seamless information system for the land and sea interface.

Figure 2.2: Illustration of multiple interests in the coastal zone. Binns

et al. 2003.

In this context good governance is characterised by an acceptable balance of stakeholder access to resources, ensuring that competing needs and agendas can be met with as little conflict as possible. Managing this, is difficult in an area that is dynamic, constrained by space, and is particularly at risk to global changes whether these are driven by climate or economics.

Increasing urbanisation in the coastal zones can bring into conflict the balance between economic development, the livelihood of local communities, and protection of the natural environment.

Such conflicts may occur in a more extreme form where the natural livelihood of the indigenous population and their access to the coastal resources is taken over by economic interests. These include tourism and leisure development that will not necessarily benefit the low-income people and the local community. In this extreme form indigenous people are displaced from their original spaces and places and may need to relocate in informal settlements with limited basic ser-vices, unacceptable environmental conditions and few or no work opportunities.

Many coastal communities live in, or are at risk from socio-economic poverty. This can have a negative environmental effect upon coastal zones with poverty driving resource overuse and ultimately, environmental degradation. Coastal management policies should ensure equity in terms of access to coastal spaces and other coastal resources and be underpinned by pro-poor policy change and national poverty reduction strategies.

More generally, the disassociation of social systems from ecological systems can also cause conflict. This has made it more difficult to understand complex human-environmental interactions that occur when external pressures such as increased tourism alter the existing balance.

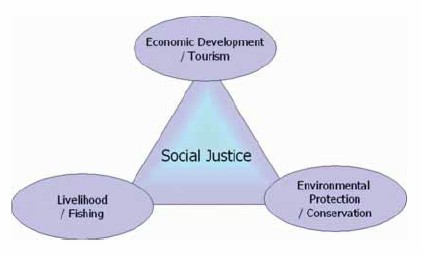

FIG believes that a multiple use management in coastal areas should be based on a principle of “social justice” where a balance is found between the various interests of economic development, community livelihoods, and environmental protection. Such a pro-poor approach to coastal zone management is argued throughout this document.

Local community harbour area, Pacific coast, Costa Rica.

The concept of resilience can provide a new and useful perspective on sustainable development. At its core is the idea that development processes should not and must not threaten the ability of future generations to share the earth’s resources, as previous generations have been able to. State and regional governments, multi-national corporations, local industry and the in-habitants of the Coastal Zones are under increasing pressure to balance economic growth with social responsibility, including respect for human rights and traditional cultures. Furthermore, all organisations involved in Coastal Zones and occupants of these areas are being asked to take greater responsibility for their ecological “footprint”.

Resilience can be regarded as an operational tool for recognising, improving and measuring corporate sustainability. Whilst the definition of ‘Resilience’ may appear to be very close to the definition of ‘Sustainability’, they are not synonyms:

Resilience is basically about recovery and adaptation to change while sustainability is mainly about survival and continuing existence.

Resilience is stressing the importance of assuming change and explaining stability; in-stead of assuming stability and explaining change.

There is an inextricable relationship between social wellbeing, economic development and environmental sustainability as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Relationship diagram between social wellbeing,

economic development and environmental sustainability.

Sustainability is often misinterpreted as a goal to which we should all aspire. However sustain-ability is not a reachable state; it is one fundamental characteristic in a dynamic, evolving sys-tem. Long-term sustainability will occur as a result of continuous adaptation (resilience) to changing conditions. It cannot be assumed that nature will be infinitely resilient, and neither should it be assumed that it is possible to predict the cycles of change that may occur in the future. A sustainable culture should be based on a dynamic world-view in which growth and trans-formation are inevitable. In such a world, innovation and adaptation will enable human societies – and enterprises – to flourish in harmony with the environment.

A resilience approach accepts this interpretation of sustainability. There is not one single stable state in a social-ecological system, instead the system will be exposed to different ‘shocks’ that challenge its fundamental identity and make it dynamic. A resilient system is able to absorb shocks and adapt (and therefore remain sustainable) without changing its fundamental structure and function. The concept of resilience needs to be at the centre of strategic thinking about the actions that shape the future management of the Coastal Zones. Resilience needs to be applied to people, agencies and organisations as well as the environment. The lack of resilience in political and governance processes and procedures is a major impediment to advancing sustainability.

Land administration systems are the subject of constant change and therefore require an in-built resilience to ensure they do not become out-dated. Resilience of land administration systems can be understood by looking at natural disasters such as hurricanes and tsunamis. The resilience of a land administration system and how it is governed plays a key role in recovery and reconstruction efforts following natural disasters. The resilience framework is highly appropriate for trying to not only understand the role that land administration systems have played in past disasters, but more importantly how these systems can be strengthen to better support recovery and reconstruction in future disasters.

There are many instances where projects come to an end without having made provision for immediate succession planning. If development is the managed process of change designed to improve the conditions of members of a society, then sustainable development should balance the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments and the advancement of technology in a manner that affords the same opportunity to future generations.

Change is inevitable, to what extent can only be guessed, but today’s generation should not be frightened of it, nor shrink from addressing it. There is a need to change both the mindset and the toolkit for managing change in coastal zones. Most importantly, every tool at our disposal should be used for sound, effective, rational and unencumbered coastal management, rooted in equity and a social justice framework.

Pressure to develop the Coastal Zones will continue, the challenge is to introduce mechanisms which will provide for equitable treatment of all those who live, work or invest in them. One of the many challenges of introducing resilience analyses is to define what constitutes the ‘fundamental structure and function’ of a system.

The concept of protecting the rights of future generations seems remote in the face of the many contemporary and often seemingly conflicting business pressures. Typically many governments and businesses fear that the creation of strategic policy on sustainability will simply involve expenditure without any tangible result. There is a need to reinforce the message that economic, environmental and social progress can be mutually supportive, and the business case for sustainability rests on enhancing intangible value drivers rather than directly generating financial profit.

There are real barriers to be overcome to ensure that the concepts of resilience and sustainability are understood and translated into strategy and policy; and then delivered by those working on the ground in everyday practical decision-making situations. Using a new language that is relevant to business interests, rather than relying on stakeholder pressures and the moral force of arguments may overcome many of the barriers to the drive for sustainability. This requires viewing the enterprise as closely allied to a variety of social, environmental, and economic systems. This in turn necessitates that land administration systems focus on parcels of land that are undergoing the most change or which may be susceptible to change.

There is a need to bring together groups of government officials and professional bodies and for them to take a holistic view of the strategies and policies which impact on coastal zone management. In addition they need to agree on the tools, mechanisms and information systems needed to inform decision-making in all areas, from land and property tenure to marine ecology, and overall spatial planning and development.

There is a need to ensure that capacity building is undertaken at all levels in countries that are managing the Coastal Zones; within Universities and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) or Life Long Learning (LLL), and in a number of associated professions – Architects, Engineers, Land Professionals (this includes, Land and Hydrographic Surveyors, Cadastral Experts, and Environmental Surveyors), Lawyers and central and local government (municipality) officers.

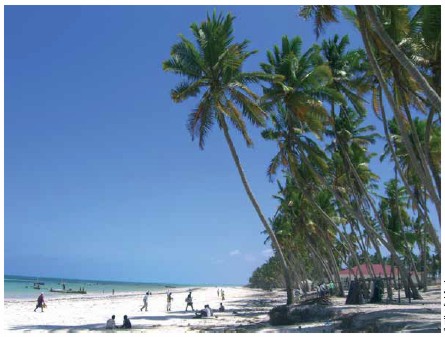

Zanzibar, East Coast.

The rights of property and the land tenure in the coastal zone can often be subject to different legal jurisdictions. The general objective is to regulate and to guarantee access to different interest groups. However, the reality is that this results in considerable conflict, disputes, claims and counter claims associated with land tenure.

Drawing from experience in Costa Rica, this section deals with three aspects related to the rights of property and the land tenure in the coastal zone:

Different types from property rights and land tenure;

Conflicts through legal contradictions in land tenure; and

Activities of land professional attempting to bring about harmonious interaction between the administration of and sustainable human development in coastal zones.

The sea has always been of strategic importance in the organisation of societies. Access to the sea and the consequent control of the coastal zone were essential for the consolidation of many countries.

In the past century, many states, using different legal mechanisms, sought to consolidate the governmental function of the coastal zone. This was designed to ensure that access to all citizens was guaranteed and different uses permitted. In many cases consolidation of land and property rights created tension between existing owners and the demarcation of other interests, for example parks and national reserves.

In many countries, mainly of the third world, the coastal zone is subject to various interests. Each of these base their understanding of their rights on different laws or their own particular interpretations of the law. The resolution of these issues is far from transparent, creating a situation where the insecurity and precarious day to day living of many vulnerable people makes development difficult.

The ideal situation, where the government provides for universal access to the coastal zone, contrasts with the reality where different groups claim the right to occupation. The reasons can often be traced back to different legal frameworks and historical traditions between three groups: settlers, concessionaires and the owners.

The coastal zone has been occupied or possessed for centuries. Once the state introduced regulations concerning access and use, the rights of those occupants or settlers was recognized. Recognition of settlers’ occupation can apply to individual or communal property. This ensures that traditional or indigenous groups are guaranteed land or territories by the states to enable them to preserve their customs and means of subsistence.

The concessionaires are those who have agreed to a legal framework and obtained a use right to public property that is regulated. These use rights permit some activities by the concessionaires whilst restricting the use by others.

It is under this approach that the tourist industry, from large complexes to small family units, has been developed. This also stabilises other activities for example traditional or artisan fishing.

Despite the generalised concept and public character of the coastal zone, in some cases the State recognises individual property rights which encourage the owners to come forward.

The recognition of legally secure private property in lands of the coastal zone, is often based on older laws, approved prior to the official regulations of the coastal zone. For example, in Costa Rica, titles granted by Spanish Crown at the time of colonisation are still recognised. These rights of property find greater endorsement in the countries that have consolidated and respected systems of land estate recording.

The regulation of the land tenure and property rights in the coastal zone presents significant weaknesses that require attention. These weaknesses originate from different legal frameworks that are generally contradictory and can be out of step with the reality of the occupation in the coastal zone. The management of the coastal zone can be shared by several tiers of government causing confusion between the institutions and sectors of society.

Generally property or land tenure disputes occurring in the coastal zone arise because there is no clear identification and boundary of rights of property or possession. In most cases the Institutions of the State do not have appropriate information systems and those that do exist show little clarity in showing the boundary of the rights of different groups.

A consequence of this lack of clarity on the rights of proprietors, concessionaires and settlers, is the emergence of a new player, “the occupant”. The confusion in the legal rights associated with the coastal zone allows “anyone” to allege rights, and to establish occupation with the purpose of making use of the land for a variety of interests.

There is an urgent need for the state to create territorial information systems, which allow for the control of the coastal zone within an agreed legal framework thus enabling holistic decision-making.

Today the state is not the absolute owner of the coastal zone and there are both formal and informal levels of occupation and use of rights. In general formal possession is based on legal mechanisms that the state has established to allow the possession by individuals; and on the other hand informal occupants have no legality and are unable to exert pressure to protect their rights within the coastal zone.

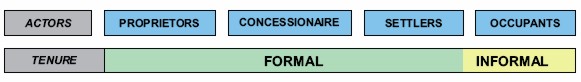

There is a need to make a clear distinction between informal and formal rights and occupation thereby providing formal rights to proprietors, concessionaires and settlers, endorsed by the legal frame that guarantees their right. Figure 4.1 shows this simple separation.

Figure 4.1: Ideal separation between formal and informal possession.

There are also problems with the informal rights. In the Third World Countries the systems of right of property and land tenure are not always transparent and some people allege rights that have been granted by one institution of state that are then not recognised by another. This mainly occurs where there are traditional settlers or indigenous towns in the coastal zone.

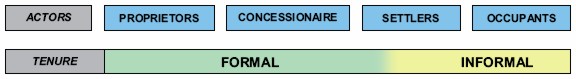

The reality is that, with the enormous interest in the coastal zone, the diversity of administrative controls used by the state means that the line between formal and information rights becomes diffused. The result is shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2: Realistic separation between formal and informal possession.

The separation between formal and informal varies in different countries, according to the legal framework that regulates the property rights and land tenure in the coastal zone. Even within the same country, regional differences in the level of formality are often found. The difficulties in determining legal property boundaries are exacerbated by a lack of clarity about the exact physical extent of what is included or excluded from the coastal zone.

In order to reach a harmonious, sustainable and resilient development of the coastal zone there is a requirement to approach the issues holistically. Three of the key factors that will maximise the effective management of these areas are:

The creation of a uniform Cadastre following the key

guidelines in FIG Cadastre 2014 declaration 1 – “the cadastre will indicate

the complete legal situation of territory, including public right and

restrictions”.

The creation of, and implementation of, a Land Information System to bring together all information sets that impact the costal zones. These critical data sets would enable co-ordination of strategy and planning, and these would include:

land tenure (Cadastre) Marine Cadastre, especially in river deltas

land and property rights (continuum of rights in a broad approach, including public land)

customary and indigenous rights

marine management

access rights

transportation

bio diversity.

The use of Land Professionals in facilitating and bringing together all professional groups and tiers of government.

There is also the need for the institutional reform of those organisations responsible for the coastal zone, ensuring a prioritising of policy issues and overall coordination.

The diverse skills of Land Professionals enable them to play an active roll in the promotion and development of Land Information Systems. In addition their multi-disciplinary facilitation skills provide the opportunity for them to bring together those responsible for the administration of the coastal zone and the local and indigenous people who often feel disenfranchised.

Jakarta, Indonesia

The physical resources in the coastal zone have a dramatic influence on people and the distribution of population including the tourist. In developing countries existing communities are be-coming increasingly marginalised, and in environmentally attractive areas access is one of the most important challenges of coastal and marine management.

Finding a sustainable answer to the issues of maintaining access to these areas requires coordination of long term planning and management of recreation and tourism. The resources that have provided the foundation for economic development in the coastal region are now in jeopardy. Without appropriate intervention the outlook for these areas is one of declining human welfare, declining resources and increasing use conflict.

The quality of life in coastal communities is inextricably linked to the quality of the coastal and marine resources. Levels of poverty are increasing in these areas, evidenced by decreasing fish catch, destructive fishing practices, and an increasing volume of untreated sewage and nutrient run off released into near shore areas.

Usually human activities relating to land use are regulated on the basis of subdividing an area or a resource, and then allocating subunits for different purposes. This is not an option available for coastal lands and their resources, due to the highly prized, yet fragile nature of the resource.

It is unacceptable to alienate existing and often increasingly poor communities from coastal re-sources. Social justice is politically necessary and to achieve this requires a joined up community approach that combines policy with action on the ground to conserve coastal resources for access by all community groups. In order to deliver a jointly agreed and sustainable future for all society, Coastal Zone Management frameworks need to combine a strategic focus found in land administration. The resulting strategy should provide a management framework for a holistic programme, and a vision of integrated management for the coastal zone.

Land, sea and people need to be better managed in a spatial sense. Coastal Zone Management is inevitably a complex process, but this paradigm requires change, and needs to recognise the multiplicity of issues including resource use, capacity, administration, registration of rights and planning.

The management task is to balance economic development, social needs and environmental protection. Within land administration this is a function of spatial planning and development.

Distribution of economic resources, and consequently the ability to manage resilience, is very different in the north to countries in the south. In the north, an industrial and now post-industrial society, such impoverishment of our local resources is counterbalanced by massive inflows of resources of every kind from other regions of the world. However, for many societies experiencing the same coastal transformation process today, such flows of goods, and the subsidies that have underwritten the cost of development, are nowhere on the horizon. Specifically public and private use may be in conflict in ecological areas that appeal to tourists seeking a ‘pristine’ beachside environment for the purposes of holiday, leisure and recreation in tropical destinations.

As these communities are growing, there is increasing pressure on the capacity of the environments to sustain even the increasing village communities. Tourism development and disaster protection are two key conflicts in Central America and small island states which relate to both physical and economic vulnerability, and completely undermine local communities.

Coastal and island states are experiencing increasing pressure on land and their resources but the economic benefits, particularly tourism and related development are not necessarily benefiting low-income people. In some instances these people are displaced from their original spaces and have no option but to relocate and settle in informal settlements with limited basic services, unacceptable environmental conditions and few or no work opportunities. A typology is emerging that tourism is reducing access to resources for the local community and is further impacting on fragile resources.

Recreation is one of the largest and fastest growing uses of the coastal zone. Through tourism some of the leisure and recreation needs of affluent and largely urban communities may be fulfilled at distant locations. Coastal tourism development is a legitimate goal, with many private sector schemes proving to be reasonable from a conservation or preservationist perspective. Tourism can provide the motivation for conservation and community level decision-makers to appreciate the values of high environmental quality and attractive local community goods and services. It can generate long-term economy and social benefits locally, nationally, and for the global community.

However, a proliferation of private sector developments has proven to be irresponsible from a conservation, preservation or community perspective.

Tourism has resulted in alien values being imposed upon long established local communities who rely on marine resources for their livelihoods.

Historic settlements and new urban development are often located in some of the most beautiful natural environments in the world. These urban developments and settlements were largely un-planned, encroaching on the beaches, water bodies, wetlands, and wildlife sanctuaries.

Increasingly, coastal destruction and extreme weather events have introduced a new and disruptive dimension to coastal zone management: a risk to the coastal balance of land use, to communities living on the coast, fisheries, the tourist industry, infrastructure, and buildings. The risk falls disproportionally onto the poor. Indigenous coastal communities, often as a result of tourism development, are built on marginal land such as flood plains and coastal swamps, making poor people particularly vulnerable to events such as flood, storm surges and fire.

The effect of climate change on human settlements could have been minimised by urban planning. Early warning systems are being set up, but alongside this, more attention needs to be paid to improving the planning of human settlements.

Assessing risk requires both building community resilience in a rapidly urbanising world, and exploring the extent to which property rights (public, common and private) and property economic tools could combine and meet the objectives of sustainable development through public private partnerships.

In the aftermath of natural disasters, the urgency of livelihood and habitat restoration adds a new dimension to coastal zone management issues including alleviating poverty, reducing environmental degradation and enforcing set back lines. Planners should identify immediate tasks in which the local community members can become involved; both to earn a wage and ensure coastal habitats are restored as quickly as possible.

Social justice must be the outcome of the interaction between communities living in coastal zones and their need for access to resources in competition with both the extractive and tourist industries.

This raises a number of issues that need to be addressed including:

rights of access for coastal communities to marine resources

viability and social status of communities in the coastal zone

provision of power, capability and rights of communities to engage in decision making in cases of conflict

reassessment of the role of Central or State government and local jurisdictions in multiple use management, for example when overseas tourism developments alienate local communities

the redefinition of the Coastal Zone Management paradigm in respect of land administration.

The way forward is to develop an appropriate a balance between resource development for communities and resource protection. Cases of development conflict are often about public and private sector relationships and the nature of associated property interest.

Development has to be a process that takes account of the multiplicity of issues in coastal areas while being embedded into a social justice paradigm.

This application of land management links land to social justice, and accommodates the original coastal community and their need for resource access in the face of the economically powerful tourism and leisure community.

There is considerable concern over the conflict of space between the local community and the increasing pressure of tourism development in the Coastal Zone. There is a need to utilise, and where necessary develop practical management tools that recognise social justice and the living conditions of the poor.

Achieving the balance between competing uses involves understanding the multiple uses that occur in a relatively confined space and requires a spatial approach for effective management. Concerted action is needed both to correct past mistakes and to ensure sustainability and resilience into the future. The continued decline of these same resources is due to poorly coordinated enforcement and unplanned resource exploitation.

Spatial concepts can be used to highlight the inter-relationships, nature and proximity of people and uses within the linear constraints of the coastal zone. The nature of conflicts will vary; some uses are in competition for the same resources, others may conflict in time and space only. To make multiple use management operate successfully, there must be greater knowledge of the relationship between economic and social use. In addition investment must be made in the appropriate technologies to use the data efficiently.

Direct users of the marine environment such as fisheries and some forms of recreational and tourism benefit from, and are affected by, the maintenance of environmental quality. Unless short term economic outlook for their industry is poor, they are likely to be concerned about any reduction in quality. They are likely to accept, at least in the long term, management measures that maintain the productive natural qualities of a marine environment.

Managing the inter-relationship of multiple community objectives takes into account different community perspectives of coastal resources linked to the conservation of that resource. This perspective depends on subjective judgements concerning the amenity value of the environment, and covers a broad range of intentional human interactions with biological resources and natural areas. Articulating this value reveals fundamental differences of opinion around the relationship between humans and the natural environment. These differences often reflect the degree and nature of economic dependence upon the resources of natural areas.

Multiple use management approaches may be summarised in a diagram Figure 6.1 which illustrates the area in which a decision or group of decisions will conform technically with a requirement to address the concerns of three interest groups: conservation, tourism and livelihood/ fishing. The mid-point of the ‘Equality Triangle’ represents the ‘perfect’ solution.

Figure 6.1: The ‘Equity Triangle’, for Access to, and sustainable use of,

coastal resources.

Social justice is a product of the way society is organised and is affected by competition for ac-cess to coastal resources for livelihood on the one hand, and for leisure tourism on the other, as outlined in the equity triangle.

The three corners of the equity triangle work as competing forces. In general, tourism looks to amenity value, while local communities will value their livelihoods.

Economically there is a stark contrast in the relative affluence and life styles of tourists and members of the local community. This has the potential to provoke discontent and unrest. The tourism industry can mitigate against this by ensuring that local communities reap some of the benefits of tourism. Conflict can also be reduced by maintaining access to the common resource of the sea for both communities living in coastal zones and tourists.

This demands a holistic approach such as land administration and spatial planning tools to support Coastal Zone Management.

Planning is only the first step in management – it is not an end in itself. Integrated Coastal Zone Management from a land use perspective requires both understanding of the planning and land administration process. Initially there is a need to acknowledge that a problem exists, and that tools are required to control and administer resource conflict and use within a functional area of highly interdependent uses.

Spatial tools must be pro-poor and practice-based. Many practitioners accept that in the real world some compromises are always going to be required. National and local governments need to be seen to protect all their citizens and ensure that economic power does not override indigenous rights and needs.

In Land Use and Development planning there are a range of tools that can be used to support decision making, these include:

policy approaches to address multiple uses over the coastal zone or space, including existing poor communities that are increasingly becoming marginalised and disaffected from the resources available in the coastal zone

proposed strategic management framework(s) that will bridge economic development, community and environmental protection issues

stewardship of land and marine resource

technologies such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and satellite imagery

shoreline management plans based on catchments that considers natural physical processes

planning policy tools, such as development set back lines

achieving unity of vision through master planning – a spatial planning process that sets out a plan for the future development of an area and community education.

The challenge is that sustainability and resilience requires community engagement, for rich and poor alike. This will require tools that foster collaboration, access capacity building, and education.

A change in culture is required to encourage those who are responsible for the Coastal Zones to understand the larger complex issues and adopt flexible and adaptable processes and policies. There is a need to develop systems in preparation for rare but devastating events; to use a combination of instruments; get all stakeholders involved; and to develop local solutions to local problems. Progress can only be made if the ability exists to deliver Coastal Zone Management at various scales from regional, national to local levels and be adaptable to a range of circum-stances.

Effective planning requires a local, bottom up approach building from two bases: the ecological basis of the best available understanding of the natural system and processes of the area – this means engaging with local knowledge; and the socio-economic basis of the needs and expectations of those who use or value the resources of the area. This often requires research and community education in order to demonstrate cause and effect of human impacts and to establish that management has the potential to halt or reverse decline in amenity.

Good governance is required to maintain a strategic, global view interacting with the international community, on forces that pull, such as the environment, but also forces that push – in the case of tourism markets. At the local level cash income generated by tourism, should be diverted to support the involvement of communities in planning for post disaster rehabilitation, disaster risk reduction and the design of more disaster resistant settlements.

Land Professionals are ideally placed to work with all parties to facilitate solutions to the complex planning issues in the Coastal Zones. The outcomes of this facilitation should aim to be:

Based on local economies with much more emphasis on social responsibility. Local solutions to planning and environmental management would be encouraged. There would be local community partnerships, potentially with international corporations, with some profits from tourism channelled back into the local community. A substantial, high degree, of local capacity leadership building will be required to foster equitable community managed access to resources.

Supporting global sustainable development with a high emphasis on international action and international obligations. This requires a strong commitment to regulation and more proactive management of resources and landscapes. Coastal and Marine regional proto-cols signed up by States would be emphasised. Although good for marine and coastal biodiversity, it requires a parallel community policy approach to land and resource management.

A strategic framework for effective policy and programme development is required to achieve a fully integrated Coastal Area Management process and investment in spatial technologies and data sets.

Awareness of the resources and their protection is increasing, and leading to an increase in the number of conservation activities. Government agencies, NGO’s, community based organisations and indigenous communities need to play a pivotal role in managing coastal assets. Any coastal initiative should be concerned with including these groups to the extent that collaborative partnerships are developed. Sustainable coastal development can only be achieved when the governance process responds to, and is accountable to, the people who live with the results.

Ultimately, the impact of the tourism population pressure on people’s lives can be greatly reduced by effective forward planning and governance, but this will require adherence to the principle of social justice.

Zanzibar, East coast.

In many countries, including Costa Rica, there is no single agency responsible for the management of the coastal zone, and in some cases no specific level of government with responsibility for all aspects of strategy and management. This makes it more difficult for governments and institutions to respond to the complexity of issues involved.

The result can be indecision, and contradictory legislation and decision making, leaving those responsible for the management of the areas confused and without clear and effectives means of redress, or ability to challenge what they see as an impenetrable institutional body. In tropical zones many new houses are being constructed as holiday homes for foreign nationals who re-side in them for only part of the year. This places pressure across all aspects of the local economy. Good planning and legal frameworks are required to provide a balance between inward investors, the indigenous population and environmental protection.

Good governance is based on recognition of the interests of all stakeholders and inclusion of their interests where possible. Interests can be expressed in a variety of ways, for example: sovereignty, jurisdiction, administration, ownership (title), lease, license, permit, quota, customary rights, indigenous rights, collective rights, community rights, littoral rights, public rights, rights of use, and public good. Coastal states are challenged with managing the multi-dimensional tapestry of these interests (and perhaps others) on the coast and offshore. Over the next few decades those responsible for marine policy and administration will be challenged with trying to understand this tapestry and communicating it to the various decision makers and stakeholders. However, addressing the complexities associated with these interests solely from a boundary delimitation perspective does not necessarily improve the governance of marine spaces.

The many people who have settled in coastal zones to take advantage of the range of opportunities for food production, transportation, recreation and other human activities deserve the benefits of good governance. All too often, coastal zone management has simply become a process of managing or at best mediating conflicts between the multitude of users of what can be scarce resources, and addressing current problems that result from stakeholders pursuing their own sectoral interests. The ‘status quo’ may be maintained in order to avoid conflict, al-though there is a potentially large risk that this apparent stability is not sustainable and could collapse if society cannot make the social, economic and political changes necessary for survival.

In spite of many local and national efforts, traditional approaches to the management and use of coastal resources have often proved to be insufficient to achieve sustainable development. The professional institutions have been unable or unwilling to provide the conditions that could facilitate development, stimulate progress and encourage a change in institutional behaviour in order to achieve shared goals.

There is a real need to determine mechanisms which will ensure coordination between national, regional, local governments (municipalities) and professional institutions.

Traditional government structures are often committee based and slow in making certain strategic decisions. A holistic approach to decision making is required to ensure that all parties are involved and represented and that an effective means is established to ensure that decisive decisions are made.

There is a growing awareness of the issues surrounding the Coastal Zones and the conflicting pressures on these fragile resources. Nations are generally now more conscious of the fact that the actions of individuals can have global consequences.

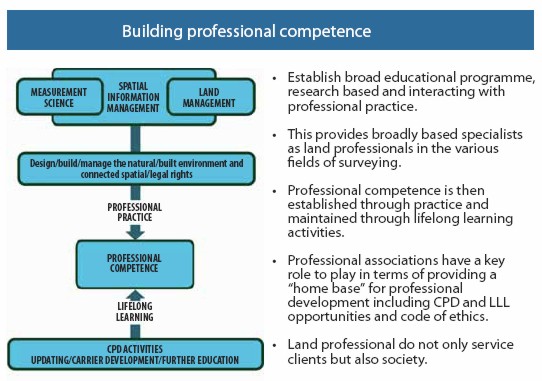

The development of Land Professionals is key to the vision of sustainable and resilient development of the Coastal Zones – a major challenge but one that is essential if change is to be achieved. This requires the acceptance by other associated professional institutions of the skills and abilities of the Land Professional. The Land Professional is required to possess a large knowledge derived from high level education and practical training. These Professional skills are important to the well being of society. Professionals are expected to utilise their independent judgment in carrying out their professional responsibilities and they are regulated by ethical standards. Land Professionals are expected to place the interests of society above these of the individual member. This is important in developing the trust of all those involved in the Coastal zones.

The development and maintenance of the Professional capacity is illustrated in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1: Land Professions Capacity Model. S. Enemark.

The Land Professional, together with those of other related Professional disciplines, needs to be conscious of the fragility of the coastal zone in order to influence decisions. There are two fundamental aspects that guide the development of the Land Professional:

There is a requirement for all Land Professionals to ensure their skills are permanently up-to-date and appropriate for the work they undertake. In the coastal zones, in addition to the direct skills that are required for their specialism, all professionals should ensure that they develop and maintain skills incorporating the ethical issues with which they need to engage, including the needs and rights of indigenous and minority groups.

The coastal zones require Land Professionals to strictly adhere to the principles of sustainability and resilience in order to promote balanced development and facilitate the coexistence of different users and the environment.

In developing countries in particular, major corporations and the Land Professionals can act together to promote a consciousness in all professional groups that recognises the pressures on the real estate market, and the need to create a vision of social development that incorporates a balanced approach to the development of the environment.

One consequence of globalisation and the opening up of markets to foreign participation is the need for professional and ethical standards that apply to all. This is to ensure fair competition, to build and retain the confidence of clients, to protect the environment, and to respect the interests of third parties.

One mark of a Professional Institution or Organisation is that its members are subject to a code of ethics. These codes of practice are generic and it is necessary to be able to put theory into practice. Ethical standards should be monitored and enforced to ensure that they are being appropriately applied in practice.

Courses and case studies need to be developed that show best practice in the application of codes of ethics in practical situations. This requires a commitment to bring together the under-standing of ethics in a number of dimensions: social, technological, administrative and environ-mental. This practical understanding can then ensure that appropriate ethical standards are applied to sustainable and balanced development of the coastal zone.

The practical complexity of applying ethics must be at the core of Land Professionals’ daily activity. In sensitive and fragile areas such as the Coastal Zone the balance between one course of action or decision and another requires careful assessment of often conflicting priorities.

The Land Professionals skills should not be confused with those of the technician – to set out boundaries or parcels. The Land Professional’s ethics perspective covers a wide and eclectic set of disciplines which can support the bringing together of different professional groups, and facilitate or mediate outcomes beneficial to all parties. This entails commitment beyond the con-fines of a specific project.

Given the financial and organisational constraints facing institutions and groups involved in the coastal zone, innovative ways to maximise learning and increase knowledge must be introduced. There is a need to ensure that both professional institutions and corporations promote understanding of the issues that surround the Coastal Zones. This should promote a detailed understanding of the complex balance of competing interests that include social dimensions.

All professional institutions, state administrations and corporations should ensure that their staff are encouraged to maintain and update their skills and understanding of the issues associated with the Coastal Zones.

A commitment to Continuing Professional Development (CPD) and Life Long Learning (LLL) is essential to the work of all Professionals throughout their career in order to extend their knowledge, skills and experience. There must be a conscious effort to bring about an environment where this practice becomes accepted behaviour.

Land Professionals and all professional groups whose work impacts the activities within the Coastal Zones should discharge their professional duties in accordance with a model code of professional conduct and adhere to ethical principles. Courses must be provided to ensure that ethical codes are introduced (where they are currently unavailable), and practical case studies are used to enable participants to become proficient in putting theory into practice.

Dar es Salaam harbour, Tanzania

A surveyor is a professional person with the academic qualifications and technical expertise to conduct one, or more, of the following activities;

The surveyor’s professional tasks may involve one or more of the following activities which may occur either on, above or below the surface of the land or the sea and may be carried out in association with other professionals.

Ghana, south coast

Costa Rica Declaration on Pro-Poor Coastal Zone Management

Published in English

Published by The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

ISBN: 978-87-90907-66-2, June 2008, Copenhagen, Denmark

Printed copies can be ordered from:

FIG Office, Kalvebod Brygge 31-33, DK-1780 Copenhagen V, DENMARK,

Tel: + 45 38 86 10 81, E-mail:

[email protected]